Attention from headquarters is important for foreign subsidiaries as it is usually accompanied by resources, financial investments, and project approvals. Managers in subsidiaries typically welcome headquarter attention as it can promote the status of their organization, expedite internal processes, and help obtain important mandates which in turn improve subsidiary performance. However, executives of multinational enterprises (MNEs) cannot pay attention to all subsidiaries which makes headquarter attention a scarce resource. This leads to the question: how do headquarters determine which subsidiaries require their attention?

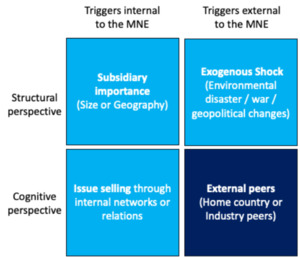

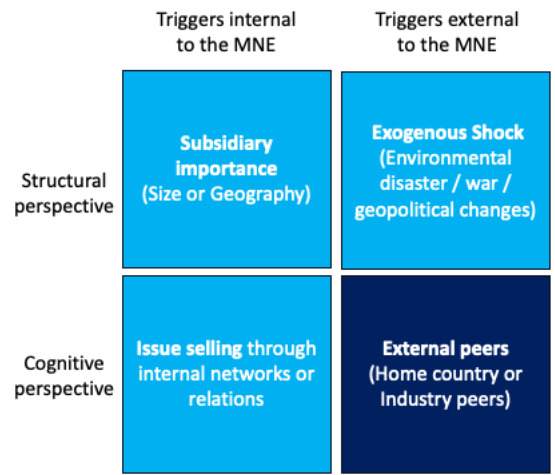

Traditional theories argue that headquarter executives pay attention to strategically important or flagship subsidiaries - those that contribute significantly to the MNE. The strategic importance is driven by the contribution the subsidiary makes to the overall MNE, in the form of sales, raw materials, manufacturing, or technology. This has been termed the “structural perspective” as it stems from the important role the subsidiary plays within the organizational structure of the MNE (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, 2008). Headquarter attention can also be triggered from outside the organization in response to exogenous shocks such as wars, major accidents or natural disasters, which are unforeseen and largely unpredictable events that can have profound negative effects on MNE operations. Here again, attention to a subsidiary is based on its structural role within the MNE (Lee & Chung, 2022). Figure 1 illustrates these two triggers.

Another mechanism through which headquarters distributes attention is in reaction to subsidiary-level attempts at issue-selling, such as self-promotion or internal lobbying efforts. These actions are triggered from within the firm by its subsidiaries (Figure 1), but the emphasis is on how to present issues to effectively appeal to headquarter executives. Therefore, this is referred to as the “cognitive perspective”. For instance, Bouquet and Birkinshaw (2008: 583) quote one manager talking about ‘preselling’ a project internally to various teams before presenting it to headquarters so that there is critical support in place for his project. The stimulus here comes from inside the MNE, initiated and promogulated by the firm’s subsidiaries. Within the cognitive perspective, headquarter attention can also occur independent of subsidiary actions or initiatives, triggered by something external to the MNE as seen in the lower right quadrant in Figure 1. However, this quadrant is less understood especially given the diversity and complexity of an MNE’s operations. This prompts the fundamental question, which external cues do headquarters pay attention to? We focus on external peers as one such external cue. External peers, defined as other firms in the competitive environment, are a stimulus because it is well established that firms pay attention to other firms. However, the relevance of this issue in the context of headquarter attention raises the following questions:

-

WHO are the external peers that managers monitor? The cognitive perspective is particularly relevant here because managers have cognitive limits which necessitates the creation of a small enough set of firms to be monitored. Cognitive frameworks are filters through which managers process external stimulus, which consequently define who is a relevant external peer.

-

WHAT subsidiaries benefit from external peer attention to their own subsidiaries? Some subsidiaries may garner headquarter attention on their own because of their own actions or owing to their considerable size. These are considered ‘strategically important’ subsidiaries. The cognitive perspective enables us to understand headquarter attention that goes beyond these factors, specifically how strategically unimportant subsidiaries may gain headquarter attention. This can benefit both headquarters and these subsidiaries by shifting focus in a manner that reduces potential biases caused by structural considerations.

