Some tools of reasoning illuminate some aspects of the phenomena to be studied, but others actually cloud that understanding and steer our mental focus in other directions. – Peter J. Boettke

Introduction

Firms often face complex challenges that would benefit from actionable insights, yet the suggested scholarly remedies for advancing international business (IB) research fall short: “Study big questions” or “Enhance replicability.” Although we do these in good faith, there remains a disconnect between how international business scholars design their studies and how managers and their firms think. Indeed, evidence suggests that even if we tout our conversations (and findings) as meaningful, firms do not behave any differently (e.g., Ferns & Amaeshi, 2021). This is a complicated issue, and leveraging existing methodological approaches can arguably help address some of the problems (Eden & Nielsen, 2020). Nevertheless, we argue that there is room for improvement in how we approach our research to enhance its rigor and relevance, especially in addressing contemporary issues.

These notions are not new. Recently, there has been considerable pressure to cast a critical and discerning eye on the design of IB research (Delios, Welch, Nielsen, Aguinis, & Brewster, 2023). The IB community has become increasingly aware of the need to transition into a “new era” of empirical precision and responsibility. That is to say, our research practices are under review to identify areas for improvement in conducting, reporting, and archiving. Ensuring this progress is a difficult task. Like any change, it involves raising awareness of our current models’ limitations and allowing new ones to emerge. At a minimum, embracing new ideas and methodologies can help ensure IB research keeps pace with adjacent disciplines.

This paper lays the groundwork for incorporating necessity-based research to advance international business scholarship. It is a complementary conceptual and empirical apparatus for designing research that inherently resonates with managers and the firms they lead. While necessity-based research is not a silver bullet, it offers a different way to consider relationships between cause and effect. It considers the extent to which membership of an organization in a cause is associated with its membership in an effect (Fainshmidt, Witt, Aguilera, & Verbeke, 2020; Furnari et al., 2021). If scientifically sound findings are less impactful if they have minimal practical application, then we argue that necessity-based research can help push the boundaries in this regard, providing novel insights into the complexities of IB phenomena and equipping firms with actionable insights.

Thinking in necessity terms has implications for the whole gamut of research activities, from formulating research questions to developing theoretical arguments and executing empirical analyses. The following sections consider these key aspects, illustrating its potential to refine our understanding of multinational firms and its implications for theory and research. We use the example of multinational firms seeking to improve environmental performance as an illustration. While our discussion may not provide a comprehensive roadmap (cf. Dul, 2016; Richter & Hauff, 2022), it is designed to stimulate a conversation among IB scholars interested in conducting top-level academic research that resonates with firms and contributes to the field’s evolution.

In Degree and Combination

International business research is not designed to guarantee outcomes; in other words, no single condition is theorized to be sufficient. Aiming to do so would be unrealistic when studying complex phenomena such as IB. However, a condition can be a necessary cause that allows an outcome to exist. In other words, necessary conditions act as a constraint or barrier, so to speak, that must be managed; if the first condition had not occurred, the second would never have existed.

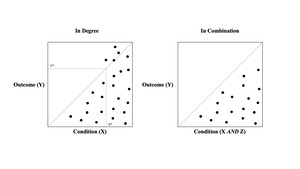

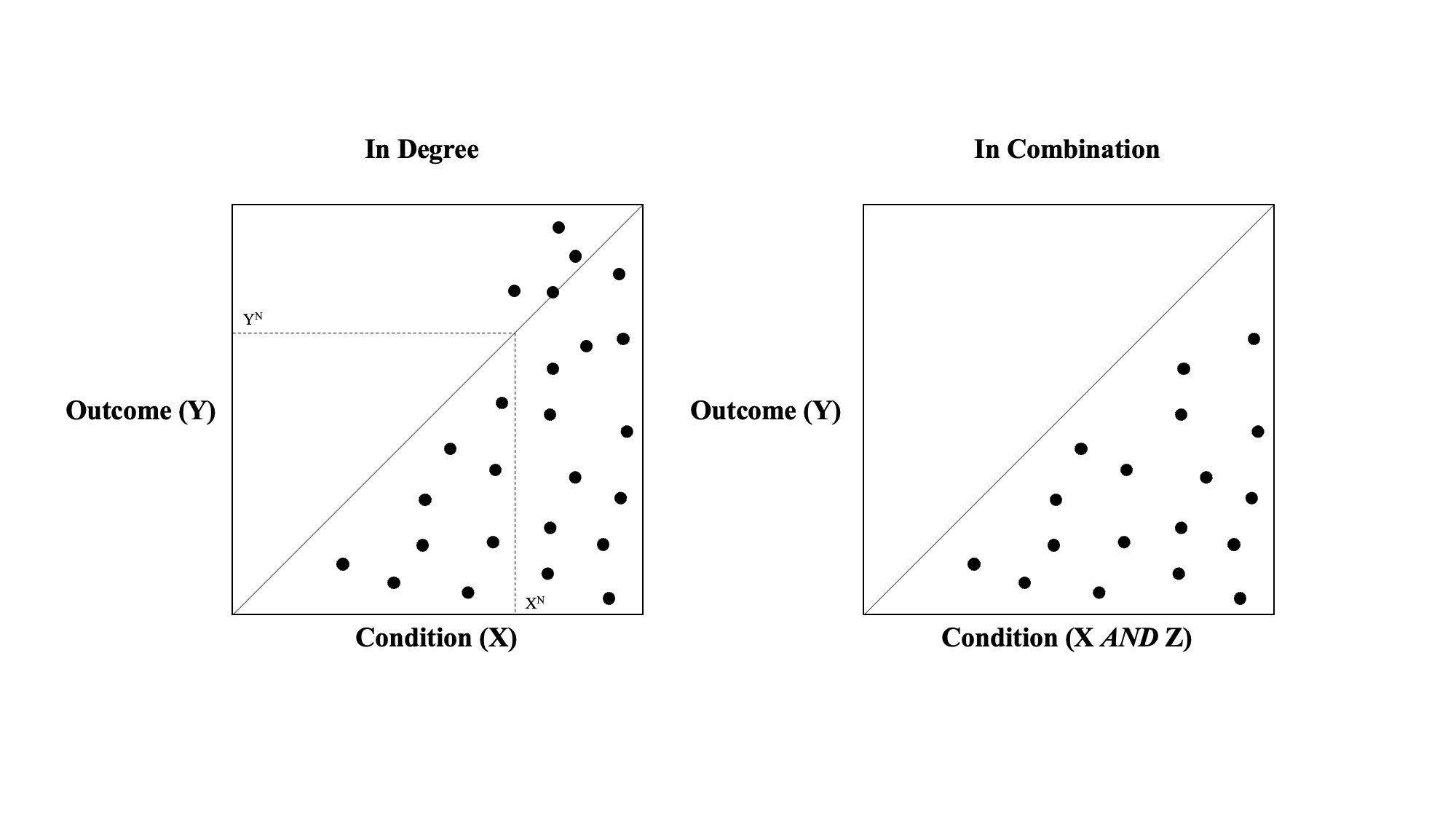

To incorporate necessity-based thinking, IB scholars can conceptualize necessary conditions in at least two ways: in degree and in combination. Figure 1 illustrates these distinctions. The first is to formulate a quantitative in degree statement. For these statements, scholars can formulate questions such as: “How much should a multinational firm invest to make a positive environmental impact locally?” On the left side of the Figure, the ceiling line for environmental performance (YN) represents all possible values of green investments (XN) where these investments are necessary for environmental performance. Algebraically, this suggests that level X ≥ XN of condition X is necessary for level YN of outcome Y. More simply, this approach helps determine the necessary levels of a condition (e.g., green investments) for a specific level of an outcome (e.g., environmental performance), recognizing that the condition may or may not be necessary depending on the desired outcome level.

The second related formulation focuses on necessary conditions in combination. When considering such statements, scholars focus on sets of conditions joined together by the logical operator AND. Unlike in degree formulations, the conditions are necessary together for the outcome to occur. Continuing the example, a multinational firm’s green investments AND political investments, such as lobbying host country bureaucrats seeking to impose new regulations, may be necessary together to mitigate stakeholders’ environmental concerns or improve environmental performance. All combinations of conditions must be on or below the diagonal line (right side of the Figure), implying that both investments are necessary underlying conditions.

Importantly, necessity can be applied to conditions and outcomes measured in different ways (Richter & Hauff, 2022). In the simplest form, a dichotomous condition is either necessary or not for an outcome, such as the presence of X being necessary for the presence of Y. More complex necessity statements specify that certain levels of a condition are required for certain levels of an outcome, as shown by our examples where different levels of, for instance, green investments are necessary for different levels of environmental performance, illustrated by empty spaces in the upper left corners of the scatter plots (Figure 1). Additionally, while there may be multiple necessary causes for an outcome, the necessity of each cause is evaluated independently or in combination, without influence from other determinants.

