Introduction

In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith emphasized language’s critical role in international trade. Similarly, a pan-African lingua franca could support the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) in boosting intra-African trade, socio-economic transformation, and poverty reduction. Launched in 2019, AfCFTA—the world’s largest free trade area—encompasses 1.5 billion people across 55 countries with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion. It aims to increase trade by 109% and lift 50 million Africans out of poverty by 2035. However, Africa’s 3,000+ languages pose a major barrier to these goals. Research highlights the economic benefits of a common trade language (Egger & Toubal, 2016; Hutchinson, 2002). Broadly, prior work on the benefits of common trade language draws from various theoretical perspectives, including gravity models (Frankel, 1997), cultural proximity theory (Felbermayr & Toubal, 2010), economic integration theory (Baldwin, 2006), information asymmetry and signaling theory (Spence, 1973) and transaction costs theory (Oh, Selmier, & Lien, 2011)[1]. Unfortunately, none of these theories focus on how a subregional language can be expanded to other subregions to become a common regional or continental language. Kiswahili’s growing use in East and Southern Africa, alongside its adoption by the African Union, East African Community (EAC), and Southern African Development Community (SADC), demonstrates the need for a shared language in intra-African trade. However, no formal strategy exists to promote a common language for intra-regional trade across the continent. Drawing on institutional theory that suggests that the organizational behavior is heavily shaped by the rules, norms, beliefs and practices of its environment, this article proposes a framework based on regulative, normative, and cognitive pillars to promote Kiswahili as the common language for intra-African trade. These three pillars provide a structured approach to establishing a common language by ensuring policy enforcement and standardization (regulative), fostering norms and values (normative), and shaping collective understanding and practices (cognitive), all of which are crucial for Kiswahili’s adoption as a pan-African trade language. We also outline a 25-year roadmap to guide policymakers in implementing this vision.

Navigating Africa’s Linguistic Diversity: The Importance and Challenges of Adopting Kiswahili for Intra-African Trade

Africa has the world’s most linguistically diverse landscape, with over 3,000 languages (Boston University, 2025). Nigeria, DRC, and Ethiopia have over 525, 242, and 109 languages, respectively, while Ghana and Benin together have more than 130 languages (Business Insider Africa, 2024). This diversity, amplified by colonial languages such as English, French, and Portuguese (Kanana, 2013), poses a challenge to AfCFTA’s intra-African trade by hindering communication among traders, businesses, and policymakers (Fanjanirina, 2023). A common language is crucial for overcoming these barriers, as seen in other regional economic integrations (e.g., EU, Mercosur, USMCA).

Kiswahili is a strong candidate for a pan-African trade language. Rooted in Bantu with Arabic influences, it is spoken by over 200 million people in East, Central, and Southern Africa (UNESCO, 2024). As an official language of the East African Community (EAC) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), Kiswahili has become the language of more than 400 million consumers. With 35-40% of its vocabulary derived from Arabic, it is accessible to Northern Africa’s 250 million Arabic speakers. Recognized as a trade language in 14 countries and a working language of the African Union, it extends its reach to 1.5 billion people. UNESCO’s World Kiswahili Language Day highlights its growing significance, alongside its expansion in African educational institutions. While Arabic is a potential contender, its use is largely confined to Northern Africa and lacks Kiswahili’s economic and pan-African influence.

The transition to Kiswahili as a common language for intra-African trade is not without challenges. Africa’s linguistic diversity is deeply tied to cultural identity, and some nations may see Kiswahili’s adoption as an imposition (Mwangi, Nandi, & Okhuosi, 2023). Moreover, political resistance could arise due to the financial costs of education, infrastructure, and policy implementation it requires (UNESCO, 2024). Businesses may also resist, given the time required for mastery, and non-African firms might face difficulties. Unlike Rwanda’s shift to English, which aligned with global trade, prioritizing Kiswahili may pose challenges in engaging global partners. Overcoming these challenges requires investment in education, infrastructure, and policies, alongside a shift of mindset (Chrysostome, Munthali, & Ado, 2019) and crafting a superordinate, culture-transcending identity through strategic educational and cultural initiatives that promote multilingualism and position Kiswahili as a common rather than a replacement language.

Despite these challenges, the transition to Kiswahili as a pan-African language for trade offers significant benefits. It enhances economic integration by reducing language barriers, harmonizing trade policies, and fostering trust in trade (Cuypers, Ertug, & Hennart, 2015; Dow, Cuypers, & Ertug, 2016). More broadly, Kiswahili promotes a shared African identity, free from colonial influence, and mitigates social and economic disparities related to colonial languages (Meija-Martinez, 2017). Its success in unifying diverse groups in East Africa (Habwe, 2009) suggests that its broader adoption could mitigate some challenges associated with colonial languages. However, Kiswahili’s dominance may also deepen regional differences.

