Introduction

Trade conflicts and protectionist measures, global pandemics causing major supply chain disruptions, and the outbreak of an interstate war in Europe have raised awareness for geopolitics in boardrooms and corner offices around the globe. However, many companies have not yet fully integrated dealing with geopolitical events and developments into their business practices. A 2016 McKinsey survey found that the most popular method for addressing geopolitical risk are ad hoc analyses as events arise (Rice & Zegart, 2018). In Germany, even today, few companies systematically consider geopolitical risk factors in their risk management (PWC, 2023). According to a recent survey of board members in Switzerland, 69% claim that they “regularly discuss geopolitical developments” in board meetings, but only 12% receive geopolitical briefings and only 15% get a mapping of opportunities and risks (SwissVR, 2022).

The lack of management attention to geopolitics contrasts with another development: the increased focus on sustainability challenges and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in a company’s external business environment. Climate change, human rights, and tax transparency have become key concerns of various stakeholders, including investors, clients, regulators, and society at large. This is driven by a combination of regulatory, financial, operational, and societal considerations that reflect a broader shift towards more sustainable business practices.

The mounting sustainability expectations of various stakeholders have facilitated the emergence of practical approaches for dealing with ESG concerns. Such pressure, including reporting requirements, does not (yet) exist in the area of geopolitics. This article therefore proposes applying one of the central methodologies in the sustainability space – materiality assessments – to dealing with geopolitics. In doing so, companies can build upon tested practices and business experiences from the sustainability area to improve their handling of geopolitical challenges.

Responding to Geopolitical Risk

Geopolitical developments are influencing companies’ room for maneuver in international markets and in navigating the business landscape (Ciravegna, Hartwell, Jandhyala, Tingbani, & Newburry, 2023). These developments are mirrored in data showing an increase in geopolitical risk (Caldara & Iacoviello, 2022) as well as in executives’ risk perception (Giambona, Graham, & Harvey, 2017); this is reflected in regular surveys of business leaders conducted by McKinsey or the World Economic Forum.[1] Of course, companies have always faced a broad spectrum of geopolitical risks, ranging from political instability, war, and terrorism to riots and unrest or economic coercion such as expropriation or nationalization. Consequently, the study of this topic has a long tradition in international business and international relations (for an overview see Hartwell & Devinney, 2021; Jarvis & Griffiths, 2007). Various scholars have also investigated how companies specifically deal with the expectations, obligations, or constraints formulated by states or other political actors, focusing on individual companies (e.g., Mol, Rabbiosi, & Santangelo, 2023), industries (e.g., Jakobsen, 2010), or countries (e.g., Al Khattab, Awwad, Anchor, & Davies, 2011).

The academic literature offers less insight into how companies should respond to politically uncertain environments. Some authors with practical experience in both business and politics – and who are therefore perhaps more aware of the lack of coherent approaches in many organizations – have begun to develop systematic ways for dealing with geopolitics at the corporate level (e.g., Bremmer & Keat, 2009). Some urge companies to develop a form of “corporate foreign policy”, focusing on internal geopolitical due diligence and external corporate diplomacy in line with corporate interests (Chipman, 2016). Rice & Zegart (2018) suggest integrating geopolitical risk into processes and frameworks established for the management of other risk categories, while De Villa (2023) assesses the relevant issues in a multi-stage process after identifying a company’s exposure to geopolitical risks across multiple levels of analysis (supranational, international, national, industry, firm).

This article also proposes a step-by-step process for dealing with geopolitical risk. However, instead of directly building on risk management frameworks, it uses a core method of sustainability management: materiality assessments (Garst, Maas, & Suijs, 2022; Remmer & Gilbert, 2019). In line with widespread use in firms, the literature on materiality in sustainability has grown in recent years (Fiandrino, Tonelli, & Devalle, 2022). Although companies are generally reluctant to disclose detailed information about their approaches to identifying material topics and are evasive in disclosing their materiality criteria or decision-making processes (Fiandrino et al., 2022), the basic methodology is well established in the corporate world. From these foundations, it can be argued that the key strategic functions of materiality assessments – identifying material issues, prioritizing them according to risk and opportunities, and deriving strategic conclusions for corporate action – are also suitable for dealing with geopolitical risk.

Sustainability Standards and Double Materiality Requirements

ESG materiality assessments are an essential part of governance frameworks to manage sustainability risks and reporting requirements. They are enshrined in the most widely adopted global standards for sustainability reporting: (1) the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI); (2) the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which all companies in the EU are obliged to comply with from 2024; and (3) the IFRS Sustainability Standards, which provide a global baseline of sustainability disclosures focused on the needs of investors and other financial markets participants.[2]

The concept of materiality has its origins in financial reporting. It was first introduced in the U.S. Securities Act of 1933 and, since the 1940s, the US Securities and Exchange Commission uses the term “material information” in the context of financial statements for all matters that prudent investors need to know before purchasing securities (RATE/CCR, 2023). Starting in the 1990s, the exclusive focus on financial information was challenged by those pointing out that social and environmental information are equally important for a holistic understanding of a company’s situation. The GRI, founded in 1997, stipulated an alternative view on materiality, extending to the various aspects that are now bundled into the ESG agenda. However, the rationale behind “material” as such remains unchanged; companies must fully disclose any information – financial, social, environmental, etc. – that is relevant for stakeholders’ decision-making. If material information is omitted, misstated, or obscured, it would distort a company’s true situation and thus mislead stakeholders.

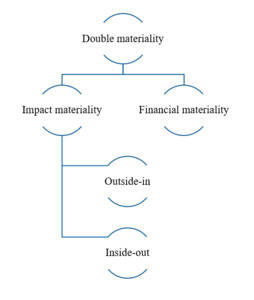

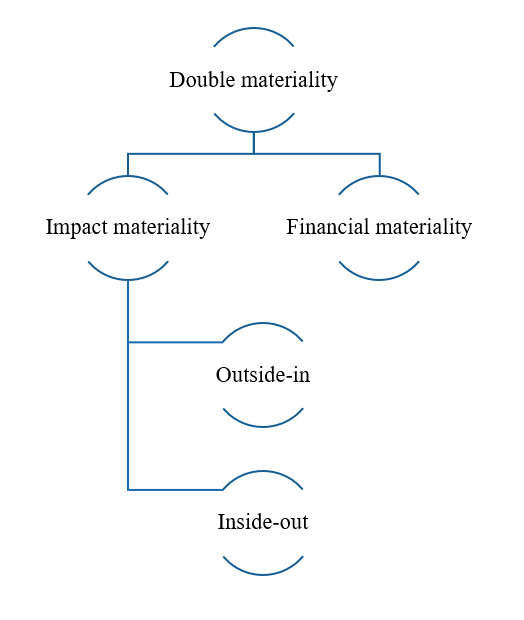

The IFRS Standards for financial reporting focus on financial materiality in line with the interests of an investor and financial markets participants audience, encompassing economic value and financial risks such as future cash flows, impairment of assets, tax implications, etc. In contrast, the GRI and the ESRS Standards target a broader stakeholder audience. They focus on a so-called double materiality approach, which, in addition to financial materiality, also considers a company’s impact on the economy, the environment, and society in general. Impact materiality has two components: (a) the impact of ESG issues on the company, i.e., all issues in the environment of a company that affect the strategic direction, the financial condition, the operations, or the reputation of a company (outside-in); and (b) the impact of the company on society and the environment, i.e., all issues that emanate from the company such as the carbon footprint or labor conditions (inside-out). Double materiality is the umbrella term for both impact and financial materiality. They are often interdependent because sustainability impacts regularly translate into financial effects for the company in the short, medium, or long terms.

Conducting a Materiality Assessment and Applying It to Geopolitics

The terminology used in materiality assessments differs between standard-setting organizations and from company to company.[3] Companies enjoy a significant degree of freedom to choose the approach that fits best their business model and industry, and they are advised to select the standards carefully (Garst et al., 2022; Remmer & Gilbert, 2019). While companies tend to be reluctant in disclosing information about their materiality definitions or processes (Fiandrino et al., 2022), in practice, they generally follow similar steps, according to a comparative analysis of ESG materiality assessments of 60 companies in Germany, Switzerland, the UK, and the U.S. (RATE/CCR, 2023).

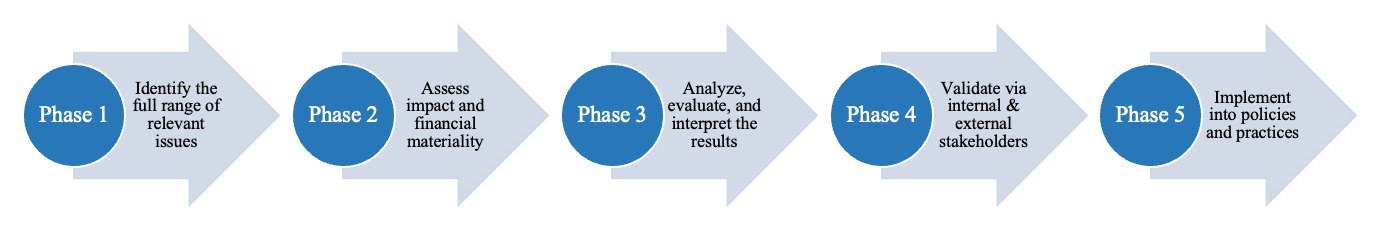

In phase one, the full spectrum of potential issues is mapped out and then reduced to a (short) list of issues that could affect the organization. This is usually done via desk research (across different environmental domains, specific industry-related information, etc.) and interviews with experts. In phase two, various stakeholders, representing an appropriate level of diversity (e.g., geographies, subject-matter expertise, professional backgrounds, age, gender), assess the short-listed issues and rank them in terms of impact and financial materiality. This is typically done through a broad range of quantitative and qualitative research methods such as surveys, data analyses, and interviews; often, methods are combined – a survey followed by expert interviews, for example – to achieve comprehensive results.

