Introduction

The global energy transition and the fight against climate change rely heavily on critical minerals, which are integral to technologies such as lithium-ion batteries (IEA, 2023). We focus on critical mineral investments in Latin America which is rich in minerals including copper, lithium, nickel, and zinc. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (2025), Chile and Peru account for over 34% of global copper production in 2024, while Chile, Argentina, and Brazil contribute 32% of global lithium production, and the “Lithium Triangle” (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile) holds 49.6% of global lithium resources—far surpassing the U.S. (16.5%), Australia (7.7%), and China (5.9%).

The strategic importance of critical minerals has subjected them to geopolitical rivalries, most notably between the U.S. and China (Ufimtseva, Li, & Shapiro, 2024). Latin America’s resource wealth has made it a focal point of this competition. Simultaneously, some governments in Latin America increasingly adopt nationalist policies such as state ownership to maximize economic benefits.

We examine critical mineral investments in Latin America through the dual lenses of geopolitical rivalry and resource nationalism, drawing on a firm-level dataset of mining activity.[1] Our analysis compares U.S. and Chinese strategies toward critical minerals and assesses their implications for MNEs, while also evaluating how host country policies shape investment decisions. Figure 1 illustrates how geopolitics and domestic policies interact to influence firm behavior.

Critical Minerals in Latin America: Data

We first analyze critical mineral investment patterns using the U.S.-defined list of critical minerals (Figure 2A).[2] Among foreign investors, Canada has established itself as the dominant player in Latin America, owning 35% of critical mineral mines in 2023, followed by the U.S. (16%), Australia (12%), the United Kingdom (10%), and China (9.6%). Latin American companies remain significant, with Peru and Chile accounting for 10% and 12% of mines, respectively.

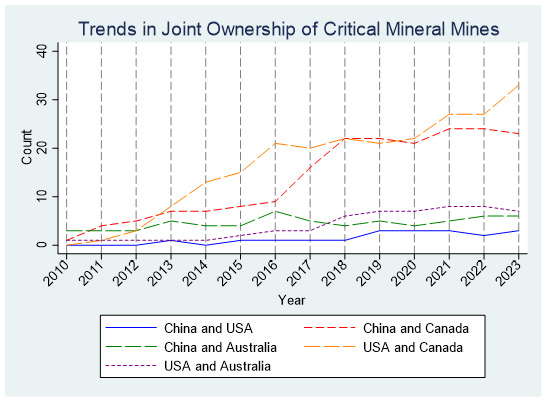

Figure 2B shows a surge in Canada–China collaborations in Latin American critical mineral projects from 2016 to 2018, followed by a plateau. In contrast, Canadian–U.S. partnerships have grown since 2020. These trends suggest that U.S.-China rivalry and Canada’s alignment with U.S. strategy influences cross-border collaborations among firms from allied or competing nations.

Lithium investments (116 mines) show a somewhat different pattern. In 2023, Canada led with 42% of lithium mines, followed by China (24%), Australia (20%), and the U.S. (17%). While China is not yet a dominant player in Latin America’s broader critical mineral sectors, it has become a leading investor in lithium. Figure 3 shows steady Chinese expansion since 2015, likely reflecting the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China’s strong electric vehicle (EV) and battery industries, which incentivize Chinese firms to pursue lithium opportunities.

The presence of domestic firms in lithium, however, is limited. For example, firms from Chile, the top regional contributors, account for only 6 of the 116 lithium projects. This limited role helps explain why some Latin American countries have embraced resource nationalist policies, as governments seek greater state control over strategic resources.

Overall, Figures 2A and 3 highlight Canada’s consistent leadership in Latin American critical minerals, from 2010 to 2023, reflecting Canadian firms’ long-standing position in the region and their firm-specific advantages in addressing regulatory, environmental, and community challenges.

China’s BRI Strategy

China’s BRI has played a pivotal role in facilitating Chinese investments in Latin America’s critical mineral sectors and is often cited as a successful long-run strategy that combines infrastructure support, resource access, and diplomacy (Yu & Sabatini, 2024). By 2022, 20 countries in the region had joined the BRI, benefiting from Chinese infrastructure projects and concessional loans that have strengthened diplomatic ties and enabled resource access (Roy, 2023). These diplomatic relations have been key to securing operating licenses, reducing political risks, and creating favorable conditions for Chinese investments in critical minerals. Furthermore, China’s dominance in EV supply chains provides additional advantages for Chinese firms, as they integrate upstream mineral extraction with midstream processing and downstream battery and EV production. This integrated strategy positions China as a global leader in the energy transition and represents firm-specific advantages that firms can explore in host countries.

An example of China’s approach is Bolivia, where Chinese firms have gained a strong foothold in the critical minerals sector. In 2015, Bolivia secured $7.5 billion in loans from China’s Export–Import Bank, promoting Chinese involvement as contractors and investors. Bolivia later partnered with a Chinese consortium to build lithium extraction plants. These partnerships, following the cancellation of a prior German deal, reflect Bolivia’s growing preference for Chinese investment under the BRI framework. Nonetheless, as discussed later, the BRI’s influence remains limited, as project success also depends on securing the support of non-government stakeholders, including environmental groups.

The U.S. Strategic Approach

It is argued that the U.S. has ignored Latin America for decades, although that may be changing (Winter, 2024). The U.S. has to date adopted a combination of domestic regulations and alliance building to secure critical mineral supply chains and counter China’s dominance (Ufimtseva et al., 2024). Although these are not directed specifically at Latin America, they can affect MNE investments in Latin America.

Domestic Regulations and Free Trade Agreements

Under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, to be eligible for clean energy benefits in the U.S., the firm must use critical minerals extracted or processed in the U.S. or countries with free trade agreements (FTAs) (Federal Register, 2024). Such FTAs are relevant to Latin America as countries like Chile, Peru, and Mexico have such agreements with the U.S. The IRA excludes firms classified as Foreign Entities of Concern (FEOCs), defined as those with 25% or more ownership by governments or entities from adversarial countries like China. The 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) expands this definition, disqualifying a broader range of China-linked firms from receiving U.S. benefits (Baskaran & Schwartz, 2025). These restrictions may shape MNE investment strategies in Latin America, especially for companies aiming to serve the U.S. market, as they may seek to avoid partnerships involving Chinese ownership.

International Alliance Strategy

The U.S. has complemented its domestic policies with an alliance-building strategy designed to enhance critical mineral supply chains. A key component is the promotion of its stringent foreign direct investment (FDI) regulations, such as the 2018 Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), to allies like Canada and Australia. FIRRMA expands U.S. regulatory oversight of foreign investments in strategic sectors, especially those involving Chinese firms, effectively deterring Chinese acquisitions of critical mineral assets in the U.S. Since 2020, Canada and Australia have adopted similarly restrictive FDI policies, resulting in several rejections of Chinese investments in critical mineral projects (Li, Shapiro, & Ufimtseva, 2024).

Another pillar of the U.S. alliance strategy is the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), launched in 2022 with 15 mainly developed-country allies such as Canada, Australia, Japan, and several in Europe.[3] The MSP aims to diversify mineral supply chains and uphold high ESG standards. To engage resource-rich developing countries, the MSP Forum was created in 2024, with participants including Argentina, Peru, Mexico, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic. The Forum promotes policy dialogue and investment cooperation in mining and processing, but unlike China’s BRI, the MSP appears to lack direct state-led financing, which may limit its ability to compete with China’s more capital-intensive approach.

There is no formal evidence that the U.S. conditions FTAs or MSP participation on limiting Chinese involvement; for example, Chile works closely with Chinese firms despite a U.S. FTA, and Argentina’s 2024 MOU with the U.S. on critical minerals includes no China-specific exclusions. All three Lithium Triangle countries maintain growing ties with China under the BRI.

Impact on Firms

While not directed at Latin America, U.S. policies can significantly influence firm strategies there. A notable example is Lithium Americas, a Canadian company that split into two entities: one focused on North America, where China’s Ganfeng holds no direct stake—aligning with U.S. IRA sourcing rules—and another on Argentina, where Ganfeng maintains significant ownership in lithium projects.[4] This example demonstrates how Canadian MNEs adapt their strategies to align with U.S. policies when targeting the U.S. market. Similarly, we expect that IRA and OBBB rules likely discourage U.S. and allied MNEs from collaborating with Chinese partners when serving the U.S. market. This tendency may be especially pronounced in countries with FTAs with the U.S., such as Chile, Peru, and Mexico, as MNEs may aim to leverage preferential access to the U.S. market.

Chinese MNEs face growing hurdles from restrictive FDI regulations in countries like Canada, which have aligned with U.S. geopolitical strategies in critical minerals, ordering three Chinese state-owned firms to divest their shares from Canadian lithium companies in 2022. These cases highlight the declining appeal of Chinese firms as partners for MNEs targeting U.S. and allied markets. Still, Figure 2B shows that joint Canadian–Chinese ownership in Latin American mines has remained stable since 2018, suggesting that firm strategies are shaped by both geopolitical and economic considerations. While firms are cautious about expanding such partnerships, they generally maintain existing ones unless compelled to withdraw by government orders.

Host Country Strategies

Latin American countries have adopted diverse strategies toward their critical mineral sectors, ranging from resource nationalism favoring state control to open-market models that encourage FDI. Most respond to U.S.–China geopolitical rivalry by pursuing a balancing approach, while others, like Bolivia, align more closely with China. These policy choices shape how MNEs engage across the region. Rather than offering a comprehensive analysis, we highlight representative country examples to illustrate each policy type.

Nationalist Policies: Chile, Bolivia

In 2023, Chile launched its National Lithium Strategy, expanding state control over the lithium sector by creating the state-owned National Lithium Company to oversee industry development. A key example is the Codelco-SQM joint venture, where state-owned Codelco now holds majority ownership, reducing SQM to a minority role. This shift diminishes the influence of China’s Tianqi, which has about 24% stake in SQM, now relegated to a passive financial role.[5] Despite increased state control, Chile actively courts both U.S./allied and Chinese investment, using geopolitical competition to strengthen its lithium value chain. The 2024 “Chilean Call” targets U.S. private-sector partnerships, while ChileWeek China 2023 saw President Boric meet with Tsingshan Group to discuss lithium battery investment.

Chile’s lithium is primarily extracted from brine in the Salar de Atacama and processed into lithium carbonate. Production is dominated by SQM and U.S.-based Albemarle. However, lithium carbonate sits low on the value chain compared to higher value-added products like cathodes and batteries. To promote industrial upgrading, Chile’s development agency, Corfo, selected Chinese firms BYD and Tsingshan in 2023 to build cathode and battery plants, with commitments to local hiring and technical training. Yet by 2025, both projects were paused due to falling lithium prices that undermined the appeal of Corfo’s incentive scheme (i.e., guaranteed purchases from SQM at pre-specified prices), along with regulatory delays and disagreements over project implementation, according to the firms involved. These setbacks highlight the limits of using FDI to promote industrial upgrading, even when bilateral ties are strong, Chinese BRI diplomacy is active, and investor–host government objectives initially appear aligned.

Bolivia has adopted a state-led strategy for lithium industrialization. A 2008 presidential decree prioritized the industrialization of the Salar de Uyuni, a vast salt flat believed to contain the world’s largest lithium reserves. In 2017, the government created Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) to oversee the entire lithium value chain. To accelerate development, YLB partnered in 2023 with a Chinese consortium called CBC—including battery manufacturer CATL, recycler Brunp, and mining firm CMOC—to build two plants using Direct Lithium Extraction, a newer technology that bypasses evaporation ponds to obtain lithium carbonate. Another partnership is underway with China’s Citic Guoan. Together, these initiatives reflect Bolivia’s strategic alignment with China in advancing its lithium ambitions, though the October 2025 election could shift the country’s stance on lithium policy and its position in the U.S.–China rivalry.[6]

Open Market Policies: Argentina, Peru

Argentina follows an open-market approach to lithium, with streamlined federal rules and decentralized provincial control, making it the region’s top destination for FDI. It hosts over half of Latin America’s foreign lithium projects, attracting firms from China, the U.S., Canada, Australia, South Korea, and Europe. Balancing pragmatism with shifting geopolitics, Argentina continues strong provincial ties with Chinese firms, especially in Jujuy, while President Milei’s pro-U.S. administration promotes deregulation and closer alignment with U.S./allied partners (Lewkowicz, 2025). This dual-track strategy allows Argentina to engage both geopolitical blocks in its critical minerals sector.

Peru maintains open-market regulations that attract investment. A law in 2021 declared lithium exploration and industrialization of national interest, though concrete policies remain limited. Peru has attracted critical minerals investment from the U.S., Canada, and China, with Chinese investment rising notably since the 2009 Peru–China FTA. Projects like the China-financed Chancay port and operations by firms like Chinalco and Zijin Mining underscore China’s expanding role in Peru’s copper sector (Nicholls, 2025).

Implications for MNE Managers

MNE strategies in Latin America’s critical minerals sector are shaped by U.S.–China rivalry and host country regulations. Table 1 summarizes major issues and recommendations. Foreign MNEs, regardless of origin, should align with Latin American governments’ growing expectations for value creation beyond extraction, including processing, battery production, and technology transfer. Most Latin American countries have maintained a geopolitically neutral stance amid the U.S.–China rivalry. MNEs should generally do the same, except when serving the U.S. market, where compliance with U.S. policies and limited cooperation with Chinese firms are essential.

Chinese MNEs should leverage BRI opportunities but recognize that BRI mainly opens doors; sustained success depends on market conditions, effective negotiations with host governments, and constructive engagement with non-governmental stakeholders, including environmental and Indigenous groups. For instance, Bolivia’s YLB–CBC consortium project, despite government approval, was recently suspended pending additional environmental review and community consultation. The two paused projects in Chile highlight how commodity price fluctuations and firm–host-government negotiations shape project outcomes. Chinese MNEs should therefore balance diplomatic goodwill with sound commercial strategies and active stakeholder engagement, while avoiding overreliance on the BRI framework.

U.S. and allied MNEs can leverage the MSP to pursue collaboration opportunities within allied countries but should avoid overreliance on policy initiatives, as the BRI experience shows their limited impact. They can differentiate through strong ESG performance and stakeholder engagement, while Chinese MNEs can leverage EV supply chain strengths to form integrated consortia across mining, processing, and battery manufacturing that align with host governments’ industrial upgrading goals. These complementary strengths create opportunities for selective collaboration between U.S./allied and Chinese firms. While geopolitical dynamics will continue to influence investment patterns and encourage cooperation within friendly blocs, economic fundamentals and complementary capabilities may still justify co-location or partnership with Chinese firms in Latin America’s critical minerals sector.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge with deep respect the late Professor Daniel Shapiro, who passed away in January 2025. This paper was among the final projects to which he made significant contributions. His intellectual legacy continues to inspire this work.

About the Authors

Jing Li (PhD, Indiana University) is a Professor of International Business at the Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University. She has published about forty scholarly articles in management and international business journals. Her research examines international investment strategies, emerging market multinationals, state-owned enterprises, real options theory, and the interplay of geopolitics, public policy, and firm strategy.

Daniel M. Shapiro (PhD, Cornell) was Emeritus Professor of Global Business Strategy at the Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University. Over a distinguished forty-year career, he served as an educator, researcher, and Dean. He authored five books and monographs, and more than 100 scholarly articles on international business and strategy, corporate governance, foreign investment, industrial structure, and public policy.

Carlos Vecino (PhD, HEC Montréal) is a Full Professor at Universidad Industrial de Santander (UIS). He holds a Master of Science in Finance from the University of Illinois and a degree in Industrial Engineering. He has served as a visiting professor in Finance and International Business at HEC Montréal and as an invited researcher at the Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University. He is the author of multiple academic articles and books in international business and finance.

For further theoretical development, Bucheli et al. (2023) provide a useful transaction cost economics perspective to explain how MNEs adjust global value chain activities under contractual and policy uncertainty.

We use S&P Global’s SNL Metals & Mining dataset and focus on active mines in Latin America producing critical minerals, defined by the U.S. Department of Energy’s 2023 list (https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/preprint-frn-2023-critical-materials-list.pdf).