Introduction

Stigma is the mark of a condition or status that is subject to devaluation (Goffman, 1963), and stigmatization is the social process by which the mark affects the lives it touches. Stigmatization can occur due to attributes such as race, weight, gender, nationality, minority group membership or external events (Moeller & Maley, 2018). Stigma is socially constructed and based on relationships between the above-mentioned attributes and stereotypes. Hence, stigma is perceived in varying ways based on continuously evolving social, political and economic aspects of home and host markets, including critical events such as war. In international business (IB), displaced employees, migrants and expatriates may be stigmatized due to various inclusion gaps in both home and host countries (Falcão, Silva-Rêgo, & Cruz, 2024; Newburry, Rašković, Colakoglu, Gonzalez-Perez, & Minbaeva, 2022). These displaced people face a number of social, political and economic challenges arising from stigma. Because these challenges differ from country to country, multinational companies (MNCs), displaced employees and expatriates must adapt and respond to each unique set of circumstances from which these challenges spring (Sindila & Zhan, 2024).

We use the case of Russian academics abroad to examine how displaced employees deal with the stigma of Russian nationality that has emerged as a result of the war against Ukraine. These academics are not expatriates as such; some of them are displaced academics who had to relocate to foreign universities shortly after the war began and who had to go through an acculturation process as expatriates do. Others are Russian academics abroad who relocated to foreign universities several years ago or before the war started. We acknowledge the sensitivity of this topic, and that Ukrainian people have been suffering significantly as the consequences of the war. We draw on the current literature on stigma, adopting research approaches and empirical data to identifying four types of coping strategies: confronting stigma, collective consolidation of stigma, circumventing stigma and self-isolation. We provide practical recommendations on how displaced citizens can deal with being stigmatized and how MNCs can help these citizens deal with being stigmatized. The objective of the paper is to shed light on stigmatization in IB literature and stimulate future scholarly discussion and research on this topic.

Stigma and Coping Strategies in the Literature

There are four types of stigma: self, public, professional, and institutional (Pescosolido & Martin, 2015), and the stigmatization process requires the presence of four conditions. First, it depends on the power and the ability to differentiate and label the differences. Second, only social relations can enact stigmatization. Third, shaping stigma occurs in a particular social context (i.e., time and place). Fourth, all components of stigma exist as a continuum (Pescosolido & Martin, 2015). Expatriates can go through the stigmatization process, and their experience with stigma may vary, depending on what initiated this process. The way organizations treat expatriates and migrants while they are going through the stigmatization process may significantly impact their acculturation process. Thus, organizations can play a key role in educating all employees about the stigmatization process and how it can impact expatriates’ experiences and perceptions of their time overseas.

Stigma theory posits that membership in a negatively stereotyped group leads to low self-esteem and self-hatred (Brown, 1998). For example, Mobasher (2006) described Iranian immigrants in the United States, following the Iranian revolution and hostage crisis of 1979, as feeling self-hatred, shame, inferiority, insecurity, and deep American antipathy toward Iran and Iranians. When people are linked to undesirable characteristics, it gives reason for devaluing, rejecting and excluding them (Moeller & Maley, 2018). This is relevant for MNCs because expatriates face inclusion gaps in home and host countries (Falcão et al., 2024; Newburry et al., 2022) based on the characteristics listed above. MNCs can play a significant role in teaching expatriates, migrants and local employees how to deal with stereotypes – both those who are victimized by them and those who engage in stereotyping.

