Introduction

I am at that stage in my career where I am facing a dual penalty because I am a woman and I speak with an accent. I am fluent in four languages, yet my leadership skills are questioned because of my accent… Apparently, I sound too low-class, so now guess what happens when my low-class speech interacts with my gender? I no longer get considered for promotions.

– A woman senior manager at a leading consulting firm in the USA

Imagine you have worked hard towards a leadership position within your multinational company (MNC) only to be brought to a halt not because of your lack of intelligence or skills, but simply because of your gender and the way you speak. In this article, we provide recommendations on how practitioners can limit the potential for epistemic injustice linked to women with non-native accents by drawing from the glass ceiling phenomenon and the concept of epistemic injustice.

Prior research suggests that non-native speakers of the corporate language (both men and women) can experience ‘language penalties’ that could hinder their career progression and lower their perceived status within MNCs (Wilmot, 2024). However, by interviewing 15 leaders in MNCs in India and the USA, we found that, within our sample, women leaders described penalties related to their accents that were largely missing from the men’s accounts. Men and women in our study had vastly different experiences with their accents; several women identified their non-native accents as a key attribute that hindered their progression into the C-suite. For example, a woman senior manager said:

I often find that people in this organization question my intelligence because of the way I speak. I realize I have a strong accent when I speak English, but this does not mean I am not smart! Career progression is already challenging for a woman but how can I get promoted when others consider me less smart than those [i.e. men] who don’t speak with an American accent?

When asked, men did not perceive their non-native accents to be a hindrance as indicated, for example, in the following response of a male managing partner:

I am proficient in the corporate language [English] and I have been working here for almost a decade. As you know, I am not a native English speaker, but my accent has never hindered my career.

This is an intriguing difference, which we explore through the lens of intersectionality, an analytical framework to understand how the combination of individuals’ social identities results in unique experiences of discrimination (Crenshaw, 1991). We propose that practitioners should pay attention to potential epistemic injustices. The theory of epistemic injustice acknowledges that women with accents can be knowledgeable and adequate leaders, but biases result in undermining their competencies, ultimately limiting MNCs’ goal to hire and promote based on merit.

Epistemic Injustice and Women with Non-Native Accents

Epistemic injustice has its roots in feminist philosophy. It refers to the harm individuals can experience as knowers due to the judgment of others, explaining practices of exclusion, silencing, and undervaluing one’s potential to add value (Fricker, 2007; Wilmot, 2024). Epistemic injustice is about unfairness in how people are treated when it comes to knowledge; how they share it, how they are believed, or how they contribute to conversations (Fricker, 2007). This can lead to prejudicial judgments of social identities (Muzanenhamo & Chowdhury, 2023). This injustice often manifests as testimonial injustice on the individual level, where one’s credibility is unfairly diminished based on prejudices about personal characteristics such as accent bias. An example of testimonial injustice is when a woman leader with a non-native accent presents an idea in the boardroom only for it to be dismissed; yet, when a man presents the same idea, it is taken seriously. The second form of epistemic injustice is hermeneutical injustice at the societal level, where a lack of shared language makes it difficult to understand and express the injustices faced by certain groups of people due to their historic exclusion. Fricker (2007) uses the example of ‘sexual harassment’ which, upon introducing the term, eased women’s difficulties in expressing their experiences. She states that this difficulty was due to the exclusion of women in shaping the English language and participating in professions that help explain social phenomena. Epistemic injustice is therefore useful to shed light on the processes of discrimination against a person based on their perceived knowledge. In our case, when a woman who speaks with an accent suffers from a credibility deficit due to prejudices associated with her identity, she is harmed in her capacity as a knowledgeable leader.

It is important to acknowledge the role privilege and supremacy play in accents, which make some accents less accepted than others due to colonialism and historical oppression (Crenshaw, 1991). Importantly, we must acknowledge that such injustices are not just individual disadvantages. They are created and sustained by institutions and norms that encourage and reward such behavior. Structural inequalities often lead individuals to make judgments about which accents are associated with lower classes and uneducated populations, thereby leading to assumptions that harm women who speak with non-native accents in their capacity as knowers (Wilmot, 2024).

