Introduction

The 2023 UN SDG report highlights a significant shortfall from expected progress, particularly in low and lower-middle-income economies (Dau, Moore, & Newburry, 2023; Sachs, Lafortune, Fuller, & Drumm, 2023). These nations are disproportionately affected due to their lower initial conditions and a decline in international support, driven by adverse external shocks. Among these shocks are the economic challenges of the post-COVID-19 era, which disrupted global supply chains and hindered recovery efforts; the ongoing US-China trade rivalry, creating uncertainties in trade flows and investments; the war in Ukraine, intensifying geopolitical tensions and disrupting global food and energy supplies; and inflation, which erodes purchasing power and destabilizes financial systems. These cumulative shocks strain resources and derail progress on key SDGs by exacerbating inequalities (SDG 10), and poverty (SDG 1), slowing economic growth (SDG 8) and possibly innovation (SDG 9). This is particularly acute in low- and middle-income economies. In this paper, I explore how emerging market multinational enterprises (EMNEs), with their regional knowledge and innovative capabilities, can act as critical drivers to propel these nations toward achieving their UN development goals.

International business scholars have identified distinct traits of EMNEs with respect to multinational enterprises from developed economies (MNE) in their internationalization and competitive strategies (Hernandez & Guillén, 2018; Ramamurti, 2009). I argue that some of these unique qualities make EMNEs vital players in supporting developing economies to meet the UN SDGs. First, EMNEs are naturally attracted to developing economies due to their ability to leverage the abundant semi-skilled and unskilled workforce available in these regions. This approach aligns with their cost leadership strategies, which focus on maintaining operational efficiency while delivering competitive pricing. By doing so, EMNEs not only create employment opportunities in low-income regions but also reduce poverty (SDG 1). Moreover, the economic inclusivity fostered by employing a diverse local workforce helps reduce inequalities (SDG 10), particularly in regions where traditional MNEs are less inclined to invest due to higher operational uncertainties and lower consumer purchasing power. Second, EMNEs excel in scaling their regional and global presence by building on their knowledge and experience in other developing markets. Their ability to operate efficiently in challenging environments allows them to expand both in factor and product markets rather smoothly. This makes collaboration with Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) very promising given the type of products and nature of customers they serve in the region. This collaboration is mutually beneficial, as SMEs gain access to global value chains, and EMNEs benefit from local insights and supply chain integration and strengthen their presence in these regions at a faster pace. These partnerships are vital for fostering decent work and economic growth (SDG 8) and reducing inequalities (SDG 10) by creating more inclusive economic opportunities and enabling SMEs to thrive in competitive markets. Third, EMNEs demonstrate an exceptional ability to understand local market challenges and consumer needs, which allows them to develop innovative, tailored products. These products often address specific infrastructure deficiencies, such as unreliable electricity or poor transportation networks, and improve access to essential services. By focusing on localized features and affordability, these innovations empower less affluent consumers while fostering entrepreneurship and economic empowerment. These contributions are central to advancing industry, innovation, and infrastructure (SDG 9) and promoting inclusive economic growth (SDG 8).

The distinctive characteristics of EMNEs—ranging from their ability to navigate institutional uncertainties to their expertise in frugal innovation and local market adaptation—make them indispensable in addressing the unique challenges faced by developing economies. These strategies enable EMNEs to reduce poverty (SDG 1), foster economic growth and innovation (SDG 8 and SDG 9), and reduce inequalities (SDG 10), directly contributing to the global SDG agenda. The following sections will go deeper into these roles, exploring the ways in which EMNEs can drive sustainable development and providing actionable recommendations for key stakeholders.

How Do EMNEs Advance SDGs in Developing Economies?

