Introduction

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is a groundbreaking initiative with the potential to significantly enhance trade and investment across Africa by enabling the free movement of goods, services, and capital. It also has the capacity to transform global trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) patterns. As of August 2024, the AfCFTA agreement has been signed by 54 member states, with 48 having ratified it (AfCFTA, 2024). This makes it the largest free trade area by member states, since the introduction of the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Debrah, Olabode, Olan, & Nyuur, 2024).

Nonetheless, AfCFTA faces significant challenges, perhaps not least of which is how an agreement with so many members can work in practice. Another potential issue is that Africa does not have a long history of standing united, due to its colonial history; in fact, many African countries have a short history of being nation-states (Heldring & Robinson, 2012). Furthermore, Africa presents a wide range of political systems, varying from relatively free and fair democracies to highly repressive regimes, alongside economies that span from developing to middle-income levels, as well as a rich tapestry of languages and cultures. This diversity, along with the varying motivations of member countries, complicates the effective implementation of AfCFTA.

The question, therefore, of whether and how AfCFTA can be leveraged to support international business (IB) within Africa is both reasonable and critically important, not only for academic discourse but also for practitioners. In this paper, we offer guidance informed by earlier attempts at regional integration through the African Regional Economic Communities (RECs) (Getachew, Fon, & Chrysostome, 2023), which have yielded mixed results, as well as lessons from the successes and setbacks of European integration. For managers of African firms, we provide strategies they can use to improve decision-making on trade and FDI, particularly to leverage economies of scale, use regional value chains, and consider different entry modes. For African policymakers at a supranational level (e.g., the AfCFTA Secretariat), we provide suggestions on how to enhance economic growth and address challenges in sustainability, poverty, and inequality, specifically to 1) focus on deepening integration, 2) create cross-country platforms, 3) attend to infrastructural development, and 4) address unequal distribution of benefits. For policymakers at a national level, we suggest strengthening national institutions, leveraging supranational initiatives, and addressing the uneven distribution of benefits.

African Regional Economic Communities

The African Union (AU) defines Regional Economic Communities (RECs) as “regional groupings of African states […] the purpose of the RECs is to facilitate regional economic integration between members of the individual regions and through the wider African Economic Community”.[1]

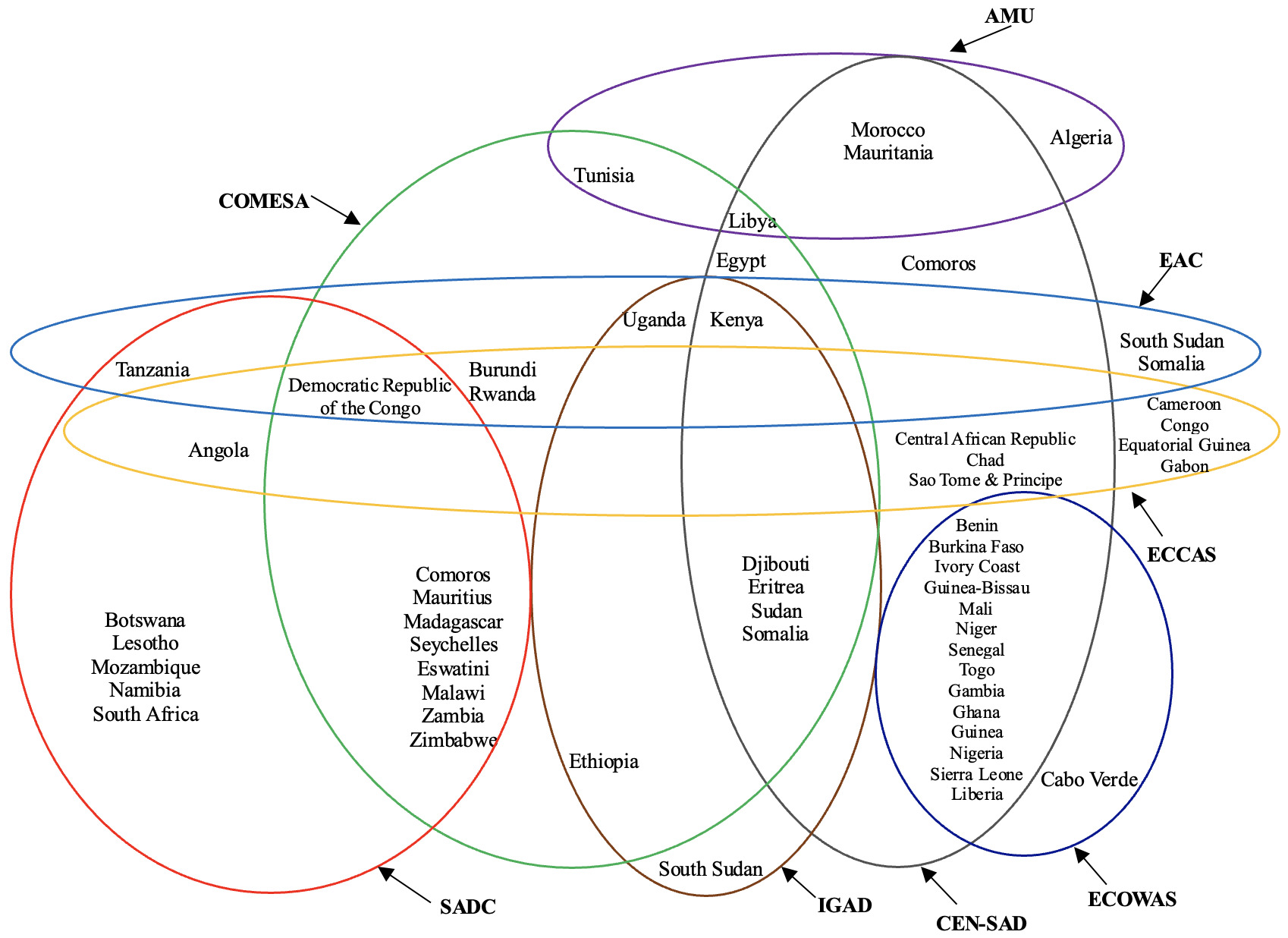

Today, the AU recognizes eight RECs, namely the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Most countries belong to two or more RECs, creating a “Spaghetti Bowl” effect (figure 1). This creates complexity in trade relations among African countries and is one of the impediments to the integration efforts of African RECs.

While some RECs have made progress towards integration, others have stalled. Table 1 shows REC scores across key dimensions of regional integration using the Africa Regional Integration Index (ARII). The indicators are chosen to reflect integration efforts and are aggregated into five dimensions. [2] Each dimension ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the highest level of integration.

Overall, integration levels of the RECs in Africa are low. SADC and CEN-SAD registered the lowest overall scores, followed by COMESA. The lowest scores for the dimensions were observed in infrastructural integration (the extent to which a country has adequate infrastructure) and productive integration (a country’s involvement in the regional supply and value chain), which are crucial for international business and regional value chain activities. These low integration levels across various dimensions have limited the success of the RECs in driving trade and investment across the African continent. In contrast, RECs with higher levels of integration (such as EAC) experienced stronger investment flows (Getachew et al., 2023).

One of the factors for the relatively better performance of the EAC is its significant success in the elimination of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) affecting its trade flows. In 2015, the EAC passed the East African Community Elimination of NTBs Act, which provided a legal framework for resolving reported NTBs. This act resulted in the highest share of resolved NTBs, with customs and trade facilitation measures being the most frequently resolved (ODI, 2017).

Several factors account for the overall low integration levels. First, the RECs differ in the number and depth of provisions[3] (see Table 2). The number and depth of these provisions reflect the strength of the supranational institutions within the RECs, with fewer and less substantive provisions indicating weaker supranational institutions (Getachew et al., 2023). Second, weak national institutions have led to member states’ poor implementation of REC provisions. Table 2 also shows the average rule of law index of all member countries for a sample of RECs. It ranges between -2.5 and 2.5, where -2.5 reflects the worst rule of law environment and 2.5 the best. Third, most African countries have low participation in global value chains, particularly through backward linkages, because they rely more on exports of raw materials outside Africa (Amendolagine, Presbitero, Rabellotti, & Sanfilippo, 2019). Fourth, the lack of adequate physical infrastructure has hampered the flow of goods.

The levels of integration largely depend on the willingness of member states to share their sovereignty with REC institutions. However, across several RECs, the reluctance of member states to cede some authority and adopt common standards and regulations has weakened the potential for deeper integration (UNCTAD, 2013). Weaker supranational institutions on services across several of the RECs are particularly concerning, given that nearly half of intra-African cross-border investments are in services, especially financial services (Ibeh & Makhmadshoev, 2018).