Women leaders are perceived differently than their male counterparts due to gender bias, but women leaders with accents also differ from their fellow women competitors who do not have an accent (Hideg, Hancock, & Shen, 2023). These compounded biases, while often unconscious, devalue skills and lower the potential value added to the organization/team, leading to denied access to leadership positions although these women would otherwise meet the criteria to become a leader. While there are exceptions (e.g., former CEO of PepsiCo Indra Nooyi), these are rare; ultimately, for example in Canada, there are still more corporate CEOs named Michael than corporate women CEOs (Saldanha, 2023).

The glass ceiling is the effect of bias as well as structural and cultural barriers that prevent women from reaching C-suite positions (Hull & Umansky, 1997). Non-native accents add another layer to these barriers, and our goal is to explain the cross-cutting element as a form of epistemic injustice. A better understanding of how to limit epistemic injustice is not only important for economic but also for moral reasons (Fitzsimmons, Özbilgin, Thomas, & Nkomo, 2023).

Suggestions for MNCs

MNCs have unique characteristics because their workforce is naturally more diverse and international than domestic firms. Hence, non-native accents are more common. While some people may be more used to non-native accents, it also increases the chances of employees working with someone who speaks with a non-native accent. This gives employees motive, means, and an opportunity to discriminate against their accented peers due to conscious or unconscious biases.

Biases resulting from epistemic injustice are often invisible and require awareness from everyone involved. Yet, research suggests that for women leaders, accents were particularly impactful for how they felt colleagues perceived them (Liu, 2023). We dare management to explore the realities of epistemic injustices (including both individual-level and structural or group-level injustices) and to actively look for their unconscious prejudices that lead to injustices for women with non-native accents. To do this, we suggest an intersectional approach to reduce injustices by considering both gender and language. The following are recommendations for actions that MNCs can take to reduce epistemic injustice for women with non-native accents.