-

WHEN are external peers more likely to be relied upon by managers? Significant events may undermine or reinforce the usefulness of prior cognitive frameworks. The cognitive perspective informs us that changing dynamics introduce uncertainty about what specific factors will come into play.

These questions are particularly relevant for students and managers to better understand the cognitive factors that drive headquarter attention. The basic idea is that attention by external peers to their subsidiary(ies) in a foreign market prompts MNE managers to pay attention to their own subsidiary(ies) in the same market. Our insights are informed by interviews with MNE managers and consultants as well as empirical research on headquarter attention to subsidiaries (Sewak & Lamin, 2023).

WHO are the external peers that managers monitor?

In a seminal paper on the Scottish knitwear industry, scholars discovered that who they considered to be competitors were not the same firms that executives defined as competitors (Porac, Thomas, & Baden-Fuller, 1989). Executives viewed firms with whom they overlapped geographically as competitors, meaning they were headquartered in the same home market. Firms headquartered overseas were not viewed as relevant even though those firms exported and sold clothes in the same market. This study was part of a wave of research on executive cognition that occurred in the 1990s. The results of this research produced a few simple ideas:

-

Executives cannot attend to everything all at once, so they rely on cognitive frameworks to process and categorize information. Cognitive frameworks filter external cues into different cognitive categories.

-

The cognitive categories developed are usually based on simple perceived similarities or differences: e.g., domestic vs. foreign, national vs. regional, downtown vs. suburban.

-

These categories determine who is considered a competitor; in other words, firms that fall within a category are said to be part of a peer group. These peer groups are important because they are deemed more relevant than other firms, and thus, become the focus of attention.

-

Firms’ strategic response is shaped by their attention to these peer groups.

The reason this research was so influential is that it ran counter to the ‘rational actor’ model propagated in economics, which suggests that an appropriate peer group is all market rivals with whom the firm competes for market share and profits. However, managers do not do systematic market research but instead rely on feedback from a narrow group of actors they view as relevant. Essentially, managers pay attention to a small set of peers to devise their strategies.

Building on the idea that executives use categorization to develop key peer groups, we suggest that competing in the same foreign markets is a condition especially relevant for MNEs. This comes directly from the cognitive perspective, which emphasizes geographic overlap as a critical component for the cognitive definition of competition (Baum & Lant, 2003; Porac et al., 1989). By competing in the same foreign market, MNEs become not just global competitors but also local rivals. However, an MNE cannot attend to all foreign subsidiaries across all markets as this would simply be too cumbersome. Thus, an additional dimension of similarity is required. We focus on two additional common dimensions – same-industry and same home-country overlap – and examine whether these dimensions are relevant cognitive categories of external peers.

-

Same home-country: In international business, firms from the same home country follow each other abroad and use similar entry modes suggesting that this is an appropriate reference group (Henisz & Delios, 2001; Lu, 2002). An example of same home-country firms are 3M and General Motors, who are both headquartered in the U.S., although they are in different industries. The ease with which home country firms are observable likely plays a key role. However, less is known about the extent to which home-country overlap influences decisions post-foreign market entry.

-

Same-industry overlap: Industry overlap is commonly viewed as a relevant category, but this is usually examined within a firm’s home country or again as it applies to foreign market entry (Li, Yang, & Yue, 2007). An example of same-industry overlap is Ford and Toyota, which are both in the automotive industry. However, these firms may not be headquartered in the same country. The extent to which this applies to activities within host countries is less clear.

We suggest that as external peers – either same-home country peers or same-industry peers – increase their attention to their subsidiaries in a host market, the salience of the market increases; this causes the MNE to focus attention on its subsidiary in the same host market. We found that having a subsidiary in the same foreign market and same industry is a relevant reference group (Sewak & Lamin, 2023).[1] When headquarters see same-industry firms pay attention to their subsidiaries in a foreign market, this then triggers managers at headquarters to pay attention to their subsidiary in the same foreign market. However, headquarters are less likely to pay attention to peers from the same home-country. In short, headquarter attention to subsidiaries is influenced by the attention same industry-peers bestow to their subsidiaries in the same foreign market but not by home-country peer’s attention to their subsidiaries. In terms of WHO is considered an external peer, it is firms from the same industry that have subsidiaries in the same foreign market.