The European Experience

While we recognize the differences between European integration and AfCFTA, we believe that drawing lessons from the European experience can help us understand both the upsides and challenges of integrating a large number of member states. What Africa and Europe have in common is the large number of countries and diversity within. And since European integration started earlier and has advanced further than in other regions, it offers lessons that may not exist elsewhere. European integration started as an effort to bring peace and prosperity to the continent post-World War II. Although some roots go back to the 1944 Benelux Union, the Treaty of Rome in 1958 set off the initiative. Significant steps forward include the common agricultural policy, various enlargement steps, the introduction of the Euro, and the single European market (Lelieveldt & Princen, 2023).

When looking into the more recent European experience, we observe several lessons, starting from what has worked and then moving on to its failures. The single European market project and enlargement proved highly successful because it was underpinned by political stability, offered economies of scale to MNEs, and the European Union (EU) took on the role of creating and managing markets. This has not only led to a quantitative growth in FDI but also allowed for a ‘qualitative’ shift towards higher-risk entry modes – substituting trade with investments, especially through wholly-owned subsidiaries (Blevins, Moschieri, Pinkham, & Ragozzino, 2016). Merger and acquisition activity has moved from being primarily domestic to now being dominated by cross-border investments (Blevins et al., 2016). Moreover, the industrial and labor landscapes have become more homogeneous over time through both European-wide legislation and cross-country learning.

Whenever the European integration project has stuttered, it was either due to insufficient decision-making structures to move it forward or political disagreements between and within member countries. For instance, it took decades to achieve a single market, which had been the objective from the outset, because of the lack of supranational decision-making and implementation. More recently, Brexit has proven that public support for European integration is hard to maintain. Presently, differences over issues like immigration, the impact of trade and investment on inequality, and the attitude towards Russia and China are negatively affecting European integration (Lelieveldt & Princen, 2023).

Another problem has been the multi-speed nature of integration and associated benefits. To this date, there is the EU itself and the wider European Economic Area. There is also a perception that core countries have benefited from integration more than peripheral ones. To an extent, FDI has helped to overcome these issues. In the car industry, for instance, there has been a shift from countries like Germany and France towards Central and Eastern Europe, through component manufacturing and eventually assembly. We discuss the implications of these observations further below.

Lessons for Policymakers and Managers

AfCFTA represents a major step forward for African economic and trade integration. However, there are challenges, especially due to the large number of countries involved, each with distinct economic, political, and social characteristics. What lessons can we learn from the integration efforts of RECs and the EU?

The first key lesson is that weak supranational institutions can hinder the benefits of regional integration, particularly in enhancing trade and investment flows. This is evident as intra-African FDI flows have increasingly gravitated towards RECs with stronger supranational institutions. However, it is concerning that many RECs still lack strong supranational institutions for services, although a substantial portion of cross-border investments is concentrated in this sector. When the EU’s supranational institutions eventually became stronger, this promoted trade and FDI but also enabled firms to shift parts of their value chains to other countries and adopt higher-risk entry modes. Second, institutional variation among member states may hinder the adoption of supranational initiatives and policies. Such variation adversely affects multinational firms as it increases their cost of business, compliance, and adaptation. However, the European experience demonstrates that economic integration can gradually make institutions and markets more similar. Finally, the experiences of European and African integration efforts indicate that the distribution of returns can be uneven across member states. This disparity in the distribution of returns can undermine political support for integration efforts. Additionally, political disagreements between and within member countries can further compromise their effectiveness. Table 3 below summarizes these lessons and their implications for international business in Africa.

So, what can be done to address these issues and promote international business? Policymakers at the supranational level, such as the AfCFTA Secretariat, ought to focus on deepening integration to generate scale benefits that enhance trade and investment, making the intra-African market more appealing for investment. To this end, the AfCFTA Secretariat could prioritize efforts to align institutions and create a more integrated market. However, these changes should be implemented gradually. The AfCFTA Secretariat should focus on creating platforms for knowledge-sharing, capacity-building, and gradual alignment of policies among member states to encourage convergence without demanding immediate uniformity. Greater attention needs to be given to infrastructural development and the creation of substantive protocols to support service investments. Furthermore, addressing the unequal distribution of benefits is important to sustain political support. The Secretariat can support measures that build the capacity of countries with weaker institutions to attract investment. This could involve technical assistance, targeted funding mechanisms, and the development of support programs that help less-developed members improve their investment climates. Finally, facilitating dialogue to overcome political disagreements is essential.