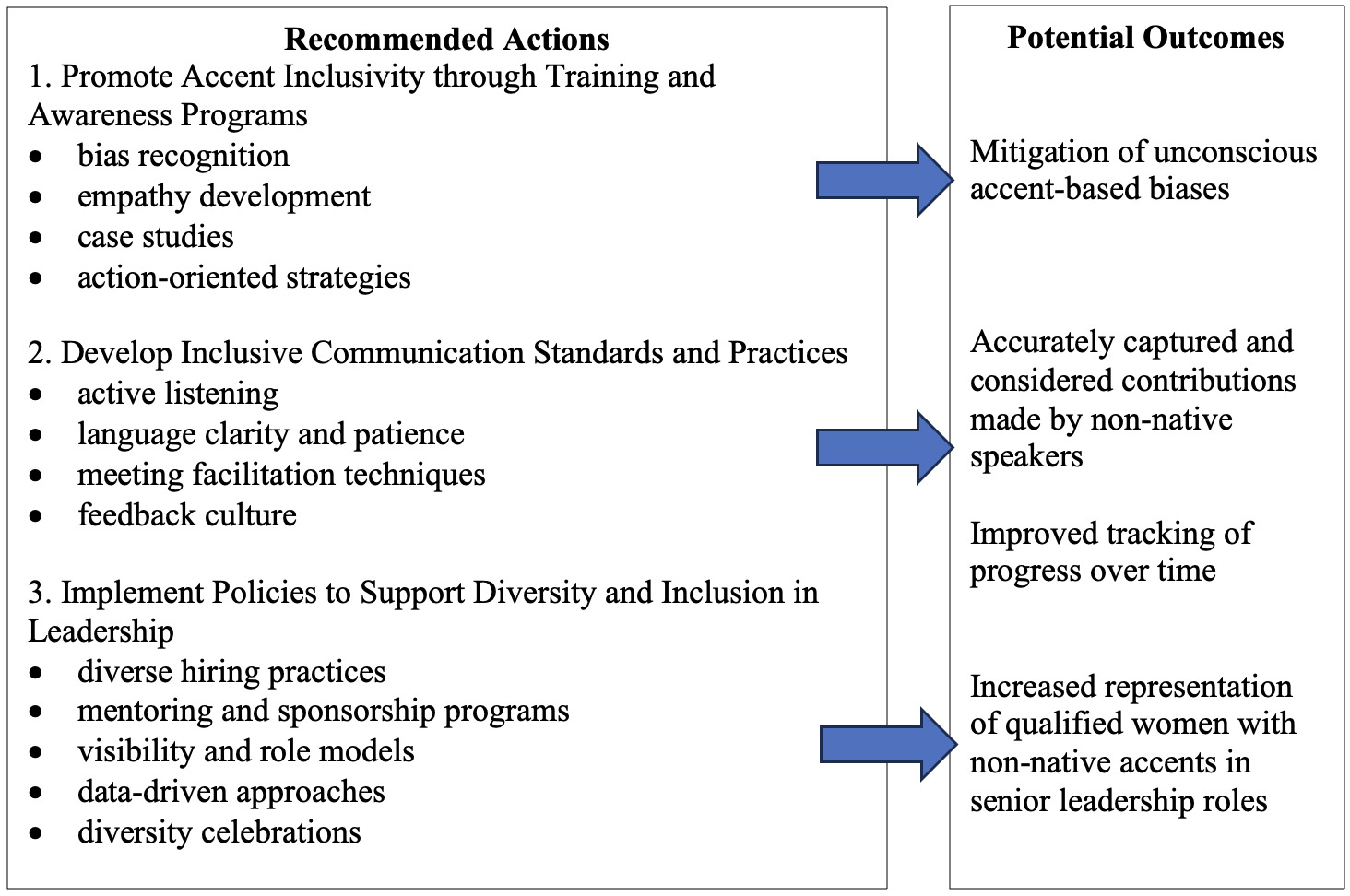

1. Promote Accent Inclusivity through Training and Awareness Programs

Accent inclusivity training can go beyond mere awareness of individuals in an MNC speaking with non-native accents. Instead, it can create an opportunity for employees to delve into the cognitive and social biases that underpin accent prejudice. Adding examples of testimonial and hermeneutical injustice, such as those we provided above, to existing training programs can be a first step to counteract accent bias; this involves educating employees about the unconscious bias that often occurs when people perceive accents as a marker of intelligence, credibility, or professionalism. The extent to which this unconscious bias exists depends on the makeup of the MNC. If non-native speakers are represented in management, this bias may be less prevalent. However, MNCs should incorporate accent bias into training within diversity and inclusion initiatives to help employees understand how biases related to gender, accent, race, and other factors can intersect and heighten prejudices and, as a result, discrimination. Training should include (1) bias recognition, (2) empathy development, (3) recent case studies, and (4) continuously updated action-oriented strategies.

Testimonial injustice occurs when individuals with non-native accents are perceived as less credible, impacting their ability to contribute meaningfully (Fricker, 2007). This is particularly relevant if employees with non-native accents are not represented in important roles within the MNC. Since MNCs have an on average more international workforce, they should be more prone to have employees with non-native accents in leadership roles than domestic firms. Training can help employees recognize and challenge their biases regarding accents to understand how these affect judgments and decision-making in the workplace. Empathy-building exercises can mitigate testimonial injustice by allowing employees to experience the challenges faced by those with non-native accents. Such experiences can help shift perceptions and foster a more equitable evaluation of contributions. The use of interactive activities such as role-playing or listening exercises can foster empathy and understanding. For example, simulations where employees experience speaking in a non-native accent can help them understand the challenges their colleagues face. Sharing case studies and examples from within the organization (anonymized if necessary) or from other companies can illustrate the real impacts of accent bias on career progression and employee morale (Lev-Ari & Keysar, 2010). Equipping employees with practical strategies can counteract bias, such as actively listening to content over accent, and fostering a mindset that values diverse perspectives. This approach aligns with Fricker’s (2007) concept of rectifying epistemic injustice by promoting a focus on deep level rather than superficial markers.

