The accumulation of rare but impactful events in recent years, including the Covid-19 pandemic, climate-related disasters, and the rise of artificial intelligence, suggests that we live in an Age of Disruption. Fueled by the heightened interconnectivity of human activity, such events are arising with increasing frequency and severity (Beamish & Hasse, 2022). One implication thereof is that any preconceived certainties regarding what is known (and knowable) are eroding. Today, new information is easy to generate and quick to expire, a commodity that is contested, fragmented, and contextual – or entirely non-existent. This creates significant challenges for leaders operating in international business (IB) settings. As a recent survey of 3,100 large global companies revealed, many CEOs today find themselves in a state of acute anxiety, whereby 65 percent reported being highly disrupted in the past year and 58 percent worried they are falling behind the knowledge and skill curve (AlixPartners, 2024).

Surely, there are opportunities emerging from some of these disruptions, such as greater scope and accessibility of content, as well as new business models and sources of competitive advantage. As IB educators preparing current and future leaders for complex decision making under vast uncertainty, however, we ought to be particularly cognizant of the downside risks. Most disruptive forces span beyond the geographical, temporal, and functional boundaries that typically confine management education, as the literatures on grand challenges (George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, 2016), wicked problems (Lönngren & van Poeck, 2021; Rašković, 2022), and natural disasters (Oh & Oetzel, 2023) underscore. Many educational approaches optimized for knowledge accumulation on narrowly defined phenomena prevalent during stable times simply do not apply in today’s environment. Moreover, the force with which these disruptions unfurl upon communities necessitates that we also impart moral considerations upon learners.

Informed by my research and teaching on rare/impactful events, I thus propose a pedagogical approach suitable for this Age of Disruption. Few disciplines are thereby as well-equipped to address boundary-spanning and rapidly evolving phenomena as IB, given our field’s emphasis on context, connection, and complexity (Dau, Beugelsdijk, Fleury, Roth, & Zaheer, 2022). Central to the approach is a conceptual extension of Bloom’s taxonomy (in its updated version by Krathwohl, 2002) to encompass dynamism within the knowledge environment. This results in the formulation of a “fire-mindset” approach, characterized by six principles across the metaphorical elements of “Spark,” “Stoke,” and “Sustain.” Importantly, I also introduce a growing repository of original research and teaching materials on rare and impactful events, made available to IB scholars and educators. Adapting our pedagogical approaches to current realities ought to be a top priority, given that disruptive events do not care whether we are sufficiently prepared – we, however, should.

Pedagogical Conundrums Arising in an Age of Disruption

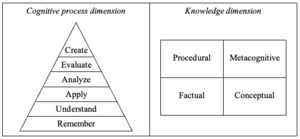

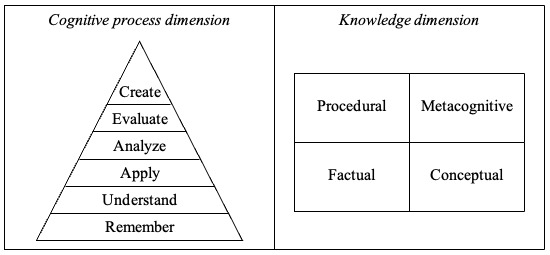

Pedagogical frameworks have guided educational approaches for decades, whereby Bloom’s taxonomy has been amongst the most influential. In its revised form (Krathwohl, 2002), the taxonomy suggests that learning objectives can be organized along two dimensions. The cognitive process dimension approximates a cumulative hierarchy, such that the first two levels (remember, understand) precede and are iterated with more complex cognitive processes (apply, analyze, evaluate, create). The knowledge dimension, in turn, ranges from factual (terminology, specific details), conceptual (classifications, categories, principles, generalizations, theories, models, structures), and procedural (subject-specific skills, algorithms, techniques, methods) to metacognitive elements (strategic knowledge, knowledge about cognitive tasks, contextual and conditional knowledge, self-knowledge). Although they are visualized in Figure 1 below as distinct dimensions for purposes of clarity (and as a foundation for Figure 2), they intersect in capturing the complexity of learning.