At the national level, policymakers should focus on strengthening national institutions to maximize the benefits of integration. Since countries with stronger institutions tend to benefit more from inward investment, governments should prioritize strengthening legal, regulatory, and financial institutions to become more competitive. This involves reforms in areas such as contract enforcement, property rights, and transparency, which can enhance market attractiveness to investors. Additionally, governments can leverage supranational initiatives to improve competitiveness. By using the frameworks and support mechanisms offered by AfCFTA and RECs, they can implement domestic reforms that align with regional standards, helping to integrate their economies more deeply into regional value chains. Managing domestic political consensus is also crucial. National policymakers must address concerns about the uneven distribution of integration benefits to maintain public support. Policies that ensure equitable economic gains, such as social safety nets, investment in education, and targeted regional development programs, may help mitigate political backlash.

For managers of African firms, deeper integration offers significant opportunities. The REC scores in Tables 1 and 2 can be useful for identifying locations with deeper integration and stronger supranational institutions, such as the EAC, to establish foreign subsidiaries. For example, a firm looking to invest in the service sector would find it beneficial to do so in the EAC region, where service provisions are substantive. Managers should look for opportunities to leverage the expanded market created by AfCFTA to enhance competitiveness, which might involve expanding production capacity or adapting product offerings to meet the diverse needs of markets. Additionally, firms can strategically utilize regional value chains by shifting parts of their value chains across borders, as seen in Europe. For example, Volkswagen has strategically structured its production networks across various European nations to benefit from the EU’s unified market (Pavlínek, 2025). Managers should explore opportunities to localize parts of their (service) production processes to optimize costs, benefit from local expertise, or respond to market demands. In doing so, they need to consider different entry modes, such as joint ventures or wholly owned subsidiaries, to manage risks in diverse institutional environments.

Moreover, firms should adapt their strategies to institutional variations. Given that large institutional differences remain across African countries, firms should conduct thorough due diligence and adjust their market entry strategies to the unique institutional environment of each country.

Finally, the introduction of AfCFTA presents significant business opportunities in infrastructure. According to the African Development Bank (2024), Africa requires between $130 billion and $170 billion annually to close its infrastructure gap. Multinational firms, particularly in sectors such as transportation, energy, and information technology, should leverage these opportunities.[4] By doing so, they will also contribute to the success of AfCFTA. Table 4 below summarizes these actionable insights and directions.

Conclusions

We zoomed in on how AfCFTA can best enhance trade and FDI in Africa. AfCFTA can learn from the intra-African lessons that RECs present and the European integration experience. We suggested a number of specific implications that African policymakers and managers can take on board in their efforts to further AfCFTA and more evenly distribute benefits across the continent.

About the Authors

Roger Fon is an Assistant Professor of International Business at Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, and a visiting lecturer at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research focuses on the internationalization of multinational enterprises from emerging economies, FDI and host-country institutional change, the non-market strategies of multinational enterprises and the institutional and strategic motivations of multinational enterprises’ investments in Africa. His work has been published in the Journal of International Business Policy, International Business Review and Thunderbird International Business Review.

Yamlaksira S. Getachew is an Assistant Professor of Strategy at Babson College. His research focuses on the interplay between businesses and sustainable development, with a particular emphasis on Africa, economic institutions, and inequality. His work has appeared in leading management journals such as Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, Journal of World Business, Global Strategy Journal, and Journal of International Business Policy.

Michael J. Mol is a Professor of Strategic and International Management. His research focuses on the strategic management of larger firms, with a particular interest in issues including management innovation, corporate social (ir)responsibility, offshoring and outsourcing, and strategy in Africa. He has published widely on these topics and has won several awards for his work, including the Academy of Management Review best article award. He serves or has served on the editorial board of over a dozen journals.

AU, “Regional Economic Communities,” African Union, 2024, https://au.int/en/organs/recs

See UNECA for the methodology, https://arii.uneca.org/

Substantive vs shallow provisions distinguish legally enforceable provisions from what is just negotiated (Guillin, Rabaud, & Zaki, 2023).

https://www.afdb.org/en/knowledge/publications/african-economic-outlook