Introduction

Social movements have long played a pivotal role in shaping the civic and business environments of multinational enterprises (MNEs) (King & Pearce, 2010). These movements appear with a wide range of structures, beliefs, and goals (Passarelli & Tabellini, 2017). Despite these variations, they are tied by some common threads. While research has focused on the political and social dimensions of social movements (Amenta, Caren, Chiarello, & Su, 2010; Raskovic, 2020), there is still a limited understanding of the economic ramifications, particularly in scenarios where MNEs need to adjust from their initial position and respond to the social movement.

The 2019 social movement in Hong Kong was a multi-faceted phenomenon (Lee, 2020) in which social movement organizations such as the Civil Human Rights Front, Demosisto, and the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions were at the forefront of mobilizing citizens to raise their voices (Ma & Cheng, 2021). Amidst the complex interplay of social movement organizations with varied objectives and strategies, MNEs in Hong Kong grappled with a constantly evolving socio-economic environment. They faced disruptions on multiple fronts, including operational, reputational, and financial challenges. The call for greater political autonomy posed a unique challenge for MNEs, as it intersected with their business operations, requiring them to navigate a delicate balance between local political sentiments and global business interests. Understanding the significance of social movements that have the potential to disrupt economies is, therefore, crucial for MNEs (King, 2008). Recognizing the interplay of social, political, and economic factors in today’s world, MNEs must navigate disruptions while considering their economic and political implications (Dau, Moore, & Newburry, 2023).

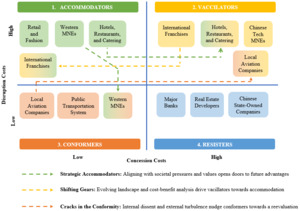

Extending the economic opportunity structure (EOS) framework proposed by Luders (2006), we investigated the strategies – and possible shifts in those strategies – used by MNEs during the 2019 Hong Kong social movement. In the EOS framework, MNEs employ distinct strategies to respond to social movements. Accommodators prioritize swift recovery through concessions, showcasing a nuanced understanding of disruptions and a willingness to absorb costs for prompt business continuity. Vacillators balance high disruption and concession costs, which demands strategic agility to navigate the challenges posed by social movements. Conformers align with local sentiment, incurring concession costs while minimizing disruption. Resisters oppose social movements, bearing high concession costs and prioritizing principles over immediate economic considerations. However, MNEs may move between these categories in response to the evolving situation.

Luders’ framework, originally designed for organizations operating within their home country, also gains new dimensions when we consider the challenges faced by MNEs operating internationally. By integrating insights from international business theories, such as the liabilities of foreignness and outsidership, we extended Luders’ framework to a more international context. This enriched framework offers a clearer picture of how MNEs navigate the complexities of social movements in different regions. Zaheer’s (1995) research on overcoming the liability of foreignness sheds light on how MNEs can address the specific challenges of operating in unfamiliar environments. For instance, MNEs might consider building trust with local stakeholders through culturally sensitive communication and community engagement practices. This aligns with Luders’ engagement and co-optation strategies. Johanson and Vahlne’s (2015) revised Uppsala model moved beyond the concept of “liability of foreignness” to “liability of outsidership,” emphasizing the ongoing challenges MNEs faced even after establishing a presence in a new market. MNEs might encounter resistance due to their foreign origins or lack of deep understanding of local norms. This aligns with Luders’ strategies of adaptation and deflection, through which MNEs adjust their practices or deflect criticism by emphasizing positive contributions.

Extending Luders’ framework, our study explored the motives shaping MNEs’ responses to social movements, and the shifts they might make from their initial response types. Our findings reflect a detailed exploration of how a social movement challenges firms in complex and nuanced ways, and provide actionable insights for MNEs.

Extending the EOS Framework to International Businesses in Hong Kong

MNE Responses to the Social Movement

The 2019 Hong Kong social movement disrupted both local and international businesses, leading to a distinct divide between those supporting the movement symbolically or under stakeholder external pressures, and those who opposed it (often for similar reasons). Despite facing similar economic disruption, MNEs responded differently. A subset of businesses adapted their strategies in response to escalating local violence and external tensions, particularly from mainland China (Fiedler, Tsang, & Reichert, 2022). This case highlighted the fact that corporate responses to social movements are not solely dictated by economic disruption, but are also shaped by nuanced contextual factors (e.g., dominant logic(s)).