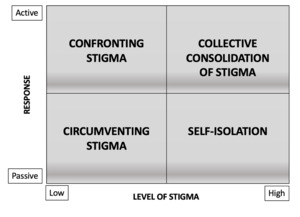

Many individuals emphasize the positive in stigmatized identities, especially in terms of occupations: Dog catchers console themselves by believing that they are helping to prevent the spread of rabies, and gravediggers emphasize the joy of being outdoors (Palmer, 1978). Brown (2015) delineated three coping strategies for handling stigmatized identities: (1) establishing a protective ideology; (2) using behavioural and cognitive defence tactics, such as humour and ambivalence; and (3) stigmatized workers reframing, recalibrating, and refocusing their understanding of themselves, thus securing a positive self-understanding. Furthermore, international migration literature emphasizes the fact that host countries’ migration policies serve as barriers against migrants’ opportunities to acculturate in those host countries (Kothari, Elo, & Wiese, 2022). These barriers make coping with stigma more challenging. We developed a typology of stigmatization strategies, which spans a continuum based on level of stigma and density of social relations, illustrated in Figure 1.

The Case of War’s Effect on Academics Abroad

We use Russian academics abroad as a case study. Many Russian academics abroad are experiencing severe psychological, cultural, personal, and professional damages and losses after the beginning of the war on 24 February 2022. Although these harms are not comparable to what Ukrainian citizens are suffering, their study is nonetheless important. Russia’s scholars and scientists constitute one of the most independent-minded and globally integrated groups, facing choices they have never before confronted (Deriglazova, 2022). We studied two groups of academics: those who left Russia several years ago, and those who had to leave Russia after the conflict began. We employed a mixed-methodology study. On the basis of data from 265 surveys and 30 in-depth interviews, we provide insights into how Russian academics abroad responded to stigma after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The dominant age group of surveyed participants was 30–39 years old, accounting for 36.7% of the respondents. Female academics accounted for 44.5%. Ph.D. respondents accounted for 18.2%, one of the largest representative groups, with other groups more or less equally represented. The most common field of study was Management, Business, and Economics (39.9%); followed by Humanities, Culture, Art, and Languages (17.5%); then Mathematics, Physics, Astronomy, and Earth (12.1%). We acknowledge over-representation of business school scholars in the sample due to their specific IB knowledge and ability to converse in English language. The sample represents more than 40 host countries, with the largest representations from the U.S., Germany, Australia, Finland, the UK, France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Ireland. This representation illustrates that human resources dislocations and migration is an important IB issue because organizations employ many expatriates and migrants. Organizations must take a leading role developing policies and practices for displaced citizens and people who have been affected by crisis events (Falcão et al., 2024; Newburry et al., 2022).

A Typology of Responses to Stigma

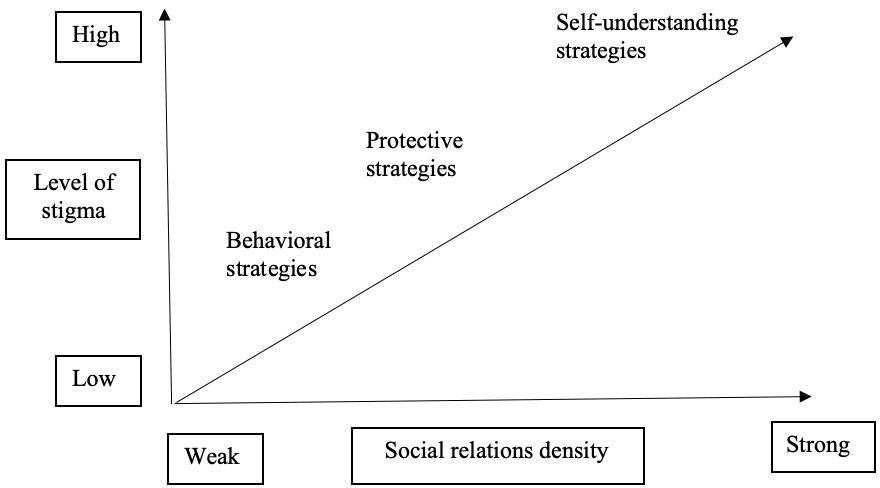

Figure 2 illustrates a typology of responses to the stigma, based on active or passive response and whether the perceived level of stigma was high or low (Brown, 2015; Pescosolido & Martin, 2015).

