Introduction

With an average economic growth over 6% in the past two decades, Bangladesh has emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies of the new millennium (IMF, 2020). It crossed the World Bank’s lower middle-income country threshold in 2015 and met the eligibility criteria for graduation from the United Nation’s Least Developed Countries (LDC) list in 2018. Sustained economic growth has led to a marked decline in poverty rates, from 44% in 1991 to 18% in 2022 (AsaduzZaman & Byron, 2023; World Bank, 2018). One of the world’s poorest countries on independence from Pakistan in 1971, Bangladesh saw its economy grow almost 50 times by 2021, to US$416 billion. It surpassed Pakistan’s per capita income in 2015 and India’s in 2020 (The Financial Express, 2021).

Bangladesh has focused on an export-led economic growth model and become a leader in the textile industry. A resource-poor nation of 170 million with few mineral resources except for natural gas, it is one of the most densely-populated countries in the world, with nearly 1,300 people per square kilometer (World Bank, 2020a). Despite significant recent strides, Bangladesh’s educational attainment remains low, with only 63% of the population over 25 completing primary education, 22% secondary education, and 9% tertiary education (World Bank, 2020b). Its large and relatively unskilled population, coupled with a very high population density and lack of natural resources, make its achievements especially notable.

We analyze the lessons that Bangladesh’s sustained economic growth and development have for policymakers and generate insights for managers of multinational corporations (MNCs) on how they can operate effectively in this rapidly-growing, but challenging, emerging market. We discuss policy ideas with both government and practitioner perspectives that provide multiple opportunities for businesses to work with policymakers for mutual benefit. These include a focus on moving up the global value chain (GVC), engaging with the diaspora, improving physical and regulatory infrastructures, and leveraging non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for inclusive value creation.

Reasons Behind This Transformation

Bangladesh’s export-led growth model is a major factor behind its rapid economic growth and development. Its industrial policy focuses on labor-intensive light manufacturing, facilitating integrations into the lower end of global textile value chains while generating employment for its large population. It is currently the second-largest garments exporter, after China. Over 80% of its exports are readymade garments. Other major export items include fish, shrimp, leather, and jute products (Seric, 2022).

In addition to its export-led growth model, Bangladesh focused on the human development of its large population. Consistent with the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[1], reductions in infant mortality and childhood malnutrition (with corresponding increases in life expectancy and educational attainment), and a focus on women’s empowerment, led to large increases in its ranking on the human development index (HDI), from 0.49 in 2000 to 0.66 by 2022 (Ali, 2022). NGOs were instrumental in this transformation and have been at the forefront of development efforts in Bangladesh. This includes two of the world’s largest NGOs: BRAC (formerly Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee) and Grameen Bank. Their efforts have included poverty alleviation, education, healthcare, microfinance, and women’s empowerment. Successive governments have emphasized the role of NGOs in development and encouraged their social innovations involving stakeholders from the base of the pyramid (BOP). This has often led to locally-sourced frugal innovation as a solution for complex challenges – one example being microfinance lending pioneered by Grameen Bank. Social enterprises facilitated by NGOs and grounded in local communities helped people at the BOP to engage in productive livelihoods. Nearly 70% of workers in the garments sector are female, highlighting its role in empowering women and the interconnectedness of these developments.

MNCs’ participation and commitment is also important in the achievement of the UN SDGs (Ghauri, 2022), and we see numerous cases of MNC-NGO alliances in Bangladesh that have helped achieve, simultaneously, business and development goals. Telenor, a Norwegian MNC, collaborated with Grameen Telcom (a sister company of Grameen Bank), and helped design a new business model for underprivileged villagers. They established the Village Phone (VP) program, enabling villagers, mostly women, to buy a cell phone with small loan packages provided by Grameen Bank. This partnership helped create social legitimacy for Telenor. Similarly, Novo-Nordisk entered a strategic alliance with the Diabetic Association of Bangladesh (BADAS) to sell insulin products to patients through BADAS networks (Lalzai, 2020). HSBC Bangladesh worked with TMSS (Thengamara Mohila Sabuj Sangha), a local microfinance NGO that focuses on women to alleviate poverty, providing social loans to 30,000 microentrepreneurs. The loans were used to generate employment and provide access to healthcare, while simultaneously helping HSBC to enhance its sustainability and support in the community (HSBC, 2022).