MNE Initial Responses

Figure 1 presents an overview of the initial responses to the social movement of MNEs in various industries in Hong Kong. This breakdown is crucial because different industries and sectors face varying levels of scrutiny from external stakeholders and potential disruption from social movements. We refined Luders’ EOS framework, therefore, by considering the source or origin of disruption and concession costs: local, mainland China, and global. This additional layer helps explain the different behaviors and responses of MNEs compared to local businesses facing the impact of the same social movement.

Accommodators. MNEs in the hotel, restaurant, and catering industry – particularly international hotels and restaurant chains – faced high disruption costs during the movement. The retail and fashion industry faced a similar level of disruption. These costs included lost revenue, damaged property, and reputational harm. Accommodators, according to EOS, prioritize minimizing disruption. Foreign MNEs, as outsiders, likely felt pressure to avoid taking sides in a local political conflict, particularly when their dominant logic did not align with the local sentiment. Outsidership – the ongoing challenges of operating in a new market even after establishing a presence – also influenced their approach. They strategically downplayed the disruptions and refrained from taking a clear ideological stance, focusing instead on restoring normal economic activity. This approach aimed to minimize negative impacts and maintain neutrality, which is crucial for businesses reliant on tourism and local customers. Examples include Taiwanese tea companies strategically downplaying mainland consumer boycotts. As the movement progressed, many MNEs continued to minimize disruption without actively promoting the movement.

Vacillators. These actors struggle to choose between supporting or opposing a movement due to uncertainty about what the effect might be on their business. Chinese technology MNEs faced significant economic losses due to a perceived association with the Chinese government but, despite this, some exhibited characteristics more aligned with vacillators than accommodators. They did not entirely abandon their usual operations but actively sought alternative solutions, highlighting the challenges of outsidership.

Conformers. These actors prioritize aligning with the dominant narrative to avoid negative consequences. MNEs in this category aim to conform not only to local pressures but also potentially to the dominant logic in mainland China (a crucial market) and the broader global market. This balancing act can lead to more nuanced conformist behavior compared to local businesses solely focused on local sentiment and context. Western MNEs, initially exhibiting an accommodator stance, faced pressure from mainland China due to their public expressions of sympathy for the movement. Foreignness again came into play. These companies relied heavily on the Chinese market, making them vulnerable to pressure from Chinese consumers and the Chinese government. This case deviates from the traditional conformer pattern due to the significantly different dominant logic and narratives in Hong Kong and mainland China. Western MNEs prioritized conforming to China, reflecting the distinct socio-political dynamics and consumer sentiments of that region. This highlights how outsidership can influence decision-making. Western firms, even the very established ones, might prioritize conforming to the dominant narrative of a powerful host country to maintain access to a vital market.

Resisters. Resisters prioritize their values and interests even if it leads to economic losses. Chinese state-owned companies that made unequivocal calls for a peaceful resolution from the outset can be categorized as resisters. They remained unsupportive of the movement, potentially prioritizing core values and alignment with the Chinese government over short-term economic gains. While this strategy preserved their core interests, it likely contributed to ongoing challenges in the complex socio-economic landscape. Similarly, major banks and local real estate developers, while recognizing the potential cost of disruption, consciously chose not to align with either side. This approach was not merely about preserving neutrality; it was a calculated decision to resist being co-opted into the controversy. By doing so, they subtly resisted the pressures of the movement, maintaining a stance of cautious detachment in the face of uncertainty.

MNE Stay and Migration Strategies

As the social movement in Hong Kong unfolded, some MNEs changed their initial stances (see Figure 1). This reflects Johanson and Vahlne’s (2015) Uppsala model in that MNEs do not have perfect information and must adapt as they learn more. MNEs could choose to stay and adapt their initial response type within Luders’ framework or migrate entirely to a different category of response based on changing circumstances and pressures. For instance, accommodators might prioritize minimizing local disruption costs while potentially accepting some concession costs in mainland China or the global market. MNEs might decide to migrate to a different category based on the changing landscape of disruption costs. Likewise, an MNE initially adopting a conformer stance might shift towards an accommodator stance if the social movement intensifies and local disruption costs become more significant.

Migration from accommodators to conformers. Western MNEs initially acted as strategic accommodators, prioritizing minimizing disruption in Hong Kong. However, unforeseen challenges emerged, such as boycotts from mainland Chinese consumers and pressure from stakeholders with ties to China. For example, Google was asked a few times to remove apps that were believed to threaten national security in Hong Kong. Activision Blizzard suspended the player Chung Ng Wai (known as “Blitzchung”) from the professional league for a year after he articulated his support for the Hong Kong movements in a live broadcast. Luders’ framework is particularly relevant here. As foreign MNEs, both companies were susceptible to pressures that could affect their ability to navigate the socio-political landscape (i.e., the liability of foreignness). To mitigate these disruption costs, MNEs migrated towards a conformer stance. This shift involved issuing public statements aligned with the Chinese government or reducing operations in Hong Kong. This case exemplifies the complex cost calculations MNEs must make, where potential losses in a major market can outweigh disruption costs from a social movement elsewhere.