Confronting Stigma

This group of academics reported experiencing a low level of stigma due to their personal characteristics or stronger focus on action rather than on reflection. Hence, they respond to stigma by confronting it with action. By confronting the association of critical events in home markets, these academics showed emerging leadership by devoting themselves to their academic activities and outcomes. They reported not having time to experience stigma or reflect on being Russian during the war – nor for self-pity or passivity – and prioritized action.

These academics undertook diverse activities to respond to stigma: ‘Instead of being aside and thinking “I’m Russian, I cannot do much in this situation,” I said “I’m Russian and because of that I’m going to do so much”’ (Academic, Iceland). ‘Like everyone, [we] felt the urge that we have to do something. We have to support colleagues who are refugees from Ukraine or Russia. We have to kind of do something about the whole situation’ (Academic, Finland). Some were fully committed and devoted to confronting stigma: ‘More aggression, more projects, more activity’ (Academic, Iceland). This is in line with the behavioural strategies that we developed in Figure 2. Confronting stigma through these strategies can help displaced personnel, migrants and expatriates to deal with it while abroad on international assignments.

Collective Consolidation of Stigma

This group of academics view stigma as high and actively respond to it. Collective consolidation is important in times of traumatic events, but it has not been studied as much as individual consolidation (Eijberts & Roggeband, 2016). Participants reported that collective consolidation, such as through re-engaging or deepening their ties with other Russian academics abroad, helped them to create the collective community and action, by actively engaging in sharing knowledge and relying on their colleagues. A participant from Finland stated, ‘I found a relief in sharing the pain with other Russian abroad, with other Ukrainians abroad, with other country nationals who were affected by war by sharing the circumstance and actively helping to each other’. The power of the invasion’s shock and stigma were immense: ‘I wouldn’t know how to manage the situation when the war started. I spoke about it with my students, and I started crying in the classroom’ (Academic, UK).

Strong social density is crucial for migrants and expatriates (Pescosolido & Martin, 2015). The collective consolidation of stigma provides a platform for displaced academics, migrants and expatriates to cope with negative reactions and attitudes targeting them. It is important for these groups of people to share their knowledge, experience, and opinions with various stakeholders because it can help them to reduce the exclusion gap that they may face while abroad on an international assignment (Falcão et al., 2024; Newburry et al., 2022).

Circumventing Stigma

This was the predominant strategy, as most respondents viewed their level of stigma as relatively low and engaged in very passive responses. Although critical events such as war can traumatize migrants and expatriates, many participants continued life as usual, circumventing Russian cultural identity by replacing it, often with focusing on professional identity. More senior academics demonstrated more strength and stability: ‘This is my job. I should do it at the higher level. It does not matter where I am. I had to develop some new courses and teach them well’ (Academic, France). The majority of the participants agreed that while experiencing stigma, they tried to replace their Russian cultural and personal identities with their personal and community identities. Others reported finding refuge and significant strength in replacing their cultural identities with their professional ones: by ‘being not Russian, but a business researcher’ (Academic, Finland). ‘I tried to emphasize my professional identity at work, where I don’t bring my cultural identity’ (Academic, Ireland). Similarly, another academic said, ‘I focus on my international research identity more than on my Russian background’ (Academic, Australia). Because displaced labour tries to lose the membership of the stigmatized home market (Brown, 1998), MNCs must understand that losing national membership for migrants or expatriates can have significant implications on their ability to perform.