We make two additional points. First, as some conditions can be continuous, IB scholars may define various sets from the same variable. For instance, “medium” or “very high” green investments are distinct sets and may affect environmental performance differently. It could be that investing over a certain threshold has no additive effect and may even hurt environmental performance. Second, researchers can conduct necessity analysis on variables without converting them to sets or causal conditions. Below, we discuss advances in empirical techniques that make this possible.

A Necessary (But Not Sufficient) Path Forward

Incorporating in degree or in combination thinking into IB research requires a systematic approach that spans the entire research process. Inherent are fundamental changes in how we design research questions, develop theory, and draw implications. Such necessity-based thinking can be particularly valuable in addressing some of the challenges specific to IB. For instance, it can help tackle the interdisciplinary nature of environmental performance by providing a framework to test and refine explanations from multiple disciplines. It can also assist in contextualizing insights, as necessary conditions may vary across different countries, cultures, or institutional environments. Hence, we provide a path forward for those interested in integrating necessity-based thinking into their future works.

At the onset is the design of research questions and the potential for incorporating necessary relationships between conditions and outcomes. This involves moving beyond simple cause-and-effect and instead thinking about the necessary conditions for a desired outcome to occur (see Greckhamer, Furnari, Fiss, & Aguilera, 2018). Traditionally, the typical IB study would ask, “Do green investments improve a multinational firm’s environmental performance?” Implicit in the analysis, albeit seldom acknowledged in IB, is that an answer to such a question will indicate “on average” effects. However, a necessity frame is different: “What level of green investments is necessary for a multinational firm to achieve a specific level of environmental performance?” or “What combination of green investments and other conditions is necessary for a multinational firm to mitigate stakeholder concerns?” Focusing on specific thresholds, the revised questions move beyond general, average effects to advance a more novel understanding of the conditions (and their levels) necessary for successful green investments. Table 1 illustrates how future IB research can adapt research questions to incorporate necessity. We focus on the multiplicity of actors, multiplexity of interactions, and dynamism of systems (Eden & Nielsen, 2020).

Once research questions have been formulated, the next step is to connect them to existing theories and identify necessary conditions. Like traditional studies, this involves reviewing the literature to identify those conditions that have been shown to influence the outcome of interest. However, necessity-based thinking diverges as it inherently considers how conditions may vary in degree and in combination to create necessary conditions. In the green investment example, a study might draw on stakeholder theory to identify the key stakeholders (e.g., local communities, NGOs, governments) whose concerns must be addressed and on institutional theory to consider how regulatory pressures (e.g., reporting, emissions testing, carbon offsetting) may create necessary conditions for environmental performance. Identifying these conditions and how they vary lays the groundwork for selecting appropriate data collection and analysis methods.

Concerning data collection and analysis, scholars should select methods well-suited to examining necessary relationships. Among IB research, there is a growing recognition of neo-configurational methods—or the analytical appreciation that “organizational choices, practices, and performance indicators derive from complex interactions among interrelated parameters” (Fainshmidt et al., 2020: 456)—that emphasize the importance of necessary and sufficient conditions. This includes Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) or Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012).[1] These methods allow for the identification of conditions that must be present for an outcome to occur and the exploration of how these conditions combine to create necessity. In the environmental performance example, a study might include data on the level of green investments made by multinational firms, as well as on other conditions such as stakeholder pressures, regulatory requirements, and firm characteristics. It could then use NCA, QCA, or another appropriate methodology to identify the combinations of conditions necessary for firms to achieve a specific level of environmental performance. Note that a condition’s level does not have to be “high,” depending on the research question. For example, Van der Valk et al. (2016) use necessity-based thinking to explore the importance of contracts for supplier-led innovation in service outsourcing relationships and find that at least a medium level of detail in the supplier contract, as well as no compromise on levels of trust, is necessary.

Finally, necessity-based thinking directly informs theoretical development and the drawing of implications. By identifying the necessary conditions for an outcome, scholars can refine existing theories and develop new ones that better capture IB’s complexity (Furnari et al., 2021). Using the ongoing example, necessity-based findings might lead to a new theory that, by design, could have implications for resource-constrained firms, such as those needing to balance investments in costly initiatives to meet the necessary conditions to alleviate environmental pressures. In sum, necessity-based thinking spans the entire research process: designing research questions focused on necessity relationships, connecting these questions to existing theory, selecting appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and leveraging the findings to inform theory and derive actionable insights.