Managerial insights. Table 1 explores the implications for both headquarter and subsidiary managers of this insight as well as provides evidence from our interviews with MNE executives. For headquarter managers, organizational structure (the “structural perspective”) and intra-firm relationships can create internal biases that hinder effective decision-making at headquarters concerning the importance of foreign subsidiaries. This is especially the case when subsidiaries engage in issue-selling or large subsidiaries demand resources. However, headquarter managers can minimize the impact of internal biases by integrating same-industry peer information in decision-making processes. By following same-industry peers, headquarter managers can focus attention on subsidiaries that may otherwise be overlooked, identifying new opportunities or critical issues. From the perspective of subsidiary managers, industry peers’ attention and strategic initiatives can be used to enhance their arguments for greater resources, investments or autonomy from headquarters. Same-industry peers within a foreign market can thus provide a relevant basis for subsidiary requests to headquarters.

WHAT subsidiaries receive attention in this manner?

Next, we explore what types of subsidiaries receive attention. We divide subsidiaries into two types: (1) strategically important and (2) strategically unimportant. From the structural perspective, we know that strategically important subsidiaries – those that account for a significant portion of an MNE’s sales – are clearly on the radar of headquarter executives. Stemming from their importance to the overall firm, these subsidiaries receive headquarter attention regardless of what external peers are doing. What about strategically unimportant subsidiaries, those accounting for just a small fraction of an MNE’s sales? Traditional theories suggest that these subsidiaries struggle to gain headquarter attention as they occupy less central positions in managers’ minds. The typical advice is to turn to internal lobbying to build up their profile or undertake initiatives that capture headquarters’ attention. However, there is another way by which these strategically unimportant subsidiaries may garner headquarters’ attention. Specifically, headquarters can witness external industry peers’ focus on their own subsidiaries, enabling the strategically unimportant subsidiaries to secure a larger share of headquarters’ cognitive capacity. In fact, attention by same-industry peers to their own subsidiaries prompts headquarters to pay attention to its own subsidiaries in these markets even when they are strategically unimportant. But, attention by home-country peers to their subsidiaries does not spur headquarters to pay attention. Similarly, attention by other firms (those with subsidiaries in the same market but in other industries or from other home countries) to their subsidiaries does not affect headquarters attention in strategically unimportant markets. In this manner, same-industry peers play a meaningful role in improving visibility and securing headquarter attention for subsidiaries in markets that are less strategically significant. It is precisely under these conditions that cognitive frameworks come into play, where increasing attention to a subsidiary market by external peers triggers increasing attention by the focal firm to the same market.

Managerial insights. Table 1 summarizes the managerial implications. For headquarter managers, even subsidiaries with low relative sales or profitability may hold significant long-term potential. Competitor actions and investments can help define the importance of markets or identify new market opportunities in a subsidiary’s market. For subsidiary managers, industry peer actions can create short-term negotiating power to an otherwise power-deficient subsidiary. Peer actions enable managers within a subsidiary to sharpen their message and seek resources that would otherwise be unavailable to it.

WHEN are external peers more likely to be relied upon by managers?

How do changes in the environment affect the influence of external peers on headquarter attention to subsidiaries? Large changes in the general environment can undermine the usefulness of prior cognitive frameworks, rendering portions of these frameworks ineffective. It is difficult for firms to know how to respond as big environmental changes introduce elements of uncertainty. Volatility creates challenges for prior categorizations as they may be deemed less relevant or headquarters may become overwhelmed by environmental cues. Environmental changes can encompass macroeconomic factors such as changes along social, economic, and political dimensions. However, it should be noted that cognitive frameworks are highly resistant to change even when they are rendered ineffective in helping managers make sense of new environmental conditions (Bogner & Barr, 2000).