In the section below, we draw on institutional theory—regulative, normative, and cognitive pillars—to explain how the transition to Kiswahili as a pan-African language for intra-African trade can be effectively framed and implemented.

Towards an Institutional Theory-Based Model of Establishing Kiswahili as Pan-African Language for Intra-African Trade

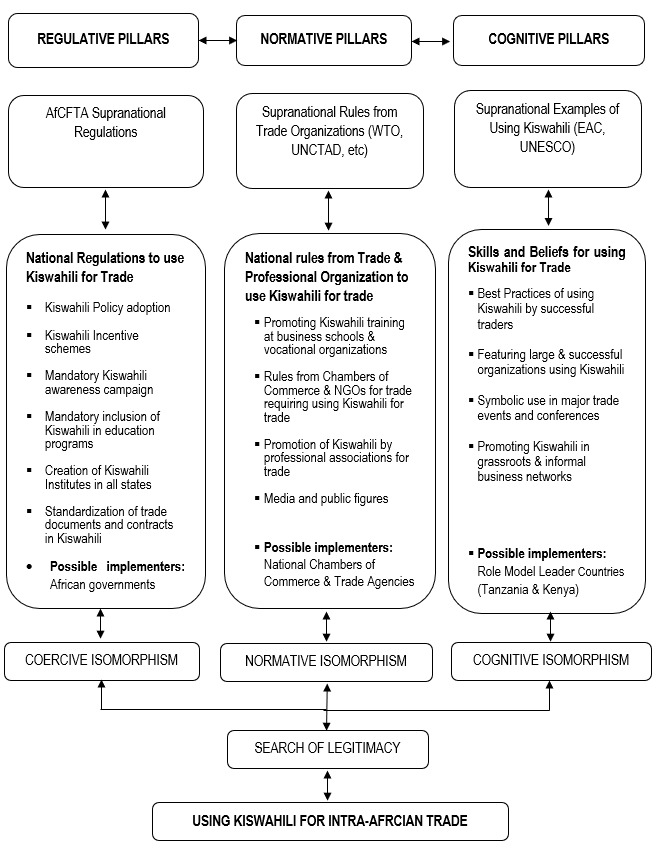

Institutions are the “rules of the game in a society” (North, 1990: 3). Institutional theory identifies three key pillars—regulative, normative, and cognitive—that shape social behavior through rules, norms, and routines (Scott, 1995). We argue that institutions play a crucial role in establishing a common language for intra-regional trade. Specifically, the three pillars influence African traders to adopt Kiswahili for intra-African transactions by conferring legitimacy through compliance with institutional norms. Regulative, normative, and cognitive pressures create coercive, normative, and mimetic isomorphism, driving traders toward Kiswahili. Below, we outline mechanisms for promoting Kiswahili as a pan-African trade language based on these institutional pillars.

Regulative Pillars: Coercive Isomorphism for Using Kiswahili as Common Language

The regulative institutional pillar enforces behavior through regulations, monitoring, and sanctions (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Li, 2010), shaping actions via rewards and penalties (Scott, 1995). This pillar is key to promoting Kiswahili as a pan-African trade language through three mechanisms: harmonized trade policies, education initiatives, and financial incentives.

First, AfCFTA can institutionalize Kiswahili in intra-African trade through regulatory enforcement at national levels. Thus, like the African Union (AU), other pan-Africa institutions, namely African Development Bank (ADB), and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), can recognize Kiswahili alongside English, French, Portuguese, and Arabic as an official trade language. National governments and other institutions like AU mandating its use in customs forms, product descriptions, certifications, and legal documents would ensure uniformity, reduce linguistic barriers, and enhance trade efficiency. Formalizing Kiswahili in negotiations would improve accessibility and transparency for businesses, particularly those less proficient in colonial languages.

Second, education and training can expand Kiswahili’s role in intra-African trade. AfCFTA could establish Kiswahili Institutes in all African countries, modeled after the Goethe Institute, Alliance Francaise, the British Council and Confucius Institute, to provide language training tailored to trade professionals, fostering economic integration. Universities and vocational institutions, with support from African National Education Commissions, could integrate Kiswahili for business and trade into curricula and through specialized programs, making it an integral part of higher education.

Third, the establishment of incentives can encourage Kiswahili adoption for intra-African trade. Governments can offer financial incentives for businesses that use Kiswahili in trade operations. Also, AfCFTA, African Union and other supranational African regional economic blocs and supranational organizations could offer tax breaks, reduced tariffs, subsidies, and preferential loans to businesses using Kiswahili for trade. Such incentives could be particularly beneficial to SMEs to expand their reach in the broader African markets. Additionally, government bodies could provide funding for certified Kiswahili translation and interpretation services within trade institutions along with digital translation tools like DeepL, which would further support linguistic accessibility in intra-African trade.