Self-isolation

This group of participants reported significantly impactful experiences of stigma but engaged in very passive responses, where higher number of respondents demonstrated introversion characteristics. A significant number of the interviewees reported high levels of cultural loss immediately after the war started. One participant stated, ‘I was in shock. The night-time was the most helpful time for me. I just wanted to go to bed and sleep and not wake up’ (Academic, Australia). Many reported a high level of stigma, apathy and passivity: ‘Research and teaching, everything felt very meaningless. Like, why? Why do I even do it? Does it even matter when people are dying?’ (Academic, Spain). Another reported loss of relevance: ‘You feel like, why are you teaching these topics if there’s much more crazy stuff happening in the world? Like, it doesn’t matter. It feels like everything should be about the war and not about what you’re doing’ (Academic, the Netherlands). Several respondents felt that their national cultural background mandated that they step down from positions of leadership, or not take up visible public positions: ‘I felt like I have less of “right” to take up the leadership position’ (Academic, Finland). ‘It takes some effort to take the same position and persuade myself that I have rights to do my work’ (Academic, Australia).

Other academics reported their withdrawal from the positions of power and associations with the regime: ‘I was a member of different academic committees in Moscow and St. Petersburg. I had to cancel my membership in all of these committees. I had to withdraw my name from all the committees in Russian universities’ (Academic, Finland). Another participant stated, ‘Yes, I quit. I quit the Russian university. It was my decision because I realized that I cannot do it anymore in this situation and share those values’ (Academic, Belgium). Several reported: ‘I don’t want to be Russian anymore’ (Academic, UK), ‘I’m used to be[ing] proud of my Russian background’ (Academic, Australia), and ‘This event was undoubtedly . . . catastrophic for my Russian identity’ (Academic, Finland). In most cases in a given category, self-imposed stigma impacted individuals’ perception of public stigma. Migrants, expatriates and academics face social and political challenges (Sindila & Zhan, 2024), but because of the national stigma due to critical events, instead of employing self-understanding strategies (presented in Figure 1), these groups tent to enter self-isolation stage of coping process (presented in Figure 2) due to their perception of public stigma.

Coping Strategies and Recommendations

The study serves as an important contribution to knowledge on responses to stigma during critical events.

Implement Formal Coping Strategies

Organizations are responsible for providing support because displaced citizens experience more impact of stigma. Given the lack of formal support illustrated by this paper’s findings, organizations can support these individuals by implementing formal and informal support systems. The responses in the typology – confronting, collective consolidation, circumventing, and self-isolation – could be used as a guiding point to identify individuals who experience the impact of national stigma. This research can also help to institutionalize these strategies through organizations’ policies to formalize necessary support systems.

Develop Informal Coping Strategies

Social relations and collectively dealing with stigma proved to be significant in our study. Hence, organizations must develop online and physical platforms for migrants and expatriates to be able to connect with other colleagues who have experienced stigma, in both home and host markets.

Educate Employees

Organizations should educate all employees – regardless of whether they are affected by stigma of their home country – about the four possible coping strategies these stigmatized employees might experience. This will significantly impact the acculturation process of expatriates and migrants and help them navigate the challenges that they may confront due to stigmatization. Organizations should also educate employees who are not affected by stigma about the impact that stigma may have on employees who are experiencing it as well as coping strategies these employees might apply. Such education can help these employees to organically develop informal coping strategies. Developing supporting culture organizational culture can help managers to increase the wellbeing of their employees, which can in turn help to improve or maintain the organization’s reputation for being proactive and supportive of citizens who experience national stigma.

About the Authors

Marina Iskhakova is a Senior Lecturer at Australian National University. Her research interests include cultural intelligence, international experience, cross-cultural management, international education, short-term study abroad and the most recent – sanctions in IB. Her work on international experience and cultural intelligence not only fostered a deeper understanding during development of the College of Business and Economics’ Global Business Immersion programs, it contributed to program design. Marina’s research has appeared in Critical Perspectives on International Business, International Journal of Manpower, Studies in Higher Education and Journal of International Education in Business.

Anna Earl is a Senior Lecturer in Management at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Her main research interests include: impact of sanctions on IB, and internationalization processes of MNCs from emerging economies. Anna has published in Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Journal of International Management, Critical Perspectives on International Business, International Journal of Emerging Markets and Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal. Anna is on editorial boards of Journal of International Management, Review of International Business and Strategy and International Journal of Emerging Markets.