We looked at two types of environmental changes – economic and political – to determine whether these diminish the relevance of external peers to headquarters’ attention towards its subsidiaries. Economic shocks may restrict or redirect the opportunities available within a market which may in turn prompt executives to expand their cognitive frameworks and strategic attention to find suitable opportunities (Eklund & Mannor, 2021). Meanwhile, changes in political power can represent serious political hazards that may impact an MNE’s assets and activities in a foreign market. In assessing how to respond to political hazards, executives often draw on their established cognitive categories in developing appropriate responses (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015). In our analysis, the economic change was the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 while the political changes were the national elections in India in 2004 and 2014 in which the incumbent party lost.

We found that cognitive frameworks are persistent and resistant to change. The effect of external peers on headquarter attention to subsidiaries did not diminish during either the global financial crisis or the political changes. Same-industry peers remained important during these times of environmental turbulence and same home-country peers continued to be insignificant. The findings suggest that MNEs operating during environmental changes do not adjust their frameworks in terms of headquarter attention to subsidiaries. General environmental turbulence impacts all firms and does not change the relationship between significant actors. In response to these types of environmental hazards, the basic relationships remain predictable and largely stable; thus, MNE executives continue to rely on external peers to help direct their attention to subsidiaries through these types of uncertainty.

Managerial insights. When facing increased environmental turbulence, headquarter executives rely on what peers are doing to help navigate it, as summarized in Table 1. Attention to peers can help managers develop a blueprint for traversing situations with increasing country hazards and risks. Peer actions can serve as ‘recipes for success’ during times of uncertainty. In fact, during these times, peers can help identify the appropriate timing of action. From the perspective of subsidiary managers, peers’ ‘recipes for success’ can be used as baselines from which to build their own strategic responses. Understanding peer responses to current market conditions can help subsidiary managers inform their own decisions. Using peers’ actions as a baseline can help companies navigate downturns and uncertainty to gain an advantage over competitors.

Conclusion

We highlight the prominent role of cognition in shaping headquarter attention to subsidiaries. MNE’s global actions can be defined by responses to not only internal triggers but also external ones. Although we know that subsidiaries can gain headquarter attention through their actions and contributions to the MNE, we argue that same-industry external peers influence headquarter managers in the way they direct attention to their subsidiaries. This is especially relevant for strategically unimportant foreign operations which would otherwise rely on issue selling and other initiatives to gain headquarters’ interest. Headquarter attention, like all attention, is inherently a cognitive process and governed by a repertoire of cognitive frameworks. Headquarter managers balance their global operations through these frameworks which allow them to simplify this complexity. These insights advance our understanding of how headquarters allocates attention and resources, offering useful insights on managing the complexities of a global corporation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their support, comments, and guidance in developing this paper. In addition, Professor Valentina Marano provided invaluable feedback and input in the development of the paper. We would also like to thank the managers who helped us during our research.

About the Authors

Mayank Sewak, PhD, FHEA, is a Lecturer in International Business at the Newcastle University Business School, Newcastle University, UK. In his research he focusses on strategies and management of multinational enterprises with specific interests in headquarter-subsidiary relationships and local knowledge for subsidiaries in emerging markets. His research has appeared in Journal of International Management, International Business Review and Management International Review.

Anna Lamin, PhD, is an Associate Professor of International Business and Strategy at Northeastern University. Her research centers on how firms in emerging markets build capabilities. She examines how innovation clusters influence firm location decisions, how business group affiliation affects strategy, and headquarter attention to subsidiaries. She currently serves as a Senior Editor for Asia-Pacific Journal of Management and serves on the Editorial Review Boards of Journal of International Business Studies, Global Strategy Journal and Journal of World Business.

To measure headquarter attention to subsidiaries, we followed established practice and used word counts in annual reports (Nadkarni & Barr, 2008). While this measure may seem coarse, it has been shown that shareholder documents accurately reflect topics managers pay attention to internally (Fiol, 1995).