Normative Pillars: Normative Isomorphism for Using Kiswahili as a Common Language

The normative institutional pillar focuses on cultural norms, values, and expectations that shape behavior in social and commercial contexts (Bruton et al., 2010). These norms guide actions by defining what is considered appropriate. Normative institutions influence behavior through a social obligation to comply. Table 1 presents notable examples of normative pillar that support Kiswahili for cross-border trade. This pillar is key to promoting Kiswahili as a pan-African trade language through two mechanisms: exemplar nations as role models, and endorsement by trade professional associations and business networks.

Specifically, the first mechanism is the role model influence of countries where Kiswahili is well-established, such as Tanzania and Kenya. These nations serve as good examples and can demonstrate how Kiswahili facilitates trade, enhances communication, and strengthens regional cohesion (Xinhua, 2023). By acting as role models, they can inspire other African nations to adopt Kiswahili for trade.

The second mechanism is via different African trade professional associations and business networks, such as the Africa Business Council (AFBC), African Chambers of Commerce, and East African Business Council. These organizations can promote Kiswahili as a standard language for trade by incorporating it into professional codes of conduct. For example, trade unions can include Kiswahili in negotiation protocols, while business associations can encourage its use in industry-specific communication at events like trade fairs and conferences. Additionally, organizations can use Kiswahili in internal communications, meetings, marketing, and customer relations to reinforce African unity and cultural values.

Cognitive Pillars: Mimetic Isomorphism for Using Kiswahili as a Common Language

The cognitive pillar refers to shared beliefs, mental models, and knowledge systems that shape how individuals and organizations understand and engage with the world (Scott, 2007). It emphasizes how cultural contexts shape individual interpretations and beliefs (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 1995). Applying this to Kiswahili’s promotion as a language for intra-African trade shows how its successful use can inspire its adoption by fostering positive perceptions and shared mental models among African traders and businesses. This pillar is key to promoting Kiswahili as a pan-African trade language through three mechanisms: promoting success stories, symbolic use of Kiswahili in pan-African trade events, and integrating Kiswahili into specific industries.

Regarding the first mechanism which is promoting success stories of businesses using Kiswahili, highlighting East African countries like Tanzania, Rwanda, and Uganda, where Kiswahili supports trade, can inspire other regions. These stories, shared through media and business networks, reduce linguistic barriers, build trust, and encourage Kiswahili integration in branding, advertising, and customer service. Featuring banks, shipping companies, and trade enterprises using Kiswahili in advertisements also serves as a powerful signal, demonstrating the practical benefits of adoption.

As for the second mechanism that is the symbolic use of Kiswahili in major pan-African trade events, trade fairs like the Intra-African Trade Fair (IATF) can help institutionalize Kiswahili by incorporating it into signage, promotional materials, and event proceedings, showcasing its role in facilitating trade. Additionally, Kiswahili’s use in grassroots movements and informal networks, such as East African women traders, can further strengthen its symbolic significance across the continent, thereby inspiring counterparts across Africa.

Finally, about the third mechanism, namely the integration of Kiswahili into specific industries, the telecommunications industry in East Africa is a great example. Safaricom’s Kiswahili slogans, like Twende Tukiuke (“Let’s Go Beyond”), build relatability and loyalty with local customers. Likewise, campaigns like Lipa Mdogo Mdogo (“Pay Little by Little”) and M-Pesa (“Mobile Money”) foster accessibility and trust, reinforcing Safaricom’s market leadership. Similarly, Vodacom’s Cheka kwa Vodacom (“Laugh with Vodacom”) and Equity Bank’s Pamoja na Wewe (“Together with You”) strengthen cognitive associations between Kiswahili and empowerment, embedding it into the socio-economic fabric as a unifying trade language.

To sum, Kiswahili can be institutionalized as a unified language for intra-African trade through the use of regulative mechanisms (harmonized trade policies, education initiatives, financial incentives), normative mechanisms (regional leadership, African trade associations, business networks), and cognitive mechanisms (success stories, symbolic uses, industry examples). Given Africa’s dynamic institutional environment, we acknowledge that regulatory and normative changes could impact the adoption process. To address this, we propose a flexible and adaptive governance framework that includes policy reviews, stakeholder consultations, and monitoring to assess the language’s effectiveness in trade facilitation. This approach ensures adaptability to political, economic, and social changes over the next 25 years. Figure 1 illustrates the Pan-African Language Development model for Intra-Africa Trade, and Table 2 presents a 25-year phased implementation roadmap for Kiswahili in intra-African trade. A 25-year time frame was chosen to allow for a gradual, phased implementation of Kiswahili as a common Pan-African trade language, aligning with the long-term goals of initiatives like the African Union’s Agenda 2063, and providing enough time for policy development, education, and infrastructure adjustments, and regional cooperation while adapting to the evolving linguistic and political landscape.