In phase three, the company evaluates the collected data, creates a priority matrix (combining impact and financial materiality), interprets the results, and prepares reports and other forms of communication. In phase four, additional stakeholders validate the outcomes to ensure that they accurately reflect the company’s context, threats, and opportunities. The executive management and the Board of Directors, but also important clients and investors may contribute. In addition, specialized auditors and experts are sometimes invited to comment and validate the process and results.

In the last phase, the findings are implemented into the company’s strategy, risk management, reporting, and other relevant processes. A materiality assessment reveals areas of action to which the company responds by setting new goals, developing policies, or starting initiatives in line with its business model, culture, or stakeholder expectations.

A geopolitical perspective can be seamlessly embedded in the five steps of materiality assessments: Identify the key geopolitical issues on the supranational, national, local, industry, and firm levels; assess their materiality considering, e.g., the company’s business model, market exposures, operational characteristics; derive and interpret the results; and validate the results with stakeholders. Ultimately, the conclusions are translated into corporate management responses such as scenario exercises focused on geopolitical changes, contingency plans for geopolitical crisis situations, permanent geopolitical monitoring capabilities, establishing internal bodies responsible for managing geopolitical exposures, procuring tailored information or intelligence on geopolitics, or the mitigation of identified threats from material geopolitical impacts in core business areas and support functions.

As the external environment continually evolves, materiality assessment is not a one-time activity (Garst et al., 2022). It needs to be revisited and updated regularly to reflect changes in the business environment, the sustainability landscape, altered stakeholder expectations, or new internal strategic or operational requirements. Given the rapidly evolving global landscape, this is also essential for managing a company’s geopolitical exposures.

Conclusions: Strengthen Geopolitical Capabilities

Materiality assessments enable companies to develop strategic capabilities (Remmer & Gilbert, 2019) that are equally useful for dealing with geopolitics as with sustainability concerns:

-

First, they act as a filter for risks and opportunities and thus help establishing effective risk management practices, including diversifying the supply chain, reducing reliance, defining the company’s risk appetite, and making the risk landscape transparent. In this respect, materiality assessments effectively complement the more established emphasis on integrating geopolitics into risk management processes.

-

Second, they provide a frame of reference that helps companies to decide on trade-offs, such as where to invest, where to expand operations, and which markets to enter or exit. This enables companies to seize opportunities that others might miss, and it may prevent firms from betting on markets that look promising but where the political environment could develop into substantial liabilities.

-

Third, they enable the inclusion of various stakeholders into the management of geopolitical challenges. This demonstrates a company’s willingness and ability to tackle difficult issues in a structured manner. Geopolitics then becomes more than a discussion item on the board agenda; it will be tangibly linked to corporate impacts. This makes the responsibility of the board and the C-suite visible, in terms of managing exposures and vulnerabilities. In this way, the company creates trust and strengthens its reputation among all stakeholders.

The fact that geopolitics is (once again) an important topic for corporate management has permeated the minds of business leaders and their companies in recent years, but many struggle in transferring these requirements into management systems. Materiality assessments offer additional ways of exploring a company’s exposure and vulnerability to geopolitical risks. Whether and how much importance a company attaches to sustainability management and the pursuit of ESG objectives, is not decisive. What counts is the fact that materiality assessments are already used by most companies (Garst, Maas, & Suijs, 2022) and can therefore easily be leveraged for integrating the geopolitical factor into management processes. Materiality assessments are therefore an additional element in the corporate toolbox, one that many organizations can tap into fast and without adding significant costs. This helps executives to achieve results quickly and to strengthen management capabilities in an area that seems set to become even more important in the future.

About the Author

Beat Habegger (beat.habegger@fhnw.ch) is a professor at the School of Business at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW), where he co-leads the Institute for Nonprofit and Public Management. Before joining the FHNW, he worked for over a decade in the private sector and was responsible for the sustainability and political risk management of a large Swiss multinational company. He holds a PhD from the University of St. Gallen.

In the March 2024 edition of McKinsey’s Economic Conditions Outlook, geopolitical instability and conflict continues to be the most cited risk to global growth: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/economic-conditions-outlook-2024. See also the World Economic Forum Global Risks Report 2024: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2024.

GRI Standards: https://globalreporting.org/standards; European Sustainability Reporting Standards: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-adopts-european-sustainability-reporting-standards-2023-07-31_en; IFRS Sustainability Standards: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/ifrs-sustainability-standards-navigator.

Cf., for example, the IFRS Practice Statement 2: Making Materiality Judgments (2023), which is applicable to a variety of contexts: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/materiality-practice-statement.