Despite these predictions, there are potential challenges when promoting accent inclusivity through training and awareness programs. For instance, in a multicultural environment such as an MNC, there are many diversity characteristics and combinations of them. It may be overwhelming for employees to take them all in. When discussing these characteristics, training and awareness programs also point out these differences to employees who had not recognized them before the training, potentially reinforcing epistemic injustice. Additionally, it is difficult to measure the impact of these programs on biases. As a result, the implementation of such programs in MNCs should always go hand in hand with additional actions such as inclusive hiring and communication standards, as discussed in the following sections.

When accent and gender bias are effectively discussed in training and awareness programs, we expect that promotion decisions will actively mitigate unconscious biases against women with non-native accents, ultimately increasing their representation in senior leadership positions.

2. Develop Inclusive Communication Standards and Practices

Inclusive communication standards aim to create a work environment where all voices are heard and respected, regardless of accent or language proficiency. This includes (1) active listening, (2) language clarity and patience, (3) meeting facilitation techniques, and (4) a feedback culture. This is particularly important in a multilingual environment such as an MNC.

Training employees in active listening techniques, such as giving full attention to the speaker, not interrupting, and summarizing what was said to confirm understanding can reduce the likelihood of miscommunication and helps ensure that all contributions are valued based on their content, thus reducing instances of testimonial injustice (Lev-Ari & Keysar, 2010). Encouraging clear, slow, and deliberate communication, particularly in meetings that consist of individuals from distinct linguistic backgrounds, can help to reduce hermeneutical injustice, i.e., misunderstandings that are incorrectly attributed to a speaker’s accent rather than the complexity of the topic. Because MNCs function across countries, meeting discussions are often complex; clear communication is therefore important for non-native speakers and all employees to enhance efficiency and effectiveness. Implementing structured meeting practices, such as round-robin speaking, can ensure every participant has an opportunity to speak without interruption, thus reducing testimonial and epistemic injustice.

Additionally, technology can be a powerful tool for diminishing accent biases and prejudices. MNCs can use visual aids (like slides or memos), real-time translation, subtitles, and automated meeting transcripts to reduce epistemic injustice and address hermeneutical injustice by ensuring non-native speakers’ participation in discussions. MNCs should encourage a system of feedback for continuous improvement. This might include the establishment of a norm where colleagues are encouraged to respectfully ask for clarification if they do not understand something to normalize such requests and reduce the stigma around accent-related misunderstandings. Another strategy could include the administration of regular anonymous surveys or check-ins to gather employee feedback on experiences related to accent bias and other forms of discrimination.

While implementing inclusive communication practices and standards, managers should consider some potential challenges. For example, employees might not provide honest feedback in check-ins to avoid confrontations. Anonymous feedback forms available to all employees have been found to help with reducing the issue. Tools like real-time translation and automated meeting transcripts often struggle with accuracy, therefore, additional personnel might be required to check the accuracy of the generated notes to ensure that they convey the nuance of the speakers’ messages. Furthermore, employees who are unaware of their biases might be resistant to the use of technology or round-robin speaking. Therefore, these practices should be implemented in combination with change management practices and policies that emphasize inclusive hiring to create a diverse employee pool that can understand the importance of inclusive communication.

The implementation of the abovementioned practices can lead to fewer miscommunications between all employees, more open discussions, and fewer complaints of discriminatory behavior. It also allows for identifying areas for improvement and tracking progress over time.

3. Implement Policies and Practices to Support Diversity and Inclusion in Leadership

Organizational policies should explicitly recognize and aim to mitigate accent bias to tackle the glass ceiling phenomenon and epistemic injustice, particularly in leadership roles. Key actions include (1) diverse hiring practices, (2) mentoring and sponsorship programs, (3) visibility and role models, (4) data-driven approaches, and (5) diversity celebrations.