Conclusion

This paper draws from institutional theory to propose a framework for promoting Kiswahili as the common language for intra-African trade. It suggests that AfCFTA policymakers and African governments should prioritize Kiswahili as the language for intra-African trade by adopting the regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive initiatives outlined in this paper (See Table 2). Promoting Kiswahili will reduce trade costs and boost economic integration, but will require substantial investment in language education, translation infrastructure, and policy harmonization. The proposed framework offers a theoretical foundation for scholars exploring the socio-economic and cultural impact of a common trade language in Africa. However, its reliance on Scott’s (1995) institutional theory overlooks linguistic theories and African languages and cultural specificities. Future research could address these gaps by investigating the linguistic dimensions of promoting Kiswahili, testing the framework in sub-regional contexts (e.g., East, Southern, Northern Africa), and examining how regional economic integrations affect language adoption. Additionally, research could explore how historical political ties with former European colonizers influence Kiswahili’s promotion for intra-African trade. Given Africa’s evolving institutional landscape, we recommend periodic reviews of the proposed policy initiatives to ensure adaptability to political, economic, and social changes over the next 25 years. Some potential challenges may arise during periodic reviews such as resistance to change from stakeholders, inconsistencies in implementation across regions, and unforeseen political and socio-cultural factors that may affect the policy’s effectiveness. To address these challenges, we propose strategies such as engaging key stakeholders in continuous dialogue, establishing a robust monitoring and evaluation framework, and ensuring flexibility in policy adjustments. These actions will help mitigate potential risks and contribute to the successful implementation of Kiswahili’s adoption as a pan-African trade language.

About the Authors

Elie V. Chrysostome is Professor of International Business at Ivey Business School of Western University in Canada and Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Comparative International Management (JCIM). He previously taught at Laval University (Canada), University of Moncton (Canada) and at The State University for New York (USA). He is author and coauthor of more than 50 publications in various journals including Journal of International Business Policy, Thunderbird International Business Review, Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Journal of African Business. His research interests include Immigrant & Transnational Diaspora Entrepreneurship, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in Emerging Markets, impact of sanctions on MNEs in Africa & Capacity Building in Africa.

Abiodun Adegbile is an Associate Professor of Management at Birmingham City University Business School and a Senior Fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy. He has a PhD in Business Administration and Economics from the European University Viadrina, Germany. His research focuses on entrepreneurship, international business, strategy, Migration and integration in Africa and other emerging markets. His work has been published in Journal of Small Business Management, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Journal of Business Research, IEEE Transaction in Engineering Management, and International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research.

Christopher Boafo is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Management and previously served as a Research Fellow at Leipzig University’s SEPT Competence Center. His research focuses on Indigenous people, international entrepreneurship, the internationalization of informal small businesses, and international knowledge transfer through university-business collaborations in emerging markets. He holds a PhD in Management Science (focusing on Business Administration) with Summa Cum Laude from Leipzig University in Germany. His work has been published in the Africa Journal of Management, International Small Business Journal, Thunderbird International Business Review, and International Journal of Management Education.

Fuhad Ogunsanya is pursuing a PhD in International Business at Ivey Business School of Western University in Canada. His research interests include Foreign Direct Investments in African countries, Internationalization Strategies of Emerging Countries MNEs (EMNEs), Passive Investments, and Outliers in International Business. He holds a MSc with distinction in International Business from Warwick Business School, University of Warwick in UK.

Gravity models suggest that using a common language for trade increases bilateral trade (by more than 30% according to some economists) because it helps to reduce communication costs by allowing a direct communication and making trade easier (Frankel, 1997). The cultural proximity perspective suggests that common language contributes to reduce cultural differences and that this contributes to reduce miscommunication and lack of trust and as such helps to trade more easily (Felbermayr & Toubal, 2010). The economic integration perspective advocates that using a common language facilitates trade policies harmonization between countries that are trading and that this helps to increase the volume of trade between these countries (Baldwin, 2006). As for the information asymmetry and signalling theory (Spence, 1973), these theories suggest that using a common language reduces the information asymmetry between traders and helps to build trust which reduces transactions costs and to increase the volume of trade. These different perspectives are consistent with the transaction costs perspective that suggests that a common language reduces transactions costs of trade and increases the volume of trade (Oh, Selmier, & Lien, 2011).