Bangladesh’s development efforts have been further facilitated by its diaspora, one of the world’s largest at over 10 million. Diaspora remittances totaled nearly US$22 billion in 2022, the seventh highest in the world (The Daily Star, 2022). While most remittances are used to support consumption, up to a third are used for investment, mostly in real estate (ILO, 2014). In addition, transnational diaspora networks help transfer knowledge, skills, and facilitate institution-building.

Bangladesh was one of the few countries whose economy grew during the COVID-19 pandemic. The government has plans for Bangladesh to become one of the 25 largest global economies by 2030 and a high-income country by 2041 (The Financial Express, 2021). While optimistic, at current growth rates, these targets seem achievable.

Major Challenges That Remain

While these achievements are impressive, Bangladesh remains a poor country. Despite rapid economic growth, its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita remains below US$2,700 (about US$7,400 at purchasing power parity) (World Bank, 2022). Its focus on a narrow range of low-value garments production reflects a lack of diversification in the economy. Productivity growth has been slow, with economic growth largely driven by rising investments. Despite increasing garments exports, there is little evidence of moving up the GVC. The lack of backward linkage in the industry keeps value addition low. Physical infrastructure bottlenecks also hamper economic growth.

Institutional weaknesses and lack of transparency are problematic, and corruption remains a serious issue. This is especially concerning given that SDG 16, which includes targets on reducing bribery, strengthening institutions, and bolstering anti-corruption mechanisms, is considered instrumental for the achievement of all 17 SDGs (UNDP, 2020). Bangladesh’s rank of 147 (of 180) in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (2022) is particularly worrisome. Multiple local surveys have reported that businesses are seriously hampered by corruption, lack of transparency, and a cumbersome bureaucracy. This makes doing business difficult, as noted by the World Bank’s (2019) Ease of Doing Business ranking of Bangladesh at 168 of 190 countries, ahead only of Afghanistan in South Asia. According to the Center for Policy Dialogue, an independent local think tank, Bangladesh’s improvements in economic and social outcomes have not been matched by institutional development, with its institutions ranking among the lowest in the world. This was also reflected in its ‘Mostly Unfree’ ranking by the Heritage Foundation’s (2023) Index of Economic Freedom, at 123 of 176 countries, with particularly low scores in judicial effectiveness and government integrity.

A highly dysfunctional political system has led to frequent bouts of political violence and prevented the emergence of a national consensus on development. Accusations of democratic backsliding against the current government (which has been in power since 2009), and political uncertainty (with the main opposition boycotting national elections held in January 2024), have further eroded public trust in the political system. High global inflation, supply chain disruptions, and shrinking foreign currency reserves remain causes for concern. This has led to a devaluation of the Taka and higher domestic inflation.

