Introduction

Scientific evidence has shown that growing human activity has put the world’s natural and social ecosystems under intense pressure (Hjalsted et al., 2021). Moreover, despite efforts by the United Nations to introduce standards for minimizing the impact of industrial activity, progress has been halting. Furthermore, notwithstanding the funds allocated to sustainable initiatives by firms, traditional ‘sustainability-as-usual’ practices (conventional efforts to reduce harm in the short term instead of systemic changes for the long run) will be insufficient to face the upcoming global challenges (Godelnik, 2021). Thus, businesses need to take a leap into comprehensive sustainability, developing new sustainability competencies and multi-stakeholder-oriented initiatives (Vargas et al., 2022), as well as creating value at multiple stakeholder levels (Konietzko, Das, & Bocken, 2023), while government policymakers need to develop new assessment methods for measuring the sustainability progress of companies.

While multinational companies (MNCs) face pressure to adapt to the environments in which they operate, they also face pressures to standardize their processes, and this standardization could lead them to conduct their operations without caring about their effects on others (Teehankee, 2005). Conversely, species in nature form symbiotic relationships, using their unique characteristics and advantages (Cordova & Schmitz, 2023) and becoming neutrally or even positively integrated with other components of their ecosystem, while simultaneously developing their role as part of nature.

According to Teehankee (2005), in contrast to companies driven by economic interests only and unaware of their externalities, so-called ‘living companies’ usually measure (business) success through their capacity for adaptive learning, which is a valuable skill that helps businesses to adapt to evolving and complex contexts, such as those associated with sustainability, across global operating environments. In addition, by developing systems thinking competency, leaders adopt a bird’s-eye view, identifying the single elements and their interactions within those complex systems, which helps them obtain a broader understanding of a global societal picture (Von Bertalanffy, 1972), and enabling them to prevent unsustainable practices. While important in a domestic sense, this is particularly beneficial in relation to international systems, including operations in different countries.

Although using the systems perspective is helpful on a theoretical level, large-scale practical adoption in the economic system is mostly missing (Wahl, 2016). Moving from traditional ‘sustainability-as-usual’ practices to a comprehensive sustainability perspective means transitioning responsibly from doing less harm to the environment to actively and positively participating in it, using the way nature operates collaboratively as a benchmark (Wahl, 2016).

Hence, with the lack of notable progress in making businesses more sustainable, new integrative approaches are needed to improve the understanding of businesses’ environmental impact (Gunderson & Holling, 2002). Our central research question is: How can MNCs be more accurately assessed and guided toward sustainability using a nature-based framework rooted in systems thinking and sustainability competencies? Therefore, inspired by some business theories’ similarities with species’ behavior in natural ecosystems (Cordova & Schmitz, 2023), we propose a nature-based firm classification—living, dead, and zombie firms—and a corresponding competency-based transition framework that addresses how companies can navigate through the stages of incorporating sustainability competencies (Brundiers et al., 2021). This article contributes to sustainability literature by offering a novel, integrated classification and decision-making tool that combines ecological systems logic with business strategy, enhancing the potential for transformative change.

A Nature-Based Systemic Perspective

Given the mainly economic orientation of MNCs, we argue that companies must be accountable for incorporating new adaptive skills and sustainability competencies as well as taking a bird’s eye view that ensures they can look beyond organizational borders, becoming fully responsible for their impact on the entire systems in which they operate. Therefore, we propose classifying firms into three nature-oriented categories according to their comprehensive sustainability behavior: (i) living firms, (ii) dead firms, and (iii) zombie firms.[1]

Living Firms

Living firms are respectfully interconnected with their ecosystems. As with living beings in nature, these firms form positive synergies in their contexts and abroad, as well as mutually beneficial symbiotic relationships, considering their characteristics and advantages. Their operation has mitigated all plausible negative impacts, as they have fully identified their potential effects while providing added value to their stakeholders. This category denotes a firm’s capability to not represent any immoral, unethical, or illegal threat to any part of the global ecosystems, while remaining an active participant.

Dead Firms

Dead firms’ behavior is indifferent to their ecosystems. As they are not in full balance with their contexts, strong efforts (i.e. extended sustainability reports) and a lot of resources (i.e. funding several ‘sustainability-as-usual’ practices) are needed to keep them going. They disregard the negative externalities of their operations to ensure financial performance and economic profitability. These firms obtain results within the law without awareness of the multiple impacts they generate in the system.

Zombie Firms

Zombie firms behave against their ecosystems, only following their own individual interests. They contaminate their environment and other organizations with their harmful practices. These organizations can perform informal, corrupt, unethical, and/or illegal activities. Moreover, their disease is highly contagious, infecting others through partnerships, joint ventures, networks, influence, and/or positions of power.

We argue that living firms could be like any other living being or system. However, dead and zombie firms do not adequately fit in with natural ecosystems, being unaware of their operations’ impacts on their stakeholders. Even more, zombies use socially unacceptable behaviors to keep going. Table 1 exhibits how the three proposed categories are sequentially related.

How Do We Create ‘Living’ Firms?

What advances do companies need to make on a skills and competence-related basis to transition between the different scenarios of zombie, dead, and living firms? Certain competencies are essential to advancing sustainable development (Lozano, Merrill, Sammalisto, Ceulemans, & Lozano, 2017; Rieckmann, 2018). Like Ellis (2018), we advocate rethinking the management studies competence framework[2], and transferring it to the business sector. We use the different sustainability competencies, which Brundiers et al. (2021) identified, to determine development or transition pathways between the various categories, and share suggestions on how to transition between them. The following sustainability-related competencies have been highlighted in higher education and thus hold relevance for future managers: implementation, systems thinking, strategic thinking, values thinking, and futures thinking. Additionally, integrated problem-solving and interpersonal aspects serve as an umbrella for the framework.

Implementation competency refers to the combined capacity to effectively execute a predetermined solution in alignment with a vision informed by sustainability principles. This competency encompasses the ability to closely monitor and evaluate the progress of the implementation process, as well as the capability to address any unforeseen challenges or necessary adjustments that may arise.

Systems thinking competency refers to the capacity to collectively examine intricate systems across various domains, such as society, environment, and economy, and across different scales, from local to global. Systems thinking involves considering the interconnectedness of components, the potential for cascading effects, the presence of inertia, feedback loops, and other systemic characteristics relevant to sustainability concerns.

Strategic thinking competency involves identifying the historical origins and inherent durability of intentional and unintentional unsustainability and the obstacles that impede efforts to bring about change. Additionally, it entails the capacity to devise innovative experiments to test various solutions.

The competency of values thinking entails the ability to discern between intrinsic and extrinsic values. It involves the recognition of normalized oppressive structures, as well as the identification and clarification of one’s values. This competency also explains how values are reinforced within specific contexts, cultures, and historical periods.

The ability to engage in futures thinking, such as visions and scenarios, is an essential competency, also known as anticipatory competence (see Schmitz & Cordova, 2023). This involves actively challenging the prevailing status quo and acknowledging the implicit assumptions about societal functioning, worldviews, and mental models that often go unnoticed.

The capacity to effectively utilize integrated problem-solving competency involves combining and integrating the many elements of the sustainable problem-solving process or competencies. This is achieved using relevant disciplinary, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and other forms of knowledge that could be generated by multicultural and multifaceted international business activity.

The ability to effectively apply the principles and procedures of each competency in a manner that goes beyond basic technical skills is known as interpersonal competency. This involves actively engaging and motivating varied stakeholders, as well as empathetically collaborating with others who possess different ways of knowing and communicating.

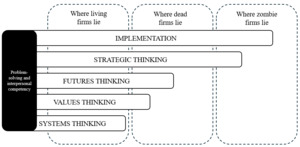

Living firms integrate, use, and reflect all these sustainability competencies. However, dead and zombie firms focus more on strategic rather than values-based competence, competition over collaboration (i.e. interpersonal competence), and basic aspects such as linear, easy-to-fix solutions disregarding systems perspectives (see Figure 1). To help businesses understand their competency deficiencies and the benefits of addressing them in an international business context, we have summarized short- and long-term strategies in Table 2.

Therefore, following the nature-based view that defines our proposed classification of firms, as well as the five core sustainability competencies identified by Brundiers et al. (2021) as necessary to advance sustainable development, it would be possible to identify some real cases of firms in these categories. As depicted in Figure 1, we argue that living firms would simultaneously use the five core competencies to go beyond ‘sustainability-as-usual’ practices (mostly used by dead firms), providing complete transparency regarding their operations. Dead companies would mostly use implementation and strategic-thinking competencies to develop their business operations, as well as future thinking and values thinking in an incipient way to secure their survival and motivate their workers, staying within the law, but mainly going after more profits, and exhibiting low levels of accountability and transparency. Finally, zombie firms would be experts in developing implementation competency to increase their profits, but would use illegal and/or unethical practices without being concerned about accountability to their stakeholders.

Actionable Recommendations for MNCs and Government Policymakers

This paper suggests that firms and policymakers should be mindful of new assessments, regarding comprehensive sustainable development that goes beyond the traditional ‘sustainability-as-usual’ initiatives. On the one hand, companies that pass such assessments could obtain more financial resources from banks and better opportunities to trade with governments. Also, firms would have the opportunity to rethink their international business practices, incorporating a systemic perspective in the decision-making process, value-based thinking in their organizational culture, and strategic foresight in their strategy planning, allowing them to achieve a responsible bird’s-eye view over their local and international impacts.

On the other hand, dead and zombie firms could be prevented from obtaining a social license to operate. Hence, these companies would need to work on fostering the competencies required to move towards a living status if they wanted to thrive. Nevertheless, we also consider that there could be intermediate levels between the three categories proposed, which could help firms to make this transition.

Firms could, first, align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and establish a nature-based view for decision-making. This approach draws inspiration from ecological systems, focusing on balance, interdependence, and adaptability. For example, businesses could integrate these principles into their corporate governance to guide resource allocation and strategic planning. By doing so, firms could mitigate their environmental impact and build resilience against systemic risks, fostering a business model that would thrive within planetary boundaries. Second, systems thinking enables practitioners to view their businesses as interconnected with larger ecosystems, supply chains, and social systems. By understanding these interdependencies, firms could identify their operations’ cascading effects and uncover hidden innovation opportunities. Training programs, simulations, and cross-departmental workshops could equip teams with this competence. This holistic approach would ensure that business decisions accounted for long-term sustainability, reducing unintended consequences and enhancing operational efficiency.

Third, the dynamic challenges of sustainability require businesses to cultivate adaptability among their workforces. Adaptive competency programs could include training on foresight, scenario planning, and strategic problem-solving. Tailored to industry-specific needs, these programs would prepare employees to anticipate and navigate uncertainties while leveraging emerging opportunities. By embedding these competencies into professional development, firms could ensure their teams were equipped to innovate and drive sustainable growth in evolving contexts.

Lastly, living laboratories can provide a real-world testing ground for sustainable practices and innovations. These pilot projects apply principles such as regenerative design and circular economy models in controlled environments. Collaborations with academic institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and government agencies can support these initiatives, enabling firms to experiment with novel approaches. Successful results from these labs can serve as scalable solutions, demonstrating the feasibility of transformative practices while minimizing implementation risks.

Regarding government policymakers, they would have to incorporate incentives and mechanisms to promote the generation of or leap towards ‘living’ firms. New assessment methods going beyond voluntary sustainability (e.g., United Nations Global Compact or Global Reporting Initiative) or even mandatory reporting would be needed to identify these categories, since the existing evaluation systems and certification schemes, such as B-Corp Business[3], or the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas[4], do not include a firm’s achievement of a nature-based structure by advancing the main competencies firms need to transition into genuinely sustainable models. In addition, policymakers would need to be aware of the competencies they would need to assess and promote to generate more living firms.

Conclusion

Classifying firms under the three nature-based categories of living, dead, and zombie will enhance our understanding of how comprehensively companies deal with their environmental and social impacts. In addition, as these categories will label firms according to systems thinking, in terms of being aware of their multiple-level impacts as well as their direct and indirect effects in different locations of the value chain, firms might (re)evaluate the international business activities they conduct that affect their stakeholders.

Second, while dead firms limit their behavior by engaging only in ‘sustainability-as-usual’ practices, zombie firms endanger the business environment, infecting other companies with illegal, unethical, and corrupt operations. In this sense, both put the achievement of overall comprehensive sustainability under severe risk. Thus, we need these companies to be willing to move upstream towards being alive.

Finally, for companies with transactions and stakeholders abroad, the systems thinking perspective could be further stressed and reinforced by this nature-based view of firms, through asking MNCs to be aware of their effects on multiple stakeholders and to operate proactively to organically merge with their environments, leaving no indirect or unnoticed collateral damage behind.

About the Authors

Miguel Cordova is Associate Professor at the Department of Management and Leadership, Business School, at Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico. He holds a PhD in Strategic Management and Sustainability. His research is oriented to Power and Influence in Organizations, Sustainability, Strategic Management, Global Supply Chains, Blue Economy, and International Business.

Marina A. Schmitz serves as a Researcher and Project Manager, and external Lecturer at IEDC-Bled School of Management in Bled, Slovenia as well as CSR Expert/Senior Consultant at Polymundo AG in Heilbronn, Germany. Passionate about reforming the economy and management education for a sustainable society, she engages in international research on innovative pedagogy and implementation of sustainability. Her background includes sustainability consulting and business transformation, highlighting her commitment to inclusivity and sustainable business practices.

Tjaša Cankar is a doctoral candidate at the Institute for Cultural and Memory Studies at the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. She researches the production of gender knowledge in the semi-periphery with a focus on epistemic (dis)continuities during the Yugoslav transition. She is also a researcher at the IEDC–Bled School of Management, working on equal opportunities in management. She has been involved in several EU projects (Horizon Europe, Erasmus+) on institutional capacity building and gender equality policy development.

Livija Marko holds a degree in International Relations from the University of Ljubljana and a Master’s degree in International Law from the University of Edinburgh where she specialised in international human rights law, international environmental law and climate change law. She has extensive experience managing research projects, educational programmes and academic conferences across government, the private education sector and at the Institute for Ethnic Studies, one of the oldest research institutes in Europe studying minority rights, ethnicity and diversity management.

We acknowledge that the terms “zombie,” “dead,” and “living” firms have established meanings in other disciplines. In finance, “zombie firms” refers to companies that survive through prolonged credit despite being unable to cover debt costs (see Caballero, R. J., Hoshi, T., & Kashyap, A. K. (2008). Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1943–1977). In business demography, “dead firms” typically denotes organizations that have exited the market due to failure or closure (see McGowan, M. A., Andrews, D., & Millot, V. (2017). The Walking Dead? Zombie Firms and Productivity Performance in OECD Countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1372). The concept of a “living company,” as introduced by de Geus (1997) (see de Geus, A. (1997). The Living Company. Harvard Business Review Press), describes adaptive, learning-oriented organizations focused on long-term survival. Our framework reinterprets these terms metaphorically through a nature-based, sustainability-oriented lens.

The management studies competence framework outlines the essential skills and knowledge needed for effective management. This framework helps guide the development and assessment of managers in their professional growth.

The B-Corp evaluation system uses the B Impact Assessment to measure a company’s social and environmental performance in five areas: governance, workers, community, environment, and customers.

The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas is an evaluation tool that expands the traditional business model by adding environmental and social layers to the economic one.