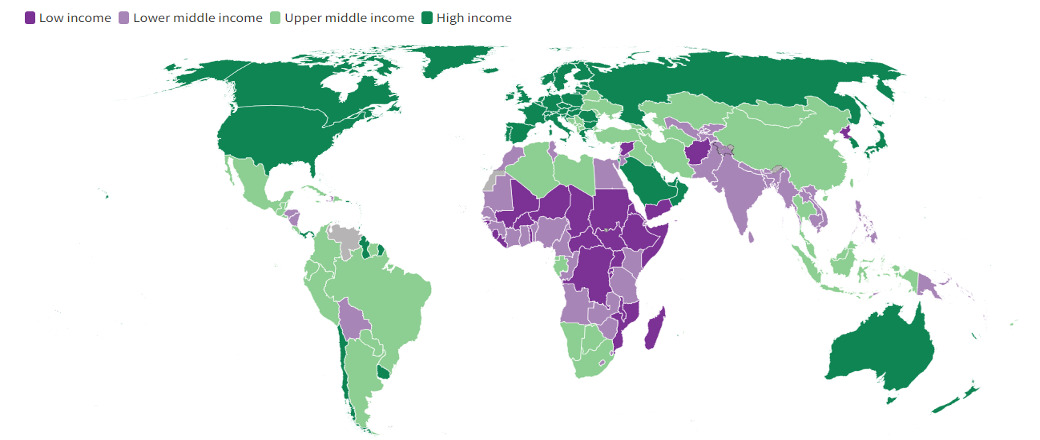

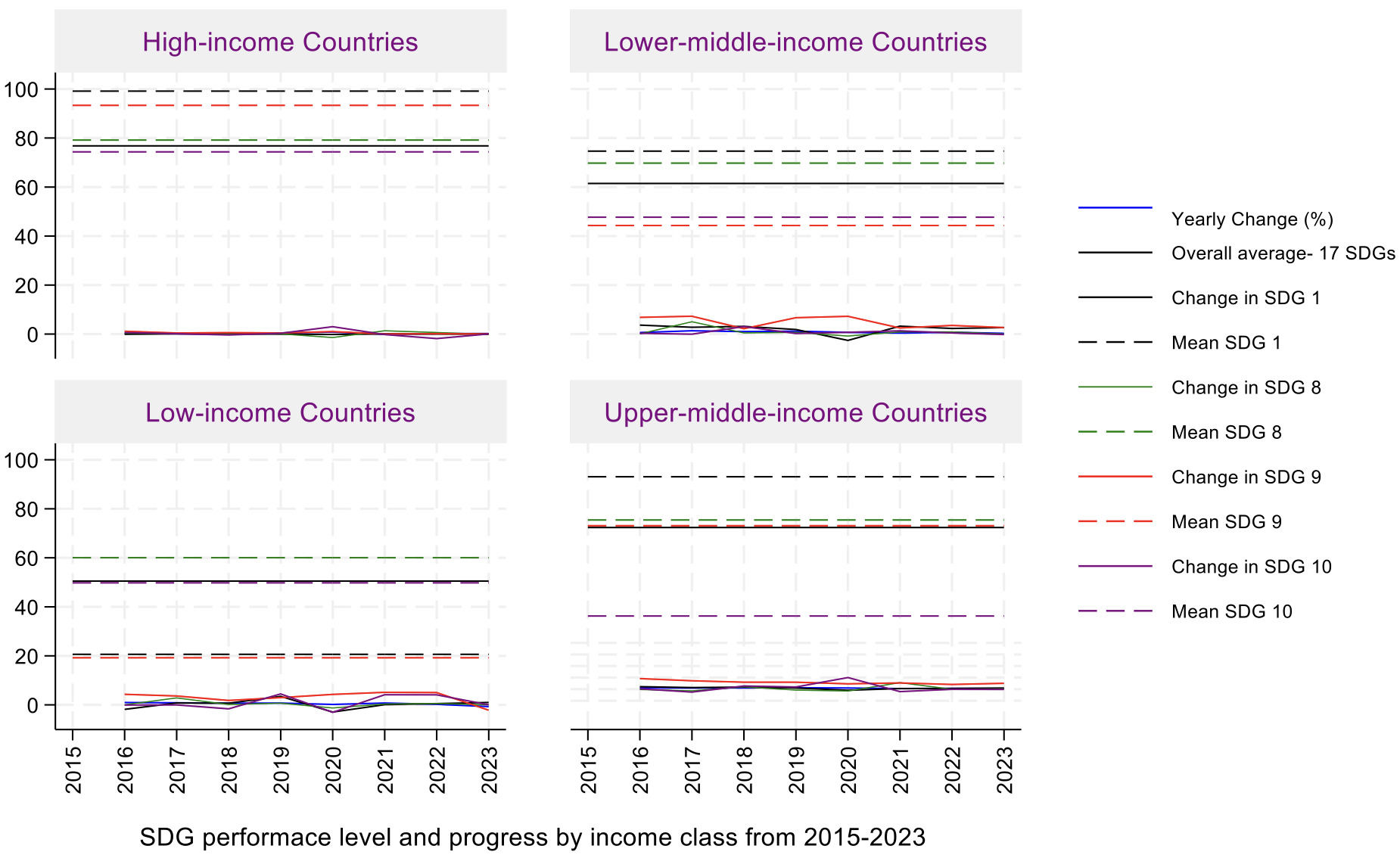

Based on the World Bank’s economic classification (see Figure 1), more than 80 economies are classified as low- and middle-income, which will hereafter be referred to as developing economies. These economies are dispersed across all the continents with a major concentration in Sub-Saharan Africa. Figure 2 presents the status of these economies in comparison with developed economies on their SDG performance. This figure highlights two key points: First, it shows that low- and middle-income economies generally have lower average performances on SDGs compared to upper-middle and high-income economies. Although this is expected, as the SDG goals anticipated significant improvements from these economies due to their lower starting points, the actual data reveal a concerning trend. The year-to-year changes in their SDG performance are minimal, and in some cases, even lower than those economies that are already a good starting point. The underperformance of low- and middle-income economies in meeting SDGs requires targeted efforts to close this gap. EMEs are pivotal in this process, offering substantial contributions toward these goals. To support this argument, I analyzed FDI data from the International Trade Center (2010–2021), presented in Figures 3. This figure shows that emerging economies invest proportionally more in developing economies than developed ones, underscoring the crucial role of EMNEs in investing in regions with low capital accumulation and difficulties attracting economic support from developed economies. Against this background, I outline three primary ways in which EMNEs’ investments in developing economies can advance the SDGs.

EMNEs’ Tech Solutions Overcome Infrastructure Barriers

With their deep knowledge of local markets and frugal innovation capabilities, EMNEs possess a competitive edge in leapfrogging technologies. This allows them to create affordable, tailored products for developing economies, bypassing traditional development stages (e.g., Lashitew, van Tulder, & Muche, 2022). A prime example of this in the context of Africa is M-PESA by Safaricom, which uses SMS technology to make financial services accessible to Kenyans with limited tech exposure at the beginning and significantly expanded financial inclusion across several countries in Africa (Suri & Jack, 2016). M-Pesa laid down a financial infrastructure that acts as a catalyst for further technological and business innovations, such as digital lending platforms and mobile health services. Similarly, Transsion