Necessity and Future Research

Our position is that necessity-based research is a building block for top-tier IB research. This is because the essence of good research involves formulating the right question and choosing the most effective method to answer that question. It sounds methodologically driven—and to be sure, many have written about methodological challenges in international business—but how we think about theory and relationships between conditions is inextricably tied to the pervasive forms of empirical inquiry. Future research needs to grapple with these issues.

As we have illustrated, there are many ways to think about necessity in IB research, and we believe its incorporation offers a valuable apparatus for advancing scholarship. Necessity can be helpful to “deconstruct complexity,” “lead to new research questions,” “build a thorough understanding,” and advance insights for external audiences (Eden & Nielsen, 2020: 1618–1619). For instance, focusing on the conditions that must be present for an outcome to occur allows scholars to refine existing theories and develop new ones that better capture the complexity of IB phenomena. This approach is particularly relevant given the contemporary landscape faced by multinational firms. As previously mentioned, incorporating necessity-based thinking moves IB theory beyond the limitations of traditional linear and additive models, often constrained to average, net effects thinking. Instead, necessity-based thinking emphasizes the importance of considering the interdependencies and interactions among conditions, as well as the potential for non-linear relationships and critical thresholds. While other methodological forms can partially achieve these issues, a necessity-based approach could also lead to complementary novel insights.

Reflecting on the environmental performance example once more, a necessity-based approach might be appropriate for developing a “necessary sustainability” theory in the context of multinational firms’ green investments and environmental performance. Such a theory would posit that firms must invest in a combination of certain initiatives across dispersed settings to achieve desirable performance. This highlights the importance of considering the interplay between firm behavior and various demands across contexts, as well as the potential for synergies and trade-offs among them. Moreover, necessity-based thinking can help IB scholars identify the boundary conditions that shape these relationships. By examining the necessary conditions for high environmental performance, future research can develop a more nuanced theory that accounts for the heterogeneity of green initiatives, critical in an era of increasing skepticism. In this way, necessity-based research can help bridge the gap between levels of analysis; it emphasizes the need to consider how broader contextual conditions enable or constrain firm actions. The upshot is that necessity can provide good explanations that simplify but avoid oversimplification.

However, although necessity-based thinking offers valuable insights, it has limitations. The term “necessity” in empirics is based on data and inferences, not to be understood too literally. Indeed, in QCA, the term “almost always necessary” is often used to describe such set relations. Drawing strong conclusions with strong words such as “necessary” is especially dangerous in the complex and dynamic IB context, where identifying truly necessary conditions can be challenging. In this way, necessity-based thinking may not always be suitable in certain international business contexts. Moreover, when studying, for instance, the early stages of multinational firms’ adoption of novel green technologies to improve environmental performance, necessity research may focus too much on what is necessary, understudying what actually gets a firm to the outcome (sufficiency) or what the effect sizes of different causes are (average net effects). This might hinder the development of a cumulative body of literature, especially nascent ones.

Nevertheless, while we admit that necessity-based thinking is not entirely novel in the social sciences, we believe it has been underutilized in IB research. As the field grapples with the challenges of complexity, incorporating necessity-based thinking into its ever-expanding toolkit can provide fresh insights that offer a pathway to top-tier research. It complements existing approaches and can contribute to a more comprehensive and realistic understanding of the multinational firm. Hence, we encourage future international business research to embrace necessity-based thinking as an important addition.

About the Authors

Daniel S. Andrews is an Assistant Professor at the Robinson College of Business, Georgia State University. His research interests include global strategy and the institutions that shape environments in which organizations compete. He received his Ph.D. from Florida International University.

Stav Fainshmidt is an Associate Professor at the College of Business, Florida International University. His research interests include the institutions and governance arrangements surrounding domestic and multinational firms and change-oriented organizational capabilities. He received his Ph.D. from Old Dominion University.

Necessity-based research is not exclusive to NCA or QCA and can be complemented by other methodological approaches to provide a more comprehensive understanding of IB phenomena. Although discussing these integrations is beyond the scope of this paper (e.g., Meuer & Rupietta, 2017), such “triangulation” can lead to more robust findings and a deeper understanding of complex issues. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this point.