Migration from conformers to vacillators. Dominating the regional aviation market, Cathay Pacific initially adopted a conformer stance by avoiding condemnation of employee participation in the movement. This aligns with the EOS framework in that an accommodation strategy may minimize disruption costs. However, facing harsh government responses and online scrutiny (i.e., rising concession costs), Cathay found it difficult to maintain this stance. New regulations and employee dismissals pushed them toward a state of vacillation. Luders’ framework helps dissect these cost pressures and Cathay’s strategic maneuvering in this situation.

Migration from vacillators to accommodators. Maxim’s Business Group initially adopted a vacillating stance due to uncertainties around the movement impact on business operations. There was a sense of acute anger from both Hong Kong and the mainland oriented toward the Business Group, which owns and operates Starbucks Hong Kong and many other US franchises (Craymer & Haddon, 2019). Consistent with Johanson and Vahlne’s (2015) Uppsala model, Maxim’s initially exhibited a measured approach, recognizing the potentially high costs of concessions and disruptions inherent in their potential expansion in the Chinese market However, the business group later moved to a fully accommodative strategy. This proactive shift prioritized long-term sustainability and sheds light on the strategic interplay between disruption and concession costs.

Stay strategy. The Mass Transit Railway Corporation (MTRC), the biggest player in Hong Kong public transport with a global presence, adopted a stay strategy. MTRC remained a conformer throughout. Despite disruptions, they continued their operations because their services were indispensable (i.e., low disruption costs). Their focus on the local market also minimized concession costs. This strategy aligns with the EOS framework, reflecting an accommodation strategy focused on maintaining a low profile and minimizing disruption. Likewise, major real estate developers with operations across multiple countries adopted a similar strategy. They collectively issued a statement condemning the actions of the movement and calling for stability. This was a coordinated stance among prominent MNEs designed to maintain order and resist being swept into the fray. Several examples of the initial positions and migration strategies of MNEs are summarized in Table 1, which also shows the timing and rationales behind these choices.

Actionable Insights

The 2019 Hong Kong social movement highlighted the complex challenges faced by MNEs during social unrest. The EOS framework initially classifies organizations’ responses into four categories: accommodators, vacillators, conformers, and resisters. This helps us understand how MNEs navigate the interplay between the disruption and concession costs associated with social movements. However, it is also crucial to recognize the importance of positioning and segmentation, flexibility and adaptability, and association management.

Beyond their initial categorization, MNEs should consider tailoring their responses through positioning and segmentation. For instance, an MNE operating in both Hong Kong and mainland China might need to adapt its stance based on the specific political climate and sentiment in each region. Similarly, segmenting stakeholders allows MNEs to understand diverse viewpoints (employees, customers, investors) and craft targeted communication strategies. MNEs that thrive in uncertain environments demonstrate a high degree of flexibility and strategic agility. This allows them to adapt their initial stances within the EOS framework as the social movement unfolds. For example, an MNE might initially minimize disruption by adopting an accommodator stance but shift towards conforming to the dominant narrative if faced with widespread boycotts. This highlights the importance of constant evaluation and adaptation based on the evolving situation.

MNEs can further mitigate risk through proactive association management. This involves communicating their values and stance on issues related to the social movement to avoid negative associations. In some cases, distancing themselves from specific government entities or organizations associated with the movement might be necessary. By incorporating these considerations, the EOS framework helps explain not only the initial responses of MNEs but also their strategies for adaptation, proactive mitigation, and targeted communication. A summary of the actionable insights is presented in Table 2.

Conclusions

We extended the EOS framework by highlighting that businesses can shift their positions to effectively manage the disruption costs resulting from internal and external pressures, and the concession costs arising from aligning with societal expectations. Our research helps practitioners better understand how MNEs strategically manage their responses when facing social movements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editors and reviewers for their insightful comments and guidance throughout the revision process.

About the Authors

Aureliu Sindila is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Business, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong. His research interests are centered on the topics of organizational resilience, crisis management, repugnant transactions, time in management and organizations.

Xueyong Zhan is an associate professor in the Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Business, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong. He received his Ph.D. in public administration from the University of Southern California. His research examines business sustainability and public policy, philanthropy and nonprofits, and public management.