Holdings, a Chinese multinational, has become a leading mobile company in Africa by offering affordable, locally produced and adapted technologies, such as solar-powered chargers and text-to-speech apps, tailored to user needs (Dong, 2022). This local production and customization encourage the growth of related industries, including component manufacturing, software development, and maintenance business.

The case of Transsion Holdings and M-Pesa demonstrates how EMNEs play pivotal roles in advancing SDGs. These enterprises not only foster industry innovation, and infrastructure development but also propel the innovative use of technology in addressing market-specific challenges (SDG 9) and spur entrepreneurial activities. This enhances the industrial base of the economies they operate in and advances economic growth (SDG 8).

EMNEs Provide Job Opportunities for Unskilled and Semi-skilled Workforce

One key competitive advantage of EMNEs is their ability to produce affordable products by leveraging the abundant workforce in their home countries (Ramamurti, 2009). As the labor cost soars, they are relocating their businesses to developing economies. Recently, we have seen significant manufacturing relocations from China, South Korea, and Vietnam to countries such as Bangladesh, Myanmar, Indonesia, and Ethiopia. By tapping into the unskilled and less skilled labor pools, EMNEs help alleviate poverty by providing job opportunities and improving living standards. For example, Dangote Cement, a Nigerian multinational, operates in over 10 African countries by using locally sourced materials to produce affordable cement while creating jobs for less skilled and semi-skilled workers. Similarly, Jiangsu Sunshine Group, a Chinese multinational in Ethiopia, leverages local materials in its textile production and provides employment to tens of thousands of low- and semi-skilled workers, contributing to poverty reduction.

The operations of EMNEs like Dangote Cement and Jiangsu Sunshine Group help eradicate poverty (SDG 1) by providing job opportunities to largely unemployed youth with limited skills as well as by particularly reducing the proportion of people under the poverty line. Besides, by setting up manufacturing facilities in economically marginalized regions and employing local labor forces, these enterprises contribute to leveling economic disparities (SDG 10). Given that the countries in which these multinationals establish their operations are not the prime destinations of MNEs from developed economies, their impact on addressing poverty and reducing inequality can be substantial.