Recommendations for Policymakers and MNCs

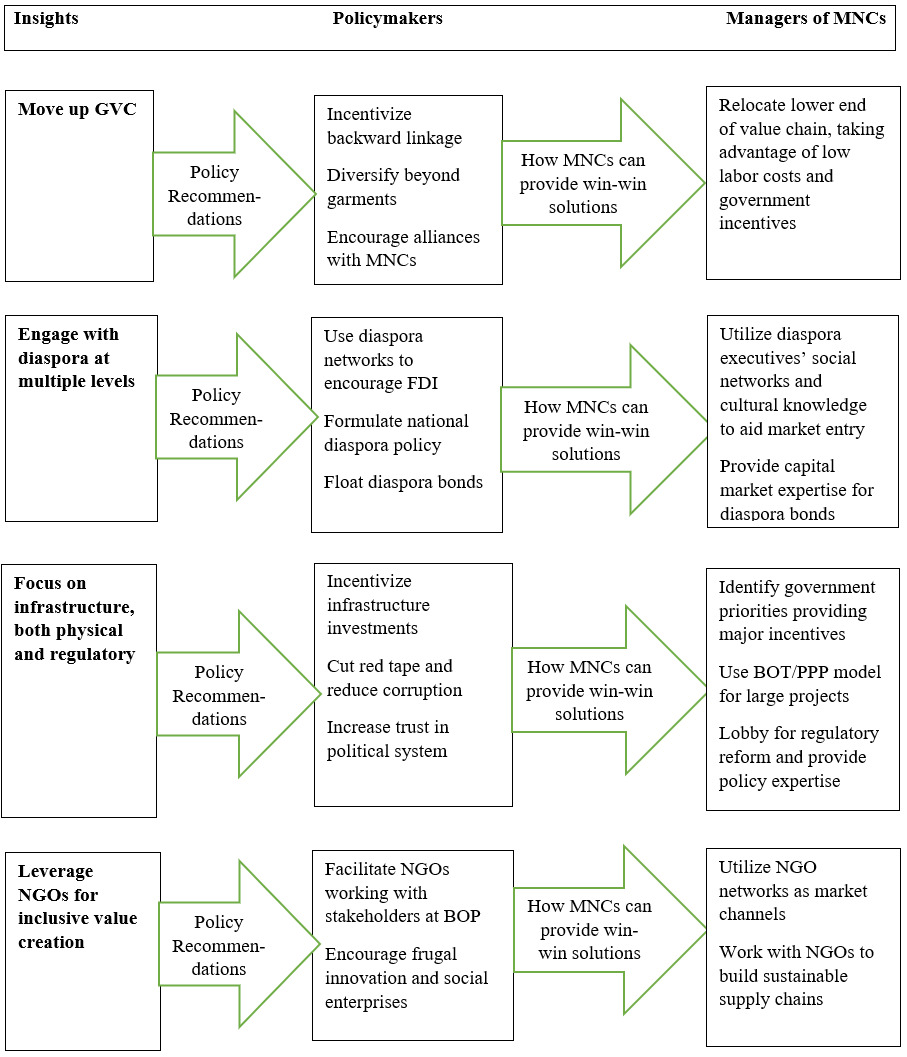

We summarize our four key actionable insights for policymakers and managers of MNCs in Figure 1. Each insight includes recommendations for policymakers as well as opportunities for MNCs to work with them to create win-win solutions.

Focus on Moving up the GVC

This will mean emphasizing factor productivity growth and upskilling of employees. MNCs whose operations facilitate backward linkages in the apparel industry would be well-placed to capture a greater share of the GVC. Combined with the low-cost labor force, this realignment could enhance in-house value creation. It would also align with the government’s industrial policy and thus be eligible for investment incentives. Current incentives for MNCs in designated economic zones that help with backward linkage include up to 100% income tax exemption for the first 10 years.

Policymakers should also encourage diversification into other GVCs, to reduce dependency on a single industry. Possible areas for diversification are fisheries, shrimp, leather, jute, and information technology (IT). MNCs in these industries can work with local partners to avail low labor costs and favorable government regulations, initially by offshoring low value-adding parts of their GVCs to Bangladesh. Current government regulations in the IT sector, for example, include a 10% cash incentive for exports.

Engage with the Diaspora at Multiple Levels

Bangladesh is in the process of formulating its first national diaspora policy, which aims to strengthen support for business development to encourage foreign investment. This provides an opportunity for MNCs to engage with the diaspora, to facilitate entry into the Bangladeshi market. Diaspora members can provide businesses with local cultural and market knowledge, while their transnational social networks can facilitate trade, investment, and trust building. Diaspora-facilitated investments can provide further insights on succeeding in this challenging market.

Diaspora bonds targeted at affluent members can be important in mobilizing them for national development in a mutually-beneficial relationship. These bonds could help raise funds for large infrastructure projects and create resilience in foreign currency reserves. Financial services MNCs can engage the government with expert advice and bond underwriting, while simultaneously growing their market presence.

