Introduction

When operating in foreign markets, firms often need to tailor their strategies to better align with the preferences, cultural nuances, and regulatory requirements of the new market. Decisions such as these are heavily influenced by managers’ mental models, that is, cognitive structures that enable managers to understand, explain, and predict their environment (Niittymies & Pajunen, 2020). This has particular importance in firms’ international business (IB) operations as managers unconsciously rely on mental models formed in previous contexts, even when facing new and diverse international markets. This risk is further compounded by the fact that mental models are shaped by heuristics—cognitive shortcuts that are based on past experiences and may not accurately reflect the dynamics of different markets (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015a). Such heuristics can exacerbate the misalignment between mental models and the actual demands of international markets, leading to expensive mistakes.

The challenge is that managers do not automatically update their mental models as they accumulate experience (Niittymies, 2020). Instead, research indicates that the development of mental models is often preceded by a disruptive stimulus (e.g., Atanasiu, Ruotsalainen, & Khapova, 2022; Niittymies, 2020). Here, we refer to disruptive stimulus as an unexpected interruption that can trigger the reassessment of existing beliefs. Therefore, the question is how can managers proactively trigger their mental models to adapt to different environments, thus enabling more accurate decisions and smoother integration in unfamiliar territories.

To address this, we illustrate how disruptive stimuli influence manager’s cognitive structures, and can ultimately be used to develop mental models. Based on this understanding, we propose three practical lessons – Experience it!, Feel it!, and Repeat it! – that serve to facilitate managers in avoiding mental model misalignment and support effective integration in foreign markets.

How Disruptive Stimuli Leads to The Development of Mental Models

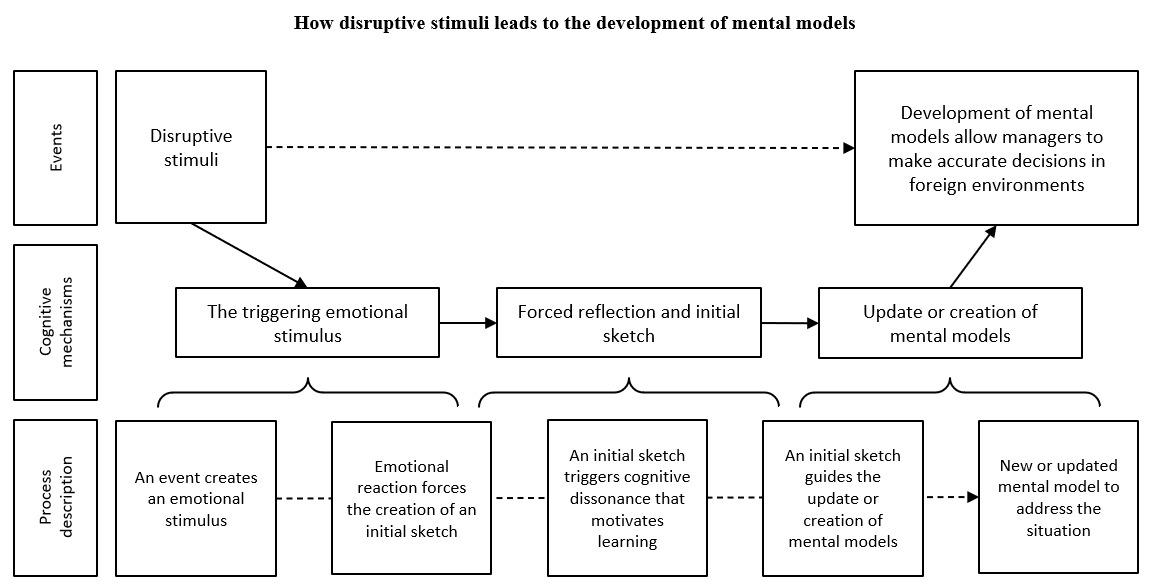

Before going into the lessons, it is necessary to understand the role of disruptive stimuli in updating mental models (see Figure 1). To explain this relationship, we focus on three interrelated cognitive mechanisms: (1) a triggering emotional stimulus igniting the learning process, (2) forced reflection and initial sketch of the problem-space that guides and motivates learning, and finally, (3) the update or creation of mental models to address the problem.

