Introduction

Geopolitical tensions are becoming the new normal in the current international business (IB) landscape, as evidenced by the Tech Cold War[1] between the US and China. Geopolitics examines how geographic, political, and economic factors influence international relations and global power dynamics. In this context, nonmarket actors such as governments and the news media arguably impact MNEs substantially. In particular, media coverage can crucially influence public perceptions of corporate legitimacy. For example, during the Tech Cold War, media coverage often framed Chinese tech companies like Huawei as potential threats to national security, creating legitimacy challenges for these firms in Western markets (Li & Sun, 2020; Zhang, Xu, & Robson, 2023). Similarly, TikTok faced intense scrutiny in the US, with media narratives emphasizing data privacy concerns and geopolitical risks. These examples illustrate how media coverage can shape public perceptions of MNEs, making it a critical factor for firms navigating geopolitical tensions.

Beyond media coverage, the media’s role extends to influencing public and government sentiments for MNEs. For example, the media can play an important role in wartime by disseminating political propaganda. Because periods of geopolitical tension (e.g., the Tech Cold War) resemble wartime to some extent, the media’s role cannot be ignored in this context. Moreover, maintaining a “free market” of information exchange in the media is challenging due to manipulation by the government and special interest groups. During the US-China trade dispute from 2013 to 2020, the news media actively used strategy framing, which emphasized zero-sum national competition and predicted the win-lose outcomes, thereby “uniting and engaging domestic populations, thus promoting patriotism and support for one’s own leaders” (Liu, Boukes, & De Swert, 2023: 978). Therefore, it is important for MNEs to consider their media engagement and media strategies under geopolitical tensions.

When facing geopolitical tensions, MNEs can adopt nonmarket strategies such as corporate diplomacy and IB diplomacy to overcome challenges (Sun, Doh, Rajwani, & Siegel, 2021). However, the current strategies emphasize the business‒government relationship, neglecting other stakeholders such as the media. Scholars recommended that MNEs should pay more attention to legitimacy-granting actors beyond governments (Stevens, Xie, & Peng, 2016). With nonmarket actors proliferating in the global economy through forms of techno-nationalism and protectionism, MNEs can integrate media strategies into their nonmarket strategy to navigate legitimacy challenges under geopolitical tensions. This article, therefore, explores how MNEs can develop media strategies to navigate geopolitical tensions arising from conflicts between their home and host countries.