Underpinning Bloom’s taxonomy is thereby an assumption of stability, presupposing that relevant knowledge exists which can be accumulated and consolidated. While this remains true for some types of knowledge (e.g., accounting rules), the dynamic complexities characterizing disruptive times create unique pedagogical conundrums especially pertaining to strategic decision making in global business contexts. First, heightened levels of randomness and little pre-existing data on rare/impactful events vastly increase associated degrees of freedom, rendering past insights largely irrelevant and future predictions largely inaccurate. Yet, how are educators to prepare decision makers for events that have not (yet) materialized, conveying knowledge that does not (yet) exist? Second, the scale and trajectory of a disruptive event’s impact often transpires in nonlinear ways, e.g., exponentials or time-delayed cascades (Hasse, 2024). Yet, how are educators to facilitate learning, if information is rapidly and unexpectedly evolving, curtailing periods of knowledge consolidation? Third, a catalyst behind many disruptive events is the increasing interconnectedness of human activity (Beamish & Hasse, 2022). This systemic complexity, spanning beyond political and cultural boundaries, creates power law effects which amplify the frequency and impact of these events. Yet, how are educators to cover the systemic effects of disruptive events within the realities of business school curricula? Finally, we are not wired to grasp rare non-linear events intuitively, instead underestimating the impact of exponential trajectories and misestimating contextual rarity. So, how are management educators to convey insights about a phenomenon if the understanding thereof is impeded by evolutionarily inbuilt biases?

While exhaustive answers to these conundrums lie beyond the scope of this article, I offer in the following a framework which provides a pedagogical starting point. It is most straightforwardly applicable to IB-related courses, which typically offer wider lenses than function-specific courses, though it also holds value for those.

A Guiding Framework

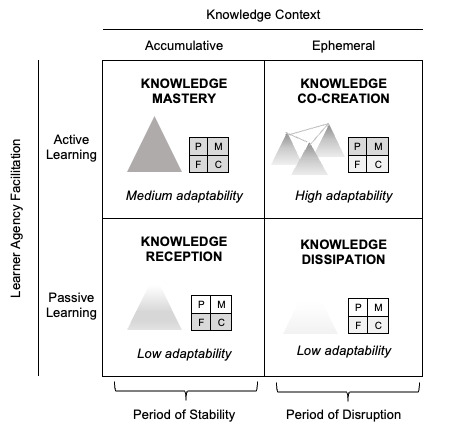

Given the above, IB educators must account for the extent to which knowledge is accumulable (period of stability) versus ephemeral (period of disruption). The effectiveness of pedagogical approaches is thereby impacted by learner agency facilitation, reflecting a degree of ephemerality of knowledge in the learner. Juxtaposing these dimensions reveals four distinct learning outcomes (Figure 2), each with relative emphases along Bloom’s taxonomy as implied by the shaded areas.[1]

Knowledge Reception

Passive learning approaches within an accumulative knowledge context are represented by the traditional “sage-on-the-stage” model of knowledge transmission. Learning objectives focus, relative to other quadrants, on remembering and understanding factual and conceptual knowledge, resulting in knowledge reception, albeit with little integration, skill development, or creative elements. This has a limiting effect on learning outcomes, reflected in lower effectiveness scores for traditional lecturing classes compared to those with active learning approaches (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018).

Knowledge Mastery

In contrast, active learning approaches (e.g., cases, simulations, transformative learning experiences) in an accumulative knowledge context facilitate learner agency which fosters the development of integrative subject mastery. Relative to other quadrants, learning objectives under these conditions emphasize Bloom’s cognitive processes relatively evenly across all knowledge types. Such approaches produce favorable learning outcomes (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018) but presuppose that relevant knowledge exists and can in fact be consolidated.

Knowledge Dissipation

During periods of disruption, Bloom’s knowledge types remain important, although a juxtaposition with the Knowledge Reception quadrant reveals an overall less effective activation (as indicated by the fainter color saturation). Factual/conceptual knowledge, for instance, becomes more incomplete and uncertain, while “remembering” and “understanding” become less available or reliable especially where they are outsourced to artificial intelligence, which in turn impedes higher-order learning. The shortcomings of passive learning are exacerbated under these conditions, such that the lower degree of individual agency can make the learner prone to distractions and misinformation.

Knowledge Co-creation

Active learning approaches during periods of disruption can alleviate some of the aforementioned challenges, if they are focused on cultivating procedural/metacognitive knowledge and developing co-creative knowledge networks across learners. Systems-thinking and adaptive resilience thus take on greater importance during disruptive times, compared to comprehensive proficiency incentivized during stable times. As a result, the relative emphasis in Bloom’s implied hierarchy becomes (to some extent) inversed, as indicated by the shading in Figure 2, empowering learners to engage in metacognitive reflections and curiosity-driven knowledge discovery.

In sum, the proposed framework expands Bloom’s taxonomy by highlighting dynamism within the knowledge environment, thus exposing relative emphases regarding cognitive processes and knowledge types, as well as the importance of networked learning. The essence of empowered “knowledge co-creation” as a pedagogical approach is thereby reflected in the Greek philosopher Plutarch’s adage that “the mind is not a vessel to be filled - but wood that needs igniting, [motivating] one towards originality and [a] desire for truth” (Waterfield, 1992: 50). Hereafter, moving from “why” and “what” to “how,” I thus refer to the approach as the “fire-mindset.” Given the context, FIRE thereby also serves as an acronym for “Future-ready teaching” about Impactful Rare Events, incorporating Dieleman, Šilenskytė, Lynden, Fletcher, and Panina’s (2022: 190) pedagogical terminology.

The Fire-Mindset in Action

Determining learning objectives when designing courses, sessions, and assignments requires prioritization. While all knowledge types and cognitive processes matter within Bloom’s taxonomy, the facilitation of a “fire-mindset” places a relatively higher emphasis on the empowered co-creative activation of procedural/metacognitive knowledge and higher-order cognitive processes. This is not to imply that “remembering” and “understanding” factual and conceptual knowledge is obsolete (which would be a dangerous proposition) – but rather that higher-order dimensions must be especially engaged for their stabilizing effect during highly uncertain times. To guide such a pedagogical approach, it is helpful to discern key principles along three interlinked elements which I label, in keeping with the metaphor, “Spark,” “Stoke,” and “Sustain.”

Below, I detail each principle along the three elements, illustrated by an example of a course design for a graduate-level elective on lower-income (frontier) markets. These markets tend to face greater levels of uncertainty, volatility, and unpredictability and are often more impacted by rare events than higher-income markets. The course was designed during the Covid-19 pandemic, which inspired further encouragement of agile decision making under vast uncertainty. I first taught the course, which consists of 10 three-hour sessions, at a North American university in 2021, having since utilized all modes of delivery (virtual, hybrid, in-person). Classes have been diverse, with substantive numbers of international students.

Naturally, a more comprehensive description of the fire-mindset approach, along with detailed applications, extends beyond the scope of this article. To encourage continued engagement among IB scholars and educators, and in recognition of a dearth of centralized original research and teaching resources related to the Age of Disruption, I thus launched “The RARE Initiative” (available at TheRareEventsLab.com). In addition to research insights, the teaching materials available there range from downloadable course activities to teaching cases, content for syllabi, and reading materials, with new materials being added at regular intervals. I thus encourage readers of AIB Insights to peruse the website for further detail and inspiration.

Element I: Spark

Principle 1: Fostering curiosity through safe experimentation and multisensorial engagement.

-

Description: The initiation of a “spark” is crucial to activating a fire-mindset. To make a spark jump, an effective way is to present intentionally perplexing dilemmas related to rare and impactful events. Once learners are confronted with such a dilemma, e.g., case conundrums, ranking exercises, polling activities, or evidence-based paradoxes, a chain of reflections ensues that leads to the uncovering of biases, engagement with others, and new ways-of-thinking (Hasse, 2022). Especially impactful are those activities that engage multiple senses, thus stimulating interest and further experimentation – an ideal starting point for a subsequent in-depth exploration of the subject.

-

Course Design Example: While the course overall follows the conceptual arc of the cultural adaptation curve, each session within this arc is designed to begin with a course activity that presents a perplexing dilemma (see Table 1 for two concrete examples). The objective is to spark curiosity for the academic discussion that follows thereafter.

Principle 2: Cultivating critical thinking through the elevation of information- and bias-literacy.

-

Description: Given that the knowledge context during disruptive times tends to be more ephemeral than during stable times, the ability to discern the quality of information becomes crucially important. Activities and discussions that advance learners’ metacognition regarding information literacy and their own biases can be useful pedagogical approaches to that end. Learners are guided to reflect upon what is unknown (and unknowable) and complement the skill of developing better answers with that of asking better questions.

-

Course Design Example: In addition to the activities mentioned in Principle 1, the textbook for the course (Rosling, 2018) is deliberately chosen to not only advance students’ knowledge about course topics but to do so from the perspective of what Rosling calls the 10 “instincts.” Each session covers one of these biases and derives implications for strategic decision making. Additional activities and discussions to further information- and bias-literacy are distributed throughout each session.

Element II: Stoke

Principle 3: Embracing ambiguity, complexity, and polytely.

-

Description: Once a fire-mindset has been kindled, the instructor can “stoke” it though carefully curated materials and guided discussion which elevates learners’ appreciation for ambiguity, complexity, and polytely (i.e. the simultaneous presence of multiple and often conflicting goals; Rašković, 2022). While teaching cases are an effective way to do so, simulations, formal debates, cross-disciplinary readings, and guest speakers are similarly suited to help learners surpass conventional silos.

-

Course Design Example: Teaching cases are an integral part of each session, taking up about half of the discussion time. These are complemented by research papers, managerial articles, textbook chapters, formal debates, Socratic dialogues, and widely representative guest speakers (e.g., an expert in subsistence marketplaces, member of the military, and retired ambassador). Students are encouraged to consider accuracy over perceived certainty (e.g., by stating “I don’t know”) and become comfortable with ambiguity.

Principle 4: Reflecting upon moral imperatives and ethical considerations.

-

Description: The knowledge contexts that characterize disruptive times exacerbate the need to reflect upon the moral imperatives and ethical considerations that underlie strategic decision making (including decisions that lead to non-action).

-

Course Design Example: The course is designed to foster a safe learning environment, which subsequently allows for reflections regarding moral imperatives and ethical considerations. In conjunction with the other principles, students are encouraged to take on different perspectives (e.g., through a stakeholder analysis, formal debate, or case discussion) and consider implications with nuance.

Element III: Sustain

Principle 5: Empowering autonomous answer discovery.

-

Description: To “sustain” a fire-mindset, it is necessary that the onus of maintaining the motivation to learn becomes anchored within the learner, given that information tends to require continuous updating in ephemeral knowledge contexts. This principle presupposes the incorporation of Principle 2.

-

Course Design Example: In addition to imparting upon students frameworks and facts (a deductive approach), the course design also incorporates activities which deliberately present students with a question, problem, or challenge. Utilizing their discerning and critical thinking skills (in line with Principle 2), students are then empowered to discover the answer autonomously and collaboratively (an inductive approach). This includes in-class small group activities using publicly available datasets and individual as well as group assignments.

Principle 6: Elevating cross-links and fostering global awareness.

-

Description: Fundamental to the fire-mindset approach, and spanning across all elements and principles, is the notion of empowered co-creation of knowledge. During disruptive times, it becomes even more imperative than during stable times to complement the knowledge embedded within each individual with the web of knowledge that exists across individuals. Thus, learners are guided to recognize the value but also boundaries of their own knowledge and rigorously develop knowledge networks that foster global awareness.

-

Course Design Example: Learning activities within the course are designed to be highly interactive and span across disciplinary boundaries, complementing Socrates dialogues with small-group tasks and experiential exercises that require collaboration.

The efficacy of these principles in designing the described elective is supported by its reception. Multiple student comments have highlighted the transformative and empowering nature of this pedagogical approach (“the most important thing about this course was that it completely changed my perspective of the world and it’s something I am going to take with me throughout my career” (MSc, 2021); “this course […] has positively changed my mindset on the world” (MSc, 2025); “[learning about biases] will really change my thought process going forward” (MSc, 2025). It has been recognized with teaching excellence awards (based on student nominations) every year since its inception and was a finalist for the 2021 AIB Teaching Innovation Award.

Implementation across Educational Contexts

The adaptation of educational approaches may, of course, be met with academic realities. The principles presented above are informed by my experience researching rare and impactful events and teaching undergraduate and graduate courses at two North American universities, and I was granted considerable autonomy regarding course design and delivery decisions. Some factors can affect implementation in other educational contexts. Large class sizes (especially at the undergraduate level), for instance, incentivize conventional lectures, which remain the dominant form of instruction in business schools (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018). Relatedly, resource constraints may hamper the adoption of active learning approaches which require access to copy-righted or otherwise costly materials. Moreover, cultural differences in teaching and learning styles may cause the described approach to be most directly applicable to student-centric contexts.

Yet, options exist for facilitating fire-mindsets across various educational contexts. Many active learning methods and co-creative knowledge approaches (such as the examples provided in Table 1) can be adopted in large classrooms across educational levels, delivery modes, and cultural contexts at little to no cost. It is not necessary to design a whole course along the six principles; students will benefit from being exposed to empowered co-creation within the context of a specific session or activity, so long as it encourages further curiosity and metacognitive engagement. Moreover, given the time- and resource-constraints faced by IB educators, knowledge-sharing initiatives within our scholarly community will be particularly beneficial moving forward. To that end, the website mentioned above is designed to disseminate research and teaching materials suitable for the Age of Disruption at no cost where possible and create crosslinks between IB scholars. This can be complemented with additional efforts aimed at alleviating some of the inequalities in resource endowments across educational contexts, such as the 39 Country Initiative at the Ivey Business School (Western University) which makes business cases and teaching materials freely available to university faculty and students in the world’s lowest-income countries.

More broadly, the educational context itself is changing rapidly during these turbulent times. Especially the growing ubiquity of artificial intelligence, itself an unknowns-producing technology, impacts how we interact with knowledge. Although artificial intelligence can play a role in knowledge co-creation, tools currently available tempt learners and educators alike to oversimplify the learning process (e.g., condensing nuanced text into infographics) and thus risk turning “learning” into a sleek product. Yet, it is through the persistent wrestling with complex issues that we grow – making the encouragement of empowered, critical, and globally aware thinking (as in fire-mindsets) evermore salient.

Finally, a defining feature of disruptive events is that they span across disciplines, compelling us to consider how phenomena link across economic, social, and environmental concerns (e.g., zoonoses). As IB educators, we are well-positioned to drive a paradigm shift toward co-creative systems-thinking. Aristoteles’ concept of paideia (training and education of the whole person, encompassing knowing, doing, and being) offers a promising model for such cross-disciplinary education beyond the course-level. Several institutions (e.g., Southwestern University, University of Pennsylvania) have already embraced this approach, and I encourage more administrators and educators to do so.

Conclusion

In 2019, PwC published a global survey of 2,084 senior executives, revealing that only 11 percent of organizations had devised rigorous crisis response plans – less than a year before the SARS-CoV-2 virus caused a global pandemic. Disruptive events are in part so impactful because we often are not sufficiently prepared or agile enough to address them effectively. Let us change that, one fire-mindset at a time.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefitted greatly from thoughtful comments provided by AIB Insights editor Matt Rašković and two anonymous reviewers. I am also grateful for input from members of the teaching innovation award committee at the AIB Teaching & Education Shared Interest Group, attendees of the Teaching Café at 2025 AIB Louisville, as well as the students I have taught and learned from throughout the last decade.

Vanessa C. Hasse is an Assistant Professor of International Business at the Ivey Business School, Western University (Canada). Her current research focuses on organizational responses to performance signals and outlier events in international contexts, with a particular focus on rare and impactful events. She has published in Academy of Management Journal, Global Strategy Journal, Business & Society, and more. As a management educator, she has authored several case studies and been recognized for her innovations in designing transformative learning experiences.

Please note that differences in pyramid sizes are merely for purposes of visualization.