First, changing existing ways of thinking does not happen without reason. Mental model development starts with a disruptive stimulus that interrupts business as usual, forcing managers to reflect on the firm’s situation that differs from the expected or desired outcome. Mental models are cognitive structures that managers draw from when making decisions (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015a). They are built from experience, are function specific, and are used to understand their environments (e.g., Helfat & Peteraf, 2015; Kaplan, 2011; Narayanan, Zane, & Kemmerer, 2011). However, though managers may increase in experience or knowledge, this does not guarantee changes in behavior because experience does not automatically translate into mental models (Niittymies, 2020). The relationship between experience and learning is more complex. As Kahneman (2011) points out, humans seek to avoid complex cognitive tasks. This leads to continued use of existing mental models instead of spending efforts on updating them. Unfortunately, this means that firms and their managers often get stuck in their existing ways of seeing the world, which is not ideal when trying to understand different market needs (Niittymies, 2020). As Schweizer and Vahlne (2022: 587) pointed out “leaving an existing frame is extremely difficult.”

Literature on firm inertia also confirms that managers can get stuck in existing ways of thinking (e.g., Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984), especially managers with long tenure that remain grounded in outdated views of the world (e.g., Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984; Siggelkow, 2001). Hence, the assumption that managers constantly learn, without triggers or shocks, is flawed. In fact, it goes against theoretical understandings of firm inertia. In brief, the accumulation of experience alone does not update the underlying cognitive structures (Niittymies, 2020). It merely means that one has sufficient experience to update the mental models – if the required trigger is present.

Our second point relates to the initial sketch which captures what managers consider to be the most salient characteristics of the situation and is used for scanning potential courses of action (e.g., Gavetti, Levinthal, & Rivkin, 2005; Maitland & Sammartino, 2015a). The initial sketch has a critical role for two reasons. First, we note that learning is not universal but rather is tied to specific situations, problems, or tasks (e.g., Bingham & Eisenhardt, 2011; Gherardi, 1999; Maitland & Sammartino, 2015a). Therefore, managers need to draw from their experience, while considering the new context (Gavetti et al., 2005). This process enables suitable solutions to be identified from accumulated – but not used – experience. Hence, the initial sketch enables managers to create or update mental models so that a solution can be found. The second role of the initial sketch is to motivate learning. As the situation has deviated from what had been anticipated, this causes managers to experience cognitive dissonance which refers to psychological discomfort emerging when our understandings, expectations, and beliefs do not match reality (e.g., Atanasiu et al., 2022). As existing mental models offer no solution, this provides motivation to learn. In cases where the firm has experienced much success, change is more challenging as success can reinforce the trust in existing ways of thinking (e.g., Murmann & Tushman, 1997), leading to overconfidence in the capability to navigate environmental changes (e.g., Milliken, 1990), and thus, ignorance of the need to update mental models.

Finally, after the learning process is triggered, guided, and further motivated by the initial sketch, managers possess updated or new mental models that are adapted for the situation at hand. As a result, managers are better placed to make decisions concerning integration in the foreign market.

The Three Lessons

Following our explanation of the link between disruptive stimuli and development of mental models, we provide three lessons for managers to purposefully trigger and improve their mental models. These lessons aim to support managers when making decisions concerning integration into foreign or unfamiliar environments. It is important to recognize that these lessons must be contextualized according to the environment in which they are applied, especially considering the significant influence of culture. Thus, we propose these lessons as guidance on how to integrate in a foreign market, while acknowledging the importance of accommodating cultural subtleties in the local environment.

Lesson 1: Experience It! – Acquiring Experience of the Target Market

First and foremost, focus efforts on gathering experience of the target market. Experience is necessary (e.g., Maitland & Sammartino, 2015b), even if not sufficient in itself, for updating mental models (e.g., Niittymies, 2020). In addition to the usual trial-and-error approach, market research, and reports, various methods can be used to accumulate both experiential and vicarious experience (Jiang, Holburn, & Beamish, 2014). First, we suggest managers engage in rich cultural immersion experiences where they spend time living and working in the target market to learn about local culture, customs, and traditions. This can provide invaluable firsthand insights into the mindset, values, and behaviors of the target audience. If this is not viable, firms stand to benefit from recruiting a diverse team that includes experts from the relevant country to bring in the necessary experience. Second, managers should build personal networks by participating in employee exchanges, industry conferences, trade shows, and networking events within the target market. Cross-cultural exchange, interaction, and knowledge sharing with locals offer new insights, best practices, and cultural nuances leading to a deeper understanding of market dynamics. Third, we propose that managers should gather information and gain vicarious experience. For example, managers should have discussions with top management teams, local business partners, customers, and even competitors. Fourth, while the other recommendations may require more resources and commitment, with unlimited access to information afforded by technologies, managers should keep abreast of changes in the market by reading and studying about the area, its business characteristics, and its culture. This can be as simple as following the local media and public discussion to increase cultural intelligence. Based on the acquired knowledge, modern technologies also offer possibilities for small-scale pilot testing and validation of an initiative in the target market to probe for viability and acceptance. However, it is important to acknowledge that not all experiences derived from diverse environments are positive. While recognizing potential issues stemming from differences is crucial for successful management, adverse beliefs about a specific environment may impede managers’ ability or motivation to operate effectively within that context. Engaging in discussions with both foreign and local managers who have faced similar challenges can help alleviate these effects.

Lesson 2: Feel It! - Artificially Trigger the Update of Mental Models

As has already been highlighted, transforming experience into mental models does not happen without a trigger (Niittymies, 2020). For this, a strong disruptive stimulus is needed for the managers to “wake up” and create an initial sketch. Yet, the motivation for development is truly born when managers experience cognitive dissonance - highlighting that their existing ways of working are obsolete - and triggering the development processes.

Our point is that to achieve better understanding and decisions concerning integration into unfamiliar environments, managers should actively pursue challenging situations where they confront disruptive stimuli. A potential option would be sparring with managers from the target market, particularly those who have experience of both current and the foreign market. Through discussing their own views and ideas with these “opponents”, being repeatedly challenged, and reflecting on the differences, managers will obtain views that differ from their own understandings. This process is naturally very resource intensive and requires cultural sensitivity to avoid conflict at an interpersonal level. It is also possible that it would be culturally inappropriate to challenge others in certain cultures.

Fortunately, more economical possibilities have emerged to enable such opportunities. It has become possible to produce business-related decision-making scenarios using generative AI. These can be specified to aim at invoking cognitive dissonance based on a foreign country’s culture and habits. For instance, these scenarios can include previous mistakes leading to financial losses, customer complaints, and internal conflicts emerging from cultural differences, all of which facilitate the development of mental models through cognitive dissonance.

Lesson 3: Repeat it! – Change Should Be Continuous and Repeated

The former recommendations need to be done systematically to ensure the mental models develop and are best adapted to the foreign markets in which one seeks to better integrate. To ensure development is continuous, one should constantly accumulate experience and place oneself in challenging spots to maximize the stimulus needed for development. This can be accomplished through the interactions proposed in lesson 1. Moreover, updating or replacing incorrect mental models and cementing progress is not a one-shot learning task. Repetition is the key. Repetition is known to trigger a swift boost in knowledge formation. And not just repetition, but a particular variety called ‘spaced repetition’ where repetition happens with increasing intervals over time (Kang, 2016). This has been found to improve learning in difficult situations, such as medical school, particularly combined with active recall, i.e., needing to apply the adapted knowledge (Kang, 2016). In practice, managers should be repeatedly exposed to the target market, engage in vicarious experiences, and have their views challenged to keep their mental models current, and hence, be well placed to navigate the ever-changing IB environment. Table 1 presents a summary of the three lessons for integrating into a foreign market.

Conclusions

Successful integration is jeopardized when decisions are made using mental models calibrated for domestic or previous environments, which can lead to faulty decisions and detrimental consequences. In this paper, we present an integrative framework on how managers learn from disruptive stimuli, propose ways in which they can purposefully turbo-charge their learning in order to better integrate in foreign markets, and suggest how they can avoid potential pitfalls arising from continued use of obsolete mental models. We encourage managers to leverage the three lessons — Experience it!, Feel it!, and Repeat it! — to minimize the risks arising from mental model misalignment while maximizing their decision-making abilities in unfamiliar environments.

About the Authors

Aleksi Niittymies is an Assistant Professor of International Business in Aalto University School of Business. His research lies at the intersection of managerial decision-making and international business. He studies how managers’ decision-making processes unfold in the international environment, where the decisions are made under notable uncertainty as the managers struggle to make sense of the complexity of multiple different markets. His research has been published in Journal of World Business, International Business Review, and others.

Charlotte Walker (M.Sc) is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Management and Organization at Stockholm School of Economics, Sweden. Her research focuses on how organizations adapt to megatrends, specifically, how they develop dynamic capabilities, business models, and strategies for digitalization and sustainability.

Anna-Riikka Smolander is a doctoral researcher in International Business-unit and the Center for Knowledge and Innovation Research at Aalto University, Finland. She has several years of experience in cognitive brain research and applied AI which she is currently combining with management research. She has also held leadership positions in industry, serving as CEO of an AI-based EdTech startup and as Vice President responsible for internationalization at largest children’s coding school in Nordics.