Including employees on hiring and promotion committees for leadership positions who have lived experience as women with non-native accents and/or are allies for women with non-native accents can ensure that biases are removed. Establishing metrics can ensure diversity in leadership positions, including gender and accent diversity. This might involve setting specific targets or benchmarks for the representation of women with non-native accents in managerial and executive roles, thus correcting testimonial and hermeneutical injustices by ensuring that women with non-native accents are given fair opportunities for advancement. Creating mentorship programs that pair women with non-native accents with senior leaders can provide guidance, support, and advocacy. Sponsorship goes beyond mentorship by actively promoting protégés within the organization, thus opening doors to career-advancing opportunities. Further, MNCs can develop programs that specifically support those at the intersection of multiple biases. For example, networking groups or support circles can provide safe spaces to discuss challenges and share coping strategies. MNCs can increase the visibility of successful women with non-native accents through internal communication channels (e.g., newsletters, leadership panels). This helps to counteract stereotypes and shows that leadership success is not bound to having a native accent. This approach mitigates both forms of epistemic injustice by challenging and reshaping biased perceptions.

MNCs can collect and analyze data on the experiences of women with non-native accents within the organization to identify patterns of bias or exclusion. It is important to follow the principle of “nothing about us without us” in designing data gathering. Women with non-native accents should be integral members and given dedicated time in their workday for such projects to ensure that the process of collecting, analyzing, and sharing data is done in an inclusive manner that encourages women with non-native accents to share their experiences safely and avoids perpetuating biases. This data should inform diversity and inclusion strategies, ensuring they are tailored to the needs of all employees. This would also help MNCs review policies to ensure they do not inadvertently disadvantage individuals based on intersecting identities. This might involve, for example, reassessing performance review criteria to remove ingrained biases. MNCs can formally embrace diversity within the organization through events, workshops, or spotlighting diverse employees. Highlighting different accents as assets rather than hindrances can shift the organizational culture towards greater inclusivity.

Despite the potential for positive impact of these actions, managers should keep some potential challenges in mind. To ensure inclusive approaches, women with non-native accents should be involved in hiring and data generation efforts. However, these risks overburdening women with non-native accents who are already at a disadvantage by adding responsibilities to their jobs. It is therefore a necessity to ensure adequate compensation and/or time allocation to minimize this risk and encourage allyship from others.

When organizational practices actively support and empower women with non-native accents, prejudice and epistemic injustice against them decreases and representation of women with non-native accents in senior leadership roles increases over time. Figure 1 visualizes the recommendations and outcomes.

Conclusion

This article proposes that managers think about potential epistemic injustices in their organization. We pay attention to a specific group – women with non-native accents who possess knowledge that is generally ignored or undervalued by organizations. While managers try to promote based on merit, it is difficult to look at merit objectively when personal attributes such as language are the first point of contact. Managers can reap knowledge from these women by limiting these injustices.

About the Authors

Komal Kalra is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in International Management at the Newcastle University Business School. She is passionate about helping organizations recognize and comprehend the strengths of diversity, particularly in emerging economies. Her aim is to improve the way individuals and organizations cope with diversity, specifically language and gender diversity. Her work has appeared in journals such as the Journal of World Business and Management and Organization Review.

Magdalena Viktora-Jones is an Assistant Professor of Management at the University of Southern Indiana’s Romain College of Business. Her research interests include corporate and country reputation, diversity, equity, and inclusion policy implementation in the domestic and global context, as well as language dynamics in multinational enterprises. Her work has appeared in journals such as the Journal of International Management and Social Forces.

Tomke J Augustin is a Research Associate in the Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba. In her PhD dissertation, she explored the contributions and barriers of multicultural and multilingual employees in multinational work contexts. She now primarily studies equity, diversity and inclusion issues in entrepreneurial ecosystems with the goal to remove systemic barriers to enable equal participation of all demographic groups in innovations. Her work has appeared in journals such as the Journal of Management, Human Relations and Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal.