Introduction

Botswana and Equatorial Guinea (EG) stand out among resource-rich, least-developed countries (LDCs) of Africa in that they successfully used FDI in extractive industries to spark off an economic boom and advance to the category of upper middle-income (UMI) countries. Eventually, in democratic and well governed Botswana, the boom gave way to a slower GDP growth, too slow to bring the country closer to a high-income status. Authoritarian and poorly governed EG, in turn, fell into an economic crisis and lost much of the income gains. We analyze economic experiences of both countries and argue that to restore economic vigor they need to embark on a new development model underlining commitment to economic diversification. We provide insights into actions policy makers should take. Generic insights are the same for both countries and, for that matter, any other country dependent on foreign direct investment (FDI) in natural resources. Specific insights differ because they are determined by both countries’ resource endowments and situations in five policy areas. The paper also includes insights into FDI opportunities arising out of the new economic model.

Economic and Social Performance

After World War Two Botswana and EG were very poor agricultural countries, which gained independence from, respectively, Great Britain (1966) and Spain (1968). The extraction of diamonds in Botswana since 1967 by a joint venture between a multinational enterprise (MNE), De Beers, and the government generated an economic boom, which has earned Botswana a reputation of „an African success story" (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, 2001). Between 1968 and 1991, GDP per capita grew at 9% annually, the highest rate in the world. In 1994, with GDP per capita equal to $4,219, Botswana was graduated from LDCs, and since 1997 it has been classified as an UMI country. In the last decade of the 20th century and in the 21st century its GDP per capita has continued to grow, albeit more and more slowly, respectively at 2.7% and 1.5% per year, achieving $7,236 in 2023 (chart 1). During 2001-2023 UMI countries grew more than three times faster than Botswana.[1]

The economic fate of EG changed with the discovery of oil in 1996, preceded by an earlier finding of gas. EG has attracted US MNEs to hydrocarbons’ mining and between 1997 and 2008 its GDP per capita increased at 24% annually (the rate unmatched anywhere in the world), reaching a peak of $13,048 and making an average citizen of EG the wealthiest person in Africa. After that, with the depletion of oil and gas fields, the lack of new discoveries and falling oil prices, the boom ended abruptly. Between 2009 and 2023, the GDP shrank at −6% per year, falling to $5,118 per capita, 2.5 times lower than in the peak year, and lower than in Botswana. Interestingly, the World Bank graduated EG from LDCs group only in 2017, when GDP per capita was half of the peak level, but still high enough to allow for graduation (chart 1).

Spending windfalls from natural resources, autocratic and corrupt EG has focused on large projects such as airports, highways, luxury hospitals, universities, or high-rise government buildings in both the island capital, Malabo, and the largest continental city of Bata. After this it started building in the middle of the jungle a new administrative capital, Oyala, absorbing vast amounts of money. By one estimate, some 80% of the budget was spent on large projects (IMF, 2024a; Wikle, 2019). Democratic Botswana has also improved infrastructure but paid greater attention to social spending. As a result, although EG has achieved progress on social outcomes, and on some has caught up with Botswana (e.g., on expected years of schooling), on most it lags Botswana and the differences are large.

A New Development Model

Large FDI inflows into the mining of small economies have changed their economic structure but have made them dependent on single natural resources. Botswana gets (in 2019-2023) one third of government revenue, 86% of its exports and about one fifth of GDP from diamonds. The role of hydrocarbons in EG is even larger: they account for 40% of GDP, 93% of exports, and 83% of government revenue. Over time the dependence has diminished but remains too large, especially in exports, the source of foreign currency. It signifies the lack of economic diversification and structural change needed to ensure the growth rate satisfying both countries’ aspirations.

There has been diversification towards services, the share of which in GDP has increased in EG from 25% in 2010 to 50% in 2023, and in Botswana from 32% in 1990 to 59% in 2023. But in the former, it was a statistical artifact resulting from the shrinking oil economy. In the latter, it was due to oversized, inefficient government services and low productivity activities such as trading. The share of manufacturing in GDP, a much-desired target of diversification, has declined in Botswana, from 9% in 2007 to 6% in 2023. In EG, it jumped from 7% in 2006 to 20% in 2008, and even more in later years, because of FDI by US MNEs in a large acyclic alcohols factory. But one factory has been too little to significantly boost the share of manufacturing in employment (which in the past decade has been constant around 8%) and in exports, where it fluctuated around 6%.

Thus, both countries require a new growth model, based on more productive and dynamic activities and on private sector investment, including on FDI. Future growth needs to be inclusive and anchored in new global realities such as green energy, the digital economy, shifting global value chains and financial innovation. Both countries have enough potential to invest in new sources of dynamic, diversified growth, as shown in the next section.

Recommendations for Policymakers and the Role of FDI

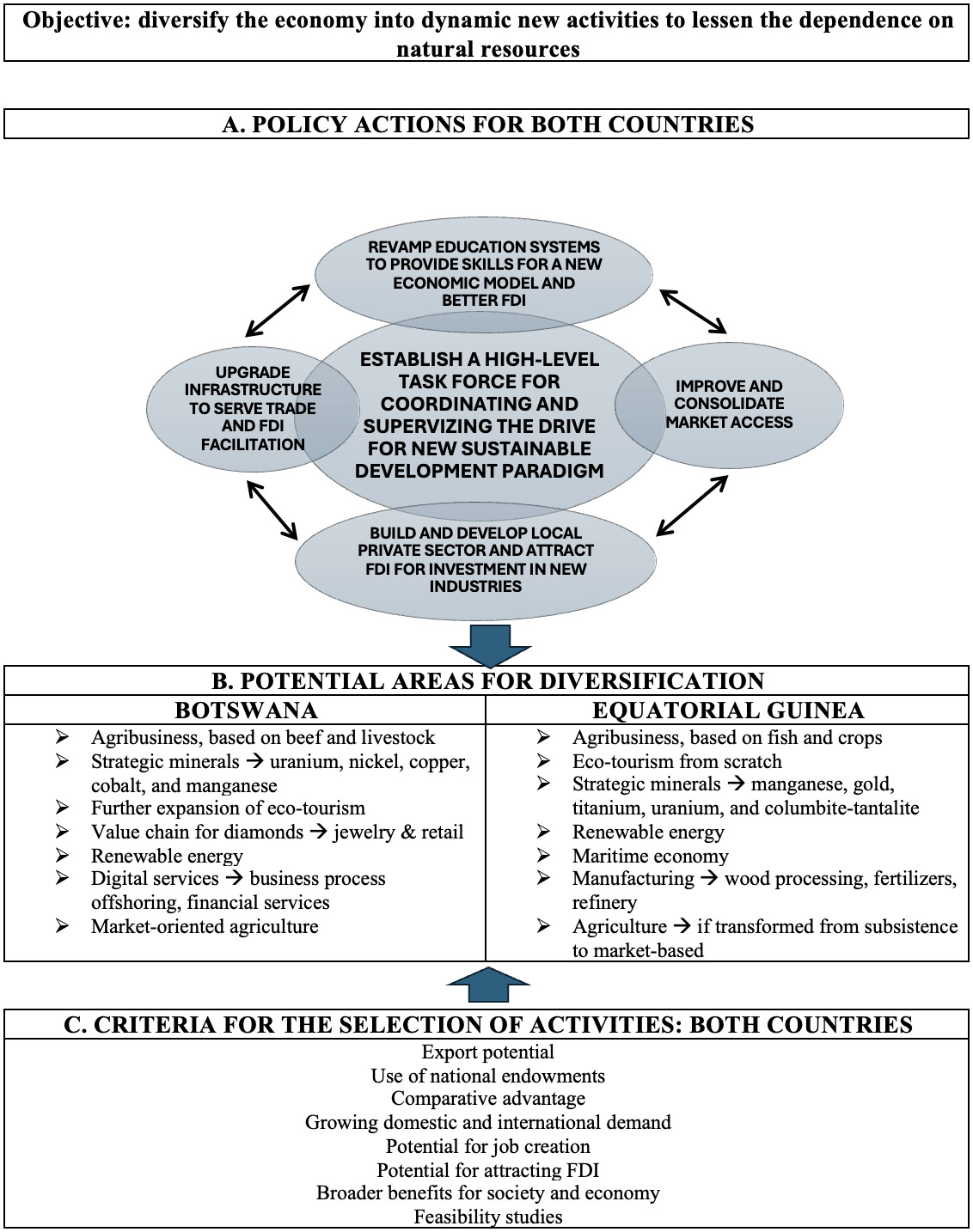

Structural change through diversification will require in both Botswana and EG similar policy actions, forming building blocks for the new economic model (table 1A). However, specific actions differ because they are determined by both countries’ resource endowments (defining areas for diversification), governance systems (democracy vs. autocracy), geographical location (land-locked vs. maritime country), institutions (e.g., advanced FDI promotion in Botswana and the lack of it in EG) and situations in five policy areas. Their implementation must be preceded by a national consensus building in democratic Botswana and an agreement on reforms among the ruling elites of EG.

Establish a High-Level Task Force for Coordinating And Supervising the Drive for New Sustainable Development Paradigm

The objective of diversification is not new in both countries. For many years it has been a part of their strategies and advice by international organizations. However, the objective has not been pursued, especially in exports, which are as dependent on natural resources as they were a decade or two ago. In authoritarian EG it should be, paradoxically, easier to achieve, as the political elite exerts total control over the country’s resources. However, it seems that actors with political clout benefiting from the status quo are not interested in initiating reforms (Bertelsmann, 2024: 31). In addition, the economic crisis has reduced financial resources.

In democratic Botswana, reforms are more difficult, as the authorities need to reckon with the voters: witness the 2024 elections, which have ousted Botswana Democratic Party after 58 years in power. Botswana has well-articulated overall and specific plans for diversification and does not lack funds to support reforms, but inadequate coordination and the lack of implementation mechanisms have limited their impact (World Bank, 2023: 29). The causes include weak accountability and monitoring, deteriorating public sector effectiveness and opposing vested interests in numerous SOEs (World Bank, 2023: xiv).

Diversification is unavoidable, if Botswana and EG wish to realize their aspirations for sustained (EG) or faster (Botswana) growth and a high-income country status. Given failures of the past, a fresh start is needed in both countries, although crisis-ridden and autocratic EG is in a much more difficult situation than Botswana. Differences aside, both need to break away from the previous ineffective institutional setup for reforms to overcome friction, opposition, and the inertia of the system. This could be done by establishing in each country a high-level task force, responsible for sustainable, green and inclusive development, reporting to the president (table 1A).

Task forces should start by reviewing past and recent programs and selecting industries for diversification as well as identifying required policy actions. This is not easy, as in each country opportunities include a dozen or so of activities, ranging from strategic minerals through offshore business services, financial centres, logistics hubs, eco-tourism or renewable energy, to the processing of gas, oil, diamonds, wood, fish, beef, etc. (table 1B). Obviously, they cannot be all pursued simultaneously. The selection, apart from identifying enabling factors such as skills or infrastructure, should consider trends in domestic and international demand and be based, for export-oriented activities, on comparative advantages and other considerations (table 1C). The key mission of task forces should be to coordinate, monitor, and supervise the efforts of various agencies responsible for developing new industries, as well as to ensure that for each industry required policy actions are in place. Cross-cutting policy actions such as infrastructure upgrading for exports of goods should be initiated and monitored by the task forces but implemented by respective agencies.

Revamp Education Systems to Provide Skills for a New Economic Model and Better FDI

The lack of skills has been identified as the key barrier to diversification and better FDI in all economic reports on both countries. Despite increased education spending, especially of Botswana (8% of GDP, compared to EG’s 2%), education systems do not produce skills required not only for a new economy but also for traditional activities. Botswana’s labor force is educated but unskilled (CDP, 2018: 23). Higher education institutions (HEIs) of Botswana produce graduates for the overgrown public sector. This is the main reason unemployment among young people is very high and inequality is one of the highest in Africa. In turn, young Guineans prefer to study arts and social sciences than to acquire digital or engineering skills. In 2020 HEIs of EG produced only seventy engineering graduates, or 12% of the total (World Bank, 2024a). The country’s petroleum industry employs few residents, while skilled jobs go mainly to expatriates (Wikle, 2019).

Thus, education systems need revamping. EG should increase education spending, which is very low for its income standard. Both countries need to change curricula at all education levels. At primary and secondary schools, attention should be given to digital skills, which are the backbone of the new economy. TVET should further develop these skills and focus on preparing skilled workers for industries chosen for diversification, e.g., for eco-tourism and renewable energy in both countries, for wood and fish processing in EG, and agribusiness of beef processing in Botswana. HEIs programs should shift towards STEM education. Both countries have taken steps to foster demand-driven higher education and vocational training. But they have not yet resulted in the level of human capital necessary for the growth activities to be promoted (ADB, 2023) and the progress achieved is not commensurate with their aspirations to become high-income economies. The unsuccessful reorganization of Botswana’s education system, reversed in 2022, resulted in a complex and fragmented organizational structure (World Bank, 2023). Pending time needed to develop local skills, both countries should lift restrictions on visas and work permits to facilitate access to regional and international skills, bridging the gap between the supply and demand.

Improve and Consolidate Market Access

EG’s exports were almost three times lower in 2023 than in 2012. Botswana’s exports do not grow. Exports continue to rely heavily on natural resources. Both countries rank at the bottom of the export complexity index: Botswana is 104th and EG 136th out of 140 countries. Both have export structure characteristic for low-income countries. Given small domestic markets, any new industry will have to be export oriented. Therefore, it is in the interest of both Botswana and EG to be the champions of trade liberalization in Africa.