Four Geopolitical Dynamics in Media Coverage of MNEs

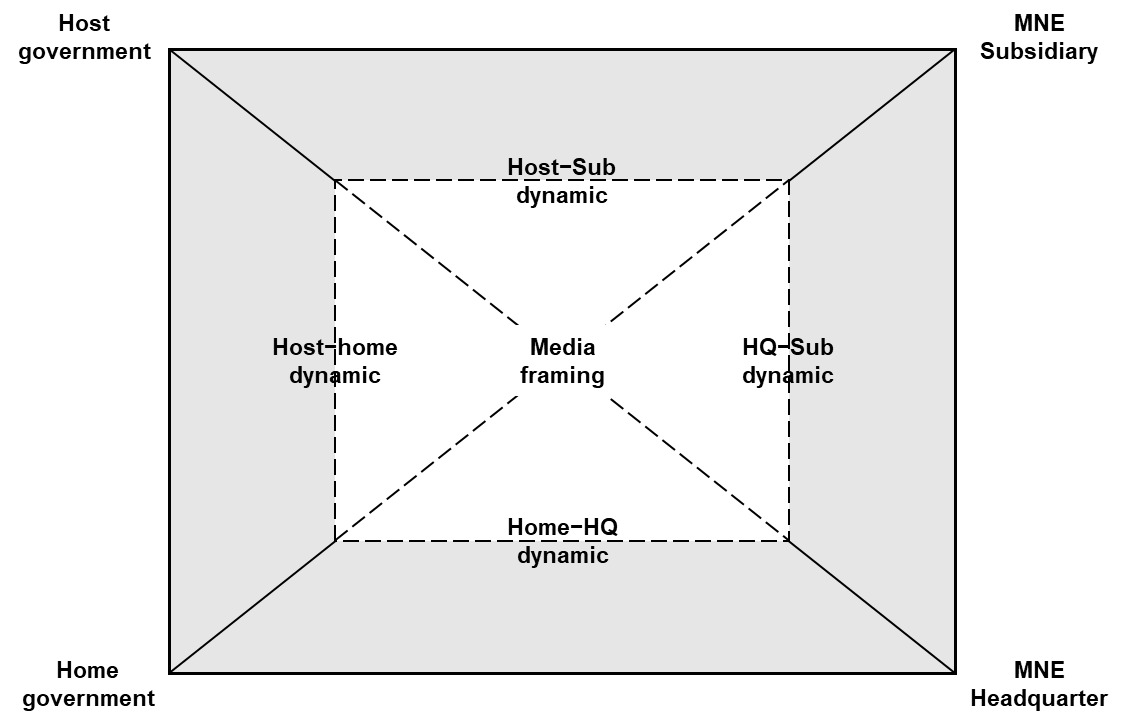

A typical challenge for MNEs navigating geopolitical tensions is the political pressures exerted by their home and host countries. Business stories involving geopolitical rivalry are more newsworthy, increasing the media coverage of MNEs. Media studies scholars have long used media framing[2] to unpack the role of the media in shaping public perception, for example, through problem definition, causal attribution, moral evaluation, and treatment recommendation (Entman, 1993). Under geopolitical tensions, media framing can reflect political agendas, posing political and public legitimacy challenges for MNEs. Therefore, MNEs need a comprehensive understanding of their media coverage to navigate media-related challenges, which include four geopolitical dynamics (see Figure 1). These dynamics are contextualized within geopolitical tensions, as illustrated by the case of Trump’s TikTok ban.[3]

The Host−Home Government (Host–Home) Dynamic

The Host–Home dynamic refers to media coverage of MNEs’ dual political sentiments when relations between the home and host countries deteriorate. In democratic countries, the news media is often seen as the “fourth estate,” independent of the state and prioritizing the public interest. However, even in democracies, the news media may exhibit political bias, especially during geopolitical competition, when national interests are at stake. In authoritarian regimes, the news media is often part of the state apparatus and propagates the state’s interests.

The US government banned TikTok, citing national security concerns linked to potential Chinese government access to user data. The US media framed TikTok’s Chinese ownership as a potential national security threat because the app collected data on American users. For example, The New York Times reported: “Whether it’s TikTok or any of the other Chinese communications platforms, apps, infrastructure, this administration has taken seriously the requirement to protect the American people from having their information end up in the hands of the Chinese Communist Party” (Kang, Jakes, Swanson, & McCabe, 2020). Conversely, the Chinese media portrayed the US actions as an attempt to stifle competition and maintain technological hegemony. For example, the Chinese state media publication Global Times reported: “The Chinese government on Tuesday warned the US of ‘consequences’ if it opens the ‘Pandora’s Box’ with what a Chinese official called ‘political manipulation’ and a crackdown on a Chinese company” (Wang, 2020). This dynamic indicates the dual political pressures TikTok faced from the US and Chinese governments in media coverage.

The Host Government−MNE Subsidiary (Host–Sub) Dynamic

The Host–Sub dynamic refers to the challenges MNEs face in managing relationships with host governments and their subsidiaries during periods of geopolitical tension. A key aspect of this dynamic is liabilities of origin, where MNEs face legitimacy challenges stemming from their nationality, not their foreignness. For example, in the TikTok case, the US government feared that the Chinese government could access user data. Such geopolitical tensions are newsworthy for the local media. Indeed, the US media has played the role of both sense-maker and sense-giver, framing TikTok as a potential espionage tool. Therefore, MNEs must navigate both political pressure from the host government and public pressure shaped by the media. TikTok, a subsidiary of the Chinese company ByteDance, had to communicate directly with the US government to address data privacy concerns. The company also publicly stated that it had never provided user data to the Chinese government. In addition to direct engagement with the US government, TikTok actively leveraged its user base—TikTokers—to fight against Trump’s executive order. TikTokers, many of whom were young and highly engaged, became a powerful force in shaping public opinion. By winning support from TikTokers, TikTok was able to use media to make voices for its grassroots users, countering the negative framing by the US government and the hostile media. The Host-Sub dynamic, therefore, encompasses media framing, direct government-subsidiary interactions, and seeking public support through the media for MNEs to navigate legitimacy challenges under geopolitical tensions.

The Home Government−MNE Headquarters (Home–HQ) Dynamic

The Home–HQ dynamic highlights how MNEs respond to political pressures from their home government, especially when the domestic media shapes nationalistic narratives and urges MNEs to uphold national interests. During periods of geopolitical tension, home governments often expect MNEs to support national agendas, and the media plays a crucial role in communicating these expectations. In the TikTok case, the Chinese government viewed the US actions against TikTok as part of a broader strategy to undermine China’s technological advancements and economic interests. For example, China’s South China Morning Post quoted a Chinese official as stating: “ByteDance shouldn’t surrender without a fight” (Xin, Qu, & Lo, 2020). In response, ByteDance communicated through the media that “it had applied for a technology export license to comply with China’s recently revised tech export rules” (Qu, 2020). This demonstrates how MNEs can use the media to signal compliance with home governments’ expectations and navigate geopolitical risks. By leveraging the domestic media, MNEs can build public support and strengthen their relationship with their home government, which is crucial for countering the pressures exerted by host governments.

The MNE Headquarters−Subsidiary (HQ–Sub) Dynamic

The HQ–Sub dynamic emphasizes that MNEs need to develop a coherent media strategy when facing political pressures from various countries. This dynamic focuses on how the headquarters and subsidiaries coordinate their responses to divergent media narratives in diverse political environments. In the TikTok case, ByteDance had to devise a media strategy that addressed the divergent narratives in the US and China. In the US, ByteDance needed to mitigate concerns about data privacy and national security, whereas in China, it had to support the narrative of resisting US protectionism and maintaining technological sovereignty. This dynamic illustrates the challenge for TikTok in crafting a consistent global message that resonates with diverse audiences while addressing the specific demands of diverse political environments. Thus, one of the key challenges in the HQ–Sub dynamic is ensuring effective communication and alignment between the headquarters and subsidiaries. The headquarters must provide clear guidance and support to subsidiaries, while also allowing them the flexibility to adapt to local media and political contexts. Misalignment between HQ and Sub can lead to inconsistent messaging, which may undermine the MNE’s legitimacy in both countries. Therefore, MNEs must strike a delicate balance between responding to the demands of the home government and addressing the concerns raised by the host country’s media framing.

A Framework for MNEs’ Media Strategies Under Geopolitical Tensions

This article proposes a framework (see Figure 2) for MNEs to develop media strategies when tensions arise between their home and host countries. Although geopolitical tensions can also emerge from conflicts between other countries (Meyer, Fang, Panibratov, Peng, & Gaur, 2023),[4] this framework focuses on the pressures MNEs face due to conflicts between their home and host countries, a situation that presents unique legitimacy and communication challenges.

The dashed box “Geopolitical tensions” demonstrates how MNEs face legitimacy pressures from both home and host countries. Such pressures can be further framed by the media and transmitted to MNEs. Two pairs of contestations might operate in this context: the first pair is the geopolitical rivalry between MNEs’ home and host countries, and the second pair is the interplay between MNEs’ home media and host media. The dashed box “MNEs’ media strategies” indicates firm-level communication practices to counter government- and media-generated political pressures. Echoing the abovementioned four dynamics, MNEs’ media strategies could encompass the following four interrelated aspects.