Focus on Infrastructure, Both Physical and Regulatory

Recently, the government has invested heavily in physical infrastructure. Some of the multibillion-dollar projects completed in the last five years include the Padma bridge (connecting the southwest to the northern and eastern regions of the country), the Dhaka metro rail (an urban mass rapid transit system), and the Dhaka elevated expressway (designed to ease traffic congestion). There are incentives available for MNCs to invest in similar large infrastructure projects, as well as opportunities for public-private partnerships (PPPs). Current incentives include up to 100% income tax holiday, exemptions in capital gains tax, and 100% repatriation of profits and dividends for the first 10 years. MNCs can work with the government to invest in infrastructure development, utilizing current incentives and taking advantage of Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) models. It would be helpful for MNCs to involve their home government agencies in these negotiations, to obtain favorable terms.

Increasing trust in the sometimes-dysfunctional political system will be vital and will require the creation and strengthening of independent and impartial institutions. Regulatory efficiency, in terms of reducing corruption, increasing the ease of doing business, and improving government services, is essential for attracting more large-scale investment. MNCs can help improve policy decisions by providing information and policy expertise about regulations in other countries when called upon, thus positively affecting regulatory efficiency.

Leverage NGOs for Inclusive Value Creation

NGOs can be valuable partners for sustainable economic growth. It is especially important to involve stakeholders at the BOP and encourage locally-sourced frugal innovation and social enterprises to help with achieving SDGs. MNCs can benefit from NGOs’ networks that can act as market channels (e.g., in slums and rural areas) as well as gaining social legitimacy from collaborating with them. Telenor and Novo Nordisk are good examples of how this is potentially a win-win solution. The movement to work with NGOs on issues of mutual concern is a worldwide phenomenon and encompasses making global supply chains more sustainable. MNCs such as Apple, Dell, H&M, IKEA, and Microsoft collaborate with NGOs, worldwide, to promote sustainable global supply chains (Heugens & Liu, 2021). This facilitates the empowerment of subordinated value chain stakeholders that is essential for inclusive GVC governance, such as the Bangladesh Accords, which protect worker safety and had numerous NGO signatories (Wang et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Bangladesh’s sustained economic growth and strides in human development over the past two decades provide important insights for policymakers in emerging and frontier economies, who can take lessons about the importance of targeted industrial policy and developing human capital in line with the UN’s SDGs. Bangladesh provides a good example of how a country that is densely populated, natural resource poor, and with a relatively unskilled population, can identify a key industry (in this case garments) and integrate itself into the lower end of GVCs for sustained economic development. Another key insight is the importance of engaging with development partners such as NGOs. In Bangladesh’s case, this has helped to involve the population at the BOP to share the benefits of growth, and encouraged frugal innovation. Leveraging the diaspora, both for remittances and domestic capacity building, has also proven to be vital. Having an integrated national diaspora policy with involvement from multiple stakeholders should further strengthen this relationship. Developing countries with large diasporas could benefit both from studying Bangladesh’s example, as well as the challenges it still faces in this regard.

We also generate insights for MNCs. Bangladesh’s rapid economic growth and large population make it important for foreign businesses, as both a consumer market and a low-cost manufacturing hub. MNCs can benefit from utilizing government incentives aimed at creating backward linkages to facilitate moving up the GVC and capture more of the value chain. Participating in high-priority infrastructure projects, particularly through BOT and PPP models, can generate long-term returns and facilitate market access. Providing the government with regulatory expertise and creating long-term partnerships focusing on the growing consumer market (possibly with the help of NGOs) can help generate social legitimacy. MNCs could also benefit from engaging with the diaspora, who have cultural competence and transnational social networks.

These recommendations can provide opportunities for both businesses and policymakers to engage in win-win solutions; both sides should view this as an opportunity to further enhance their cooperation in pursuit of shared objectives. Future work can develop more detailed solutions for the challenges faced by Bangladesh, and other similarly-situated economies, and consider how local firms can benefit from its sustained economic growth and development.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their help and guidance in developing this manuscript.

About the Author

Masud Chand is a Professor of International Business at the W. Frank Barton School of Business at Wichita State University. His research interests include the role of immigration and diasporas in driving cross-border trade and investment and the aging of populations and its effects on the global business environment. His work has been published in numerous journals including the Academy of Management Perspectives, International Business Review, Journal of Business Ethics, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, and the Journal of International Business Policy.

Their precursors were the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs).