Introduction

International business (IB) scholars have long noted the vast complexity faced by multinational corporations (MNCs) due to the heterogeneity of their key units of analysis – the nation and the firm –, the complexity of the networks connecting these units, and the rapid evolution of the global business system, making them among the most complex organizations. At the same time, over the past three decades, we have witnessed the rise of complexity theory as an interdisciplinary field focused on the science of evolution, changing organizational forms and structures, and the emergence of new capabilities. We show how establishing connections between complexity theory and IB provides useful insights for managers and practitioners.

This paper examines the evolving dynamics of MNCs as complex adaptive systems and offers practical guidance for managers by introducing key concepts from complexity theory, including emergence, modularity, and nearly decomposable systems. By focusing on the mechanisms that drive organizational evolution – and not just short-term coordination – this paper provides insights to help managers design strategies that enable MNCs to adapt and grow in ever-changing and complex global environments.

Self-Organization Between Order and Disorder

Dominant MNC frameworks, such as the integration-responsiveness grid (Prahalad & Doz, 1987) and the differentiated network (Nohria & Ghoshal, 1997), posit the fundamental tension between global integration and local differentiation as the challenge that MNCs have to navigate through proper organization design. In contrast, complexity theory as applied to business organizations posits a different fundamental tension facing organizations. One can call this the tension between order and disorder. Depending on the context, this spectrum may range from highly structured to loosely structured systems, from rugged to smooth landscapes, or even from order to chaos. The underlying principle, however, remains the same: the extent to which conditions favor or hinder self-organization. These conditions shape how organizations dynamically adapt, allowing new structures to emerge spontaneously – ones that could not have been planned or predicted through prior analysis.

The tension between order and disorder is especially relevant to high-velocity markets where there is simply too much uncertainty to rely on top-down organization design and firms need to adapt on the “edge of chaos” (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1998). VISA, under the leadership of Dee Hock, fostered what Hock called a “chaordic” organization, explicitly balancing chaos and order (= chaordic) to foster decentralized evolution. Hock dispensed with efforts to mastermind an overall structure, instead launching VISA as a decentralized arrangement that allowed regional units to develop autonomously while sharing a certain set of protocols (Hock, 1999).

Self-organization between order and disorder distinguishes complexity theory from the more static idea of organization-environment “fit” derived from contingency theory that is behind the integration-responsiveness grid (Prahalad & Doz, 1987) and the differentiated network (Nohria & Ghoshal, 1997). The notion of fit would suggest that the level of internal complexity would need to match the level of external complexity. In contrast, complexity theory often examines the nonlinear relationship between internal complexity and external complexity (Baum, 1999).

Self-organization is central to the view of business organizations as complex adaptive systems (CAS). In CAS, evolutionary processes emerge that cannot be directly inferred from initial conditions. Simon (1962: 468) described CAS as “made up of a large number of parts that interact in a nonlinear way. In such systems, the whole is more than the sum of the parts, …[and] given the properties of the parts and the laws of their interaction, it is not a trivial matter to infer the properties of the whole.” CAS are systems in which large networks of separately evolving subunits result in complex collective behavior and adaptation transcending the horizon of any single decision-maker. This decentralized and emergent nature parallels the challenges faced by MNCs, where subsidiaries operate across diverse national environments, each shaped by distinct cultural and institutional constraints.

For managers of MNCs, understanding that their organizations operate as CAS implies recognizing that the whole may develop into something that cannot be anticipated from the sum of its parts. Actions taken by individual subsidiaries may lead to unintended consequences for the entire corporation, as seen in the literature on subsidiary initiatives where MNC subsidiaries may even “wag the dog”: for example, the German subsidiary of IBM engineered a Linux version of the mainframe operating system that set into motion a decentralized shift across the entire corporation from proprietary to open systems in IBM mainframe software (Schmid, Dzedek, & Lehrer, 2014).

Emergence Between Competency Traps and Instability

A central concept in complexity theory is emergence, which pertains to how novel organizational behaviors, structures, or strategies arise unpredictably from interactions among individual components and external forces. While emergent phenomena can lead to innovative solutions, such beneficial outcomes are not guaranteed. In complex business environments like MNCs, certain emergent solutions can prove maladaptive, hindering rather than fostering long-term performance.

The complexity theory literature broadly identifies two common conditions under which suboptimal solutions emerge. First, organizations may fall into local optima on so-called rugged landscapes (Levinthal, 1997) – environments characterized by multiple local performance peaks that are lower than the global performance peak. In business terms, local optima represent predicaments such as competency traps, where firms become fixated on responding to specific conditions at a given time and place, optimizing for short-term gains while overlooking superior opportunities elsewhere on the landscape. Second, organizations may experience instability due to excessive reactivity to momentary environmental fluctuations. Especially in rapidly changing markets, firms that overcommit to continuous adaptation to environmental changes risk organizational fragmentation, inefficiency, and loss of strategic coherence.

Between these extremes lies the edge of chaos, a critical zone where organizations must balance stability with adaptive flexibility (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1998; Eisenhardt & Piezunka, 2011). For MNCs, operating at the edge of chaos requires simultaneously adapting to local subsidiary conditions while managing interdependencies across subsidiaries and with the external environment. This challenge can be visualized as navigating a dynamic landscape of shifting opportunities. High points on this landscape represent successful configurations of interdependent operations, while low points signify ineffective ones. The challenge for MNCs is twofold: they must identify and ascend high-performance peaks while avoiding the ‘valleys’ of poor combinations – all while recognizing that the landscape itself is not static but evolving. Complexity theory does not offer a ready-made solution for MNC managers; rather, it provides a useful framework for understanding a constantly changing environment where effective solutions must emerge organically from interactions among decentralized subunits rather than through top-down design based on tacit notions of organization-environment fit.

From Coordination to Coupling

Complexity theory envisions an organization’s environment as a dynamic landscape, continuously reshaped by interactions among the entities that populate it. The extent of this reshaping depends on the degree of coupling among an organization’s subunits, which may be subsidiaries, groups, and/or individual managers. While traditional MNC frameworks emphasize coordination, complexity theory shifts the focus to coupling. Though both involve interdependence, they differ in their assumptions and implications.

Coordination refers to the deliberate alignment of activities, resources, and decisions to achieve strategic coherence, typically through managerial control. In contrast, coupling captures mutual influence from a systemwide perspective, emphasizing emergent patterns shaped by decentralized interactions. Unlike coordination, which implies intentional design, coupling highlights spontaneous, evolving interdependencies. Tightly coupled systems exhibit strong interconnections, where changes in one part trigger significant ripple effects across others. Complexity theorists emphasize nonlinearity—a disproportionate relationship between variables, where small changes can lead to outsized, unpredictable effects. This challenges conventional policy and management thinking predicated on proportional, linearly measurable cause-effect relationships.

From the perspective of coupling, complexity theory offers two key insights to help managers balance the autonomy and collaboration of MNC subsidiaries. The first considers the subsidiary perspective, focused on achieving the optimal degree of coupling within the subsidiary’s own organization. Overly connected operations (the pull of exploitation) can become rigid and unable to adapt to new opportunities, while under-connected operations (the pull of exploration) may lack coherence and become error-prone (Eisenhardt & Piezunka, 2011). The need to achieve the right intermediate degree of system connectedness highlights the dynamic interplay between independence and interdependence that enables MNC units to evolve effectively in complex environments.

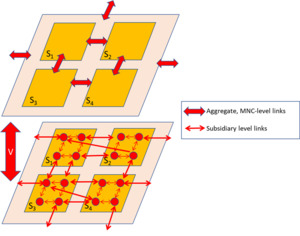

However, whether due to their own choices or as a result of MNC-level policies, subsidiaries are coupled with other subsidiaries and coevolve to varying degrees. The second key insight from complexity theory concerns the balance between internal structure and external coupling: increasing internal structure speeds up the process of reaching stable equilibria, while increasing external coupling slows it down (Baum, 1999). When a subsidiary has a weak internal structure but strong external coupling with other subsidiaries (Figure 1a), it struggles to settle on a strategy, as its solutions quickly become obsolete. Conversely, with high internal structure and low external coupling (see Figure 1b), the subsidiary quickly reaches a local performance peak (e.g., a competency trap) and remains there, even if the peak is suboptimal, because external forces are too weak to push it away.

Moreover, the landscape of an organization is continuously reshaped by interactions with the external environment, meaning organizations adapt to their own landscapes while coevolving with the environment. MNCs bring a further layer of complexity since co-adaptation in MNCs occurs at multiple levels: between subsidiaries, between subsidiaries and headquarters, and between the MNC as a whole and its external environment.

The Role of Modularity

If top-down organization design runs contrary to the tenets of complexity theory, what positive design prescriptions can the theory offer? Research suggests the selective use of modular structures. Biologist Stuart Kauffman identified conflicting constraints among system components as a key challenge in complex organizations. Using a “patch procedure” divides a complex task into non-overlapping patches, allowing each to optimize independently while the system as a whole evolves toward greater fitness (Kauffman, 1995). Similarly, Simon (1962) argued that hierarchic and decomposable systems evolve faster than fully integrated ones, making modularity a valuable approach for the design, coordination, and management of complex systems.

In the context of MNCs, modularity manifests itself as business units or subsidiaries that operate semi-independently while remaining loosely coupled through a corporate framework. This approach adds a dynamic element to the balancing of global standardization with local adaptation. Notably, modularity fosters innovation by creating a decentralized environment where subsidiaries can experiment with new ideas without excessive corporate oversight. This trial-and-error approach encourages localized adaptation, with successful innovations later scaled across the broader organization.

A prime example is Haier, the Chinese multinational that restructured around the RenDanHeYi model, transforming into a network of self-managed micro-enterprises. Haier instituted a decentralized platform-based structure, enabling its units to innovate autonomously while remaining strategically aligned through shared incentives and digital ecosystems.

Nearly Decomposable Systems and the MNC

We have yet to address the issue of hierarchy, an obviously vital characteristic of MNCs in view of HQ-subsidiary relationships. In fact, complexity theory has its own conceptualization of hierarchy. Simon (1962) introduced the concept of nearly decomposable systems (NDS), in which connections and dependencies between subunits emerge at a higher organizational level that is more than just the sum of individual units. This conceptualization highlights key issues that are of lesser interest in traditional MNC theories. One such issue is varying speeds of adaptation at different hierarchical levels.

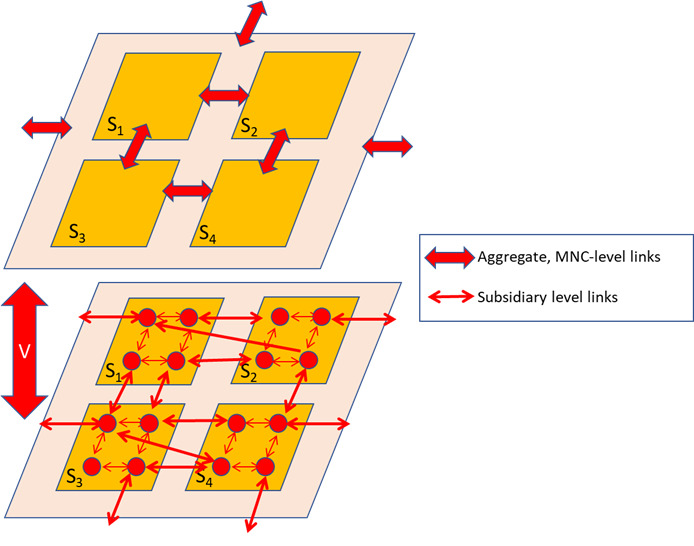

In an NDS, subunits operate relatively independently in the short run, whereas in the long run, “the behavior of any one of the components depends in only an aggregate way on the behavior of the other components” (Simon, 1962: 474). Because intra-component linkages are stronger than inter-component ones, rapid changes within individual subunits can unfold without being constrained by the slower, more strategic shifts occurring across the organization. Applied to MNCs, this suggests a two-tier model of adaptation, as illustrated in Figure 2, where local subsidiary evolution interacts with broader corporate-level strategic adjustments.

The MNC in this model is composed of four subsidiaries (S1 to S4) located in four different countries. It includes coupling mechanisms at two different levels: subsidiary (lower level) and MNC (upper level), as well as vertical linkages connecting the two levels (‘V’). At the subsidiary level, linkages can be within subsidiaries, between subsidiaries, or to the external environment (e.g., to partners or competitors). At the upper level in Figure 2, linkages within subsidiaries are no longer shown, and two types of linkages remain visible: those between subsidiaries (which are internal to the MNC but external from a subsidiary’s perspective) and those connecting the MNC to the broader external environment.

For the sake of illustration, let us suppose the linkages in this model are knowledge transfer channels. Linkages between subsidiaries and to the external environment appear at both levels in Figure 2, but their basic nature and frequency of change differ. More specifically, the linkages between subsidiaries at the lower level are knowledge transfer activities across subsidiaries, synergistic collaborations emerging from their interactions while pursuing self-interested actions. At the upper level, such linkages are not just aggregations of the lower-level linkages but rather a platform for the MNC’s long-term evolution. To take the example of IBM mentioned earlier, the IBM Academy of Technology was an organization-wide institution of top talent comprising a set of higher-level linkages beyond day-to-day business transactions which clearly contributed (and was intended to contribute) to the long-term trajectory of the entire corporation (Schmid et al., 2014).

From a complexity perspective, such linkages are not just channels for knowledge transfer in a coordination-and-control sense, but also mechanisms for coevolution. There are both quantitative and qualitative implications of this. Quantitatively, upper-level linkages can be used to encourage or restrict knowledge flows among subsidiaries. From a complexity perspective, too much exploration and knowledge sharing at lower levels can undermine organizational adaptation when interdependencies between subsidiaries are high. Therefore, the goal for the MNC is to optimize, not maximize, knowledge transfer (e.g., Celo & Lehrer, 2022) and to allow subsidiaries to learn from each other without overwhelming the organization with coordination burdens. Qualitatively, corporate-level knowledge transfer differs fundamentally from subsidiary-level exchange, shaping strategy rather than just operations. This distinction is exemplified in the case of Geely and Volvo.

The NDS Example of Zhejiang Geely and Volvo

The concept of nearly decomposable systems (NDS) provides a lens for understanding how MNCs manage the tension between fast-paced, localized dynamics within subsidiaries and the slower, more strategic changes at the corporate level. Zhejiang Geely’s acquisition of Volvo in 2010 (Jonsson & Vahlne, 2023) highlights the difference between corporate-level and subsidiary-level knowledge transfer. At the subsidiary level, knowledge exchanges were largely technical and operational, occurring between Volvo and Geely engineers through specific, project-based collaborations like the Compact Modular Architecture (CMA) platform.

However, corporate-level learning was more strategic and systemic, focusing not just on acquiring knowledge but on “learning how to learn” (Jonsson & Vahlne, 2023: 701). This effort led to the establishment of China Euro Vehicle Technology (CEVT) in 2013—three years after the acquisition. Initially, Geely had kept Volvo and Geely Auto separate to protect Volvo’s knowledge base and intellectual property, but as top corporate management recognized the need for deeper learning, CEVT was created as a neutral hub to create higher-level knowledge among Swedish and Chinese engineers about just what it was that they could learn from one another.

This distinction between subsidiary-level knowledge transfer and corporate-level learning illustrates a basic tenet of the NDS framework. While subsidiary interactions were frequent and project-driven, corporate learning involved slower, structural adaptations that reshaped how Geely managed complexity. Rather than imposing rigid hierarchical control, top management allowed cooperation between Geely and Volvo to evolve in such a way that, with time and patience, new capabilities emerge at the corporate level. Jonsson & Vahlne (2023: 701) documented the conviction of Geely’s top management that “complexity should not be understood as a risk, or uncertainty, to be avoided or controlled, but rather as something that should be embraced, as it offers opportunities to learn and to perform business in new innovative ways.”

Strategic Implications for MNC Management

Viewing MNCs as complex adaptive systems (CAS) requires a fundamental shift in how managers approach strategy and organizational design. Traditional frameworks emphasize coordination and control, tacitly assuming that complexity can be managed through some optimally designed network structure achieving organization-environment “fit.” However, complexity theory suggests that emergence, self-organization, and decentralized evolution are the primary forces shaping an MNC’s long-term performance – processes that cannot be fully masterminded from the top.

The case of Geely and Volvo illustrates one basic way that MNCs can navigate complexity: by fostering distinct but intertwined learning processes at different levels. Rather than imposing immediate integration, Geely allowed Volvo to operate autonomously, respecting its existing knowledge base while gradually introducing higher-level platforms, such as CEVT, to facilitate knowledge exchange. This approach enabled Geely to develop learning capabilities at the corporate level, allowing subsidiary-driven technical knowledge flows to be complemented by emergent corporate-level capabilities. For MNC managers, such an approach underscores the importance of developing adaptive mechanisms that facilitate higher-level learning, ensuring that cross-unit learning enhances strategic evolution without constraining local adaptation. In this way, MNCs can harness complexity rather than being overwhelmed by it.

Ultimately, complexity theory reframes MNC management as the challenge of orchestrating decentralized evolution. Rather than seeking optimal controls and structures, managers must cultivate conditions and platforms that allow the MNC to self-organize even at the corporate level. This requires a mindset shift – from controlling complexity to harnessing it as a source of opportunity and competitive advantage.

Conclusion: Managing Complexity in MNCs

MNCs are inherently complex, adaptive systems operating in a constantly changing global environment. By embracing the principles of CAS, managers can better navigate the challenges of managing across multiple countries, cultures, and institutional contexts.

In this context, the role of managers is not just to find momentary tradeoffs between local differentiation and global integration within the MNC organization, but to create the conditions for corporate adaptation and decentralized MNC evolution. By understanding MNC dynamics as CAS, managers can develop more effective strategies for managing complexity and ensuring long-term success.

Embracing complexity theory and viewing the MNC as a CAS goes beyond merely reorganizing its components and connections, or suggesting that the MNC simply resembles a CAS. The crucial insight is that the MNC must actually operate as a CAS and use the principles of self-organization, emergence, and adaptability to navigate the unpredictability of the global business environment.

About the Authors

Sokol Celo is Professor of Strategy and International Business at Suffolk University in Boston, Massachusetts. His areas of expertise include MNCs as complex adaptive systems, international location decisions, cognition and managerial decision making, and institutions and institutional change. He is a member of the Academy of International Business and has published in the Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Business Research, Journal of International Management, International Business Review, Journal of World Business, and Socio-Economic Review, among others.

Mark Lehrer is Professor of Strategy and International Business at Suffolk University. He obtained his PhD in Management from INSEAD after previously studying at MIT and the University of California in Berkeley. His publications cover the topics of R&D, innovation, political economy, and multinational corporations. Journals in which he has published multiple articles include California Management Review, Organization Studies, Journal of World Business, Journal of International Management, International Business Review and Research Policy.