EMNEs Build SMEs’ Capacity and Foster Inclusive Economic Growth

EMNEs uniquely position themselves as strategic partners for SMEs in the global value chain by leveraging their vast experience on market dynamics and consumer preferences both regionally and globally (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra & Pananond, 2023). They enhance SMEs internationalization through their robust networks, market presence, and cost-effective logistics, mostly in the global south, as seen in Asia’s electronics, automotive, and textile sectors. Moreover, EMNEs help SMEs expand their global presence through support in market intelligence, finance, and logistics, including guidance on navigating international regulations. A notable example is Jumia, Africa’s leading e-commerce platform, which has revolutionized market access for thousands of African SMEs. By offering a digital marketplace, Jumia enables SMEs to reach a wide range of domestic and regional consumers, breaking down traditional barriers to market entry. Additionally, Jumia provides crucial logistics support through its extensive delivery network, allowing SMEs to efficiently ship products across regions. This not only enhances SMEs’ ability to compete in broader markets but also provides customers with choices. Although Jumia is not on the same level as Alibaba or Amazon globally, it is an EMNE that has successfully penetrated the African market, whereas Alibaba and Amazon lag in this region.

EMNEs play a critical role in supporting SMEs, significantly contributing to SDG 8 (economic growth) and 10 (reducing inequalities). SMEs act as vital entrepreneurial and employment hubs (Ayyagari, Demirguc-Kunt, & Maksimovic, 2014), often owned and operated by diverse and at times marginalized groups. Through collaboration, EMNEs provide SMEs with crucial access to markets, finance, and technology. This support cultivates an inclusive economic growth ecosystem, ensuring that development benefits are widely disseminated, thereby reaching diverse societal segments. Such strategic alliances are essential for economic growth and leveling up economic disparities in developing regions (SDG 8 & 10).

Recommendations for Stakeholders to Boost EMNEs’ Contribution to SDGs

From the previous discussion, it is evident that EMNEs have clear economic motives to invest in developing economies more than MNEs. Their home country experience and capabilities, such as cost efficiency, handling institutional uncertainty, and networking with key actors including governments, enable them to thrive in developing host countries. However, the low transparency of government and firm interactions in these economies (Birhanu & Wezel, 2022), along with exposure to lower social and environmental standards in their business practices, may lead EMNEs to perpetuate bad practices related to human rights, labor rights and wages, corruption, and environmental protection in host countries (Tashman, Marano, & Kostova, 2019). Therefore, stakeholders must engage EMEs to disclose SDG-related activities, assess their impact, and incentivize them with policy measures to help developing economies achieve SDGs. Below, I outline actionable steps that stakeholders can take to harness the potential of EMNEs in advancing these SDGs.

Driving EMNEs’ Impact on SDGs by Enabling and Persuading ESG Reporting

While EMNEs can provide job opportunities and integrate SMEs into regional/global value chains, ensuring fair wages, protection of human rights, and adequate working conditions, along with equitable value distribution among local actors (employees and SMEs) with respect to EMNEs, is critical. These considerations do not always align with the primary motivations behind EMNE investments in these economies, which are often driven by cost sensitivity. This business model prioritizes cost reduction strategies—such as lower wages, unpaid or underpaid work hours, and cheaper waste management methods—that may compromise standards in working conditions, wage levels, and environmental protection. Consequently, wages can be depressingly low, employees may be mistreated, and depending on the business type, significant environmental pollution can occur.

To address these challenges, the UN Global Compact serves as a pivotal initiative where companies voluntarily report on governance, human rights, labor rights, and environmental issues, which are core for meeting SDGs. Although MNEs typically face stringent ESG disclosure requirements, EMNEs often do not. For EMNEs, participation in the Global Compact can be a key enabler, allowing host countries to better assess the impacts of EMNEs on the economy, people, and environment. This is increasingly relevant because the UN Global Compact now insists on verification for all SDG claims, making window dressing extremely challenging. Moreover, the UN Global Compact, along with allied organizations, can significantly boost EMNEs’ SDG impact by persuading them of the benefits of SDG engagement, such as building trust and reducing regulatory risks, and by enabling them in areas like reporting, data gathering, and standardization. This strengthens EMNEs’ commitment to and contribution towards the SDGs as they thrive in these economies.

Government Policy to Enhance EMNEs’ Role in Supporting SMEs

Governments and development partners can enhance the role of EMNEs in SDGs through targeted policies that make SMEs benefit from the presence of EMNEs (Alvstam, Ivarsson, & Petersen, 2019). This can be achieved by making SMEs attractive business partners and by providing incentives for EMNEs.

For instance, industrial policies and capacity building for SMEs can play an important role here. Industrial zoning can create clusters that enable SMEs to access shared resources, infrastructure, and proximity to EMNEs, fostering collaboration and market access. Capacity building in product standardization, skill upgrading both in production and packaging, as well as networking and creating associations, makes them appealing to EMNEs. EMNEs can approach SMEs as entry points for accessing raw materials, semi-processed, or finished goods for export, or to tap into marketing and distribution networks as they aim to scale up their regional/global presence. They become attractive to EMNEs for integration into their value chains and for fostering the use of leapfrogging technologies.

Governments can also offer incentives for MNEs to integrate SMEs into their value chains, ensuring that local businesses receive a fair share of the value generated. These policies not only help SMEs scale and thrive but also ensure that the benefits of growth are distributed equitably, directly contributing to SDG 8 by creating jobs and driving sustainable growth and SDG 10 by reducing inequalities through inclusive economic opportunities.

Enhancing EMNEs’ Role in SDGs Through Leapfrogging Technology Policies

Governments can enhance the role of EMNEs in advancing SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by implementing policies that promote leapfrogging technologies. EMNEs, with their ability to innovate and tailor affordable solutions, can bypass traditional infrastructure development stages. For example, technologies like M-PESA have revolutionized access to financial services, while other EMNEs, like Chinese companies offering mobile tech solutions, address key infrastructure gaps in energy, communications, and finance.

Governments can create policies and incentives that encourage EMNEs to introduce these leapfrogging technologies, which can drive technological innovation and infrastructure development at a local and regional level. These innovations not only enhance infrastructure but also stimulate entrepreneurship and economic growth by opening new market opportunities, creating jobs, and fostering the development of new industries, all of which directly contribute to SDG 8 and SDG 9.

I summarize the key points made in points 2 and 3 by highlighting selected competitive strategies of EMNEs and their alignment with specific SDGs, along with policy recommendations designed to enhance their impact on these targeted goals in Table 1.

Conclusion

Previous studies examined how MNEs can help advance UN sustainable goals (e.g., Dau et al., 2023). In this paper I argue the unique roles of EMNEs in advancing SDGs in developing economies. This is particularly important at this juncture, where developing economies are lagging far behind in meeting SDGs, and economic support from developed economies is becoming scarcer. Through their tailored product offerings, engagement with local SMEs, and employment of the local workforce, EMNEs directly address the challenges and needs unique to these economies. Their involvement has a paramount potential to go beyond mere business expansion, embodying a strategic contribution to critical areas such as poverty alleviation, economic development, and sustainable innovation. By focusing on the nuanced demands of developing economies and leveraging local resources and capabilities, EMNEs not only succeed in their business endeavors but also play a pivotal role in closing the significant SDG achievement gap found in these regions. Their actions and transformative potential require the support and effort of key stakeholders to push EMNEs to align their business objectives with sustainable development goals. The sustainability goals EMNEs can impact, and the extent of that impact, vary by industry and company characteristics. For example, labor-intensive MNEs like Jiangsu Sunshine Group or Dangote Cement can significantly contribute to SDG 1 (No Poverty) by creating jobs for those below the poverty line. In contrast, platform companies like Jumia, a leading pan-African e-commerce platform, can impact SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by addressing infrastructure challenges and driving innovation.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to editor William Newburry and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback, and to the participants and organizers of the AIB Insights Paper Development Workshop in Nairobi for their valuable contributions. Special thanks to emlyon business school for sponsoring my trip to Kenya.

About the Authors

Addis Gedefaw Birhanu is associate professor of Strategy and Organization at EMLYON Business School, France. She completed her Ph.D. in Business Administration and Management from Bocconi University, Italy. Her research interests are in the nexus of non-market strategy and, corporate governance, and their implications on firm performance. Her research has been published among others in Strategic Management Journal, Strategic Organization, and Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. Addis currently serves as a member of the Editorial Review Board of Strategic Management and the Academy of Africa Journal.