Contextual Adaptation to Geopolitical Sentiments

The Host–Sub dynamic highlights the need for MNEs to adapt to their host countries’ geopolitical sentiments. MNEs can use media engagement, developing strategies integrating corporate diplomacy and political lobbying to respond to host-government- and media-generated legitimacy challenges (Doh, Dahan, & Casario, 2022). Contextual adaptation requires MNEs to keep monitoring and tracking local media coverage and public sentiment. This keeps MNEs informed about emerging issues and trends that may impact their operations. In response, MNEs can issue press releases, give interviews, and organize press conferences to highlight their local economic and social contributions, thereby improving their corporate image. MNEs facing negative media coverage or crises should promptly respond to media inquiries, provide clarifications, and address misinformation to protect their reputation. In addition, MNEs can use media engagement to build emotional connections with users, customers, and the public, especially when the protectionism and populism in the host country are against the public interest. By building emotional connections through media engagement, MNEs can strengthen their legitimacy and foster goodwill among local stakeholders, even in the face of geopolitical tensions.

Strategic Alignment with Nationalistic Narratives

The Home–HQ dynamic emphasizes the need for MNEs to align their communication with national interests. MNEs can use the media to show their commitment to national interests under geopolitical tensions, preventing public backlash and maintaining legitimacy in the eyes of home governments and the public. Through media communication—e.g., by preparing key messages, appointing spokespersons, and responding quickly to media coverage—MNEs can maintain good relationships with government agencies. However, proactive alignment with state-owned media might damage MNEs’ relationship with host governments under geopolitical tensions. In such situations MNEs can adopt a dual-track approach: In the home country, they can leverage influencers, experts, and think tanks to speak for them in the media, thereby demonstrating alignment with national interests and fostering a sense of patriotism among stakeholders. In the host country, they can focus on emphasizing their contributions to the local economy and society, while avoiding overt alignment with the home country’s nationalistic narratives. This balanced approach helps MNEs maintain legitimacy in both home and host countries without exacerbating tensions.

Global Media Engagement and Agility

The Host−Home dynamic underscores the importance of global media engagement and agility, which involves developing a flexible media strategy that balances standardized global messaging with localized adaptations. A global media strategy does not imply a one-size-fits-all approach; rather, it requires MNEs to tailor their communication to address local challenges while maintaining a coherent global narrative. Agility involves making trade-offs between strategic alignment in the home country and contextual adaptation in the host country, thereby reconciling contradictory political sentiments when geopolitical tensions are rising. Although global media engagement is often necessary, sometimes a non-engagement strategy may be appropriate. For instance, in authoritarian regimes where the media is tightly controlled by the state, media engagement may risk aligning the MNE with one side of a political conflict, exacerbating tensions. In such cases, MNEs can adopt a low-profile approach, avoiding public statements and focusing on behind-the-scenes diplomacy or direct engagement with government officials. This non-engagement strategy can help MNEs avoid unnecessary scrutiny and maintain operational flexibility in highly politicized IB environments.

Organizational Design and Collaboration

The HQ–Sub dynamic indicates the need for MNEs to optimize their internal structure and organizational design to formulate effective media strategies. This involves building a diversified communication team, fostering interdepartmental collaboration, and potentially partnering with public/government relations agencies to navigate adverse IB environments. Interdepartmental collaboration ensures that diverse organizational perspectives are integrated into the media strategy, enhancing its effectiveness. For example, MNEs’ public relations department can collaborate with government relations department on developing media strategies which can better take political sentiments into consideration. In addition, MNEs can partner with public relations and government relations agencies with expertise in navigating complex political and media landscapes, which can provide valuable insights, strategic advice, and support in managing media relations.

Challenges and Costs for MNEs’ Media Strategies

MNEs’ media strategies are neither easy nor costless, as firms must navigate the complexities of balancing the four geopolitical dynamics. Several challenges demand careful attention. One major challenge is the conflicting demands of home and host governments, while another is the divergent media narratives in different countries. Firstly, even when adopting a dual-track media strategy, MNEs may find themselves unable to fully satisfy either the home or host country, making it difficult to maintain a neutral position. As a result, MNEs risk facing regulatory restrictions and legitimacy damage in both markets. Secondly, a dual-track media strategy can lead to inconsistent messaging, undermining the MNE’s integrity and reputation in both home and host countries. This inconsistency can be particularly challenging for MNEs that prefer to adopt a centralized communication team, as it requires balancing global coherence with local adaptability. In situations where MNEs realize they cannot fully balance all the dynamics under geopolitical tensions, they may have to make strategic trade-offs to minimize the negative impact from both governments and the media. These trade-offs often involve prioritizing certain markets or stakeholders while accepting partial success in others.

Huawei’s experience in Five Eyes countries (the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) versus other Western countries (e.g., Germany, France) provides a clear example of partial success in balancing the four dynamics. In Five Eyes countries, where the debate of “decoupling from China” dominated the media arena, despite Huawei’s efforts to address these concerns—such as opening transparency centres and offering to sign no-spy agreements—it was unable to fully overcome the negative media framing and political pressure. In contrast, in other Western countries where the media narratives focused more on “de-risking from China”, Huawei had more room for adapting its media strategy to ease the geopolitical tensions. The partial or full success of MNEs’ media strategies would depend on how companies can understand the dynamic conditions of geopolitical tensions surrounding them. Ultimately, MNEs’ media strategies must be integrated into their broader nonmarket strategies, which encompass wider considerations of business-media-government relationships, and must be part of a holistic approach that includes corporate diplomacy, political lobbying, and stakeholder engagement (Doh et al., 2022).

Conclusion

MNEs can use nonmarket strategies to mitigate negative impacts in an adverse IB environment, with media strategies constituting an important part of this toolkit. To develop media strategies under geopolitical tensions, MNEs need to take into consideration the geopolitical dynamics of relationships between nations. Trump’s TikTok ban offers an insightful lens for understanding these dynamics. Using this lens, this article highlights four dimensions of MNEs’ media strategies: contextual adaptation to geopolitical sentiments, strategic alignment with nationalistic narratives, global media engagement and agility, and organizational design and collaboration. The proposed framework offers guidance to MNEs on navigating media-related legitimacy challenges under geopolitical tensions. Future studies could also explore how MNEs can develop media strategies in response to geopolitical tensions involving multiple countries, which have more complicated effects on global business.

About the Author

Anlan Zhang is Senior Lecturer at the Lee Shau Kee School of Business and Administration, Hong Kong Metropolitan University. He obtained PhD degree from Cardiff University, where he also held MBA and MSc (Social Science Research Methods). His research interests focus on international business, corporate media coverage and nonmarket strategies, with an interdisciplinary focus. Before joining academia, Anlan had rich working experience in finance and media industry in China.

The term “Tech Cold War” refers to “a state of antagonistic geopolitical rivalry between the superpowers along multiple fronts for achieving supremacy over technologies of crucial importance for national security as well as human development” (Tung, Zander, & Fang, 2023).

The term “media framing” is closely linked with traditional or established media, which usually applies a standardized procedure in news production. Thus, social media platforms, which mostly rely on user-generated content, are not the focus of this article.

In 2020, US President Donald Trump ordered the Chinese company ByteDance to divest ownership of its popular video-sharing app TikTok, citing national security concerns over data collection and potential access by the Chinese government. This led to a series of executive orders, legal battles, and negotiations involving major US companies as well as the implementation of new export control regulations by the Chinese government. Ultimately, the ban was temporarily blocked by a US judge, and the issue received less public attention after Trump left office.

Although this article focuses on geopolitical tensions between home and host countries, MNEs can also be affected by conflicts between other countries. For example, the Russia–Ukraine conflict has had widespread implications for global supply chains, energy markets, and multinational operations, even for MNEs not directly based in or operating in these countries. However, such scenarios often involve different dynamics and require a separate analysis.