Despite their smallness, both have potential for export-oriented FDI, if they remove obstacles to its attraction and ensure access to international markets. Botswana is a landlocked country, but it is strategically located in the middle of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and has access to markets with hundreds of millions of potential consumers. EG, on the other hand, has access to sea and, hence, easy access to world markets. It is also well positioned to be a major logistics and shipping hub for the neighboring region. Bata is one of the largest ports in West Africa. Thus, the country can potentially become an entry point for goods destined for two hundred million consumers in the Central Africa’s region (IMF, 2024b).

Both countries do not take full advantage of the membership of regional integration agreements such as ECCAS and CEMAC (EG) and SADC and SACU (Botswana). Within ECCAS for example, EG has the lowest scores for productive integration and the free movement of people due to restrictions on visas and residence permits (ADB, 2023). This severely limits, among others, tourism. Botswana’s trade policy within SACU strongly disincentivizes exports (WB, 2023). It, for example, protects food products, resulting in higher prices for consumers. Both countries should work to remove the remaining regional tariff and nontariff trade barriers as well as red tape at the borders, which raise the cost of intermediate inputs, reducing the competitiveness of local firms and motivating them to sell goods in small domestic markets rather than export. They should exploit the potential for integrating local value chains into regional ones, offered by the new African Continental Free Trade Area. Botswana should take advantage of joining global value chains by benefitting from the long-existing Africa Growth and Opportunity Act. EG should join the World Trade Organization to consolidate access to world markets.

Upgrade Infrastructure to Serve Trade and FDI Facilitation

The oil and diamond windfall has enabled both countries to thoroughly modernize their infrastructure, more so in EG than in Botswana, which devoted more attention to social expenditures.

EG, the territory of which consists of islands and the mainland, does not have railroads but has a modern road network, which faces maintenance issues caused by the economic crisis. Its road connections with neighboring countries remain weak. Seaports and airports are the key channels for the international movement of people and goods. Their efficiency has improved owing to the conclusion of management contracts in view of their privatization, which would be a step towards transforming EG into a maritime hub for regional transport of goods and passengers. Partnerships with the private sector could help solve infrastructure maintenance problems.

Botswana’s ground transport infrastructure is directed towards South Africa. The government has taken initiatives for diversifying transport connections, inviting foreign investors to use build-operate-transfer models. Opening of the Kanzungula Bridge over the Zambezi River in 2021, connecting Botswana with Zambia, has created a new channel for the diversification of goods trade. Adding a planned railway track across the bridge will link Botswana railways with Mosetse–Kazungula–Livingstone Railway, lower transport cost and facilitate trade between the two countries and within SADC. Another project planned to be launched in 2025, the Trans-Kalahari Railway, connecting Botswana with Namibian ports would offer an additional alternative to the South African corridor. Implementing these projects, Botswana would go a long way towards facilitating its trade with the region. Reforming the aviation industry and developing regional networks in partnership with the private sector would open new opportunities for tourism development.

Both countries have great potential for reliable, cost-effective, comparative-advantage based renewable energy generation and exports. While EG started to use it, Botswana is far behind. In the former, renewable energy accounts for a quarter of the total. In the latter almost all energy is generated by coal. EG, with the completion of the Sendje Hydroelectric Power Plant, expected in 2025, will achieve energy independence. It began to export energy by connecting its power grid with that of Gabon in 2023. Botswana has faced electricity crises and occasionally had to rely on imports from South Africa and the Southern African Power Pool for more than 90 percent of its electricity needs (World Bank, 2023). The planned BOSA transmission line to South Africa (World Bank, 2024b) would improve connectivity, but to use it for exports, Botswana needs first to invest in renewable energy. Both countries should improve a relatively low access of their populations to electricity (76% in Botswana and 67% in EG in 2022, compared to almost 100% in UMI countries), increase power supply reliability and build transmission lines to neighbors.

As regards ICT infrastructure, internet penetration rate has increased sharply in both countries in the past decade, to reach in 2022 77% of the population in Botswana and 67% in EG, compared to 80% in UMICs. However, on a more complex Mobile Connectivity Index, EG scored only 36 (out of 100) in 2023, and Botswana 60 (Mobile Connectivity Index). The overall index hides weaknesses of Botswana’s infrastructure, including low mobile broadband subscriptions (49%), poor quality of connections, often allowing to use only basic applications, and stagnating Internet speed for the past decade (World Bank, 2023). In EG, with a low overall index, the situation is even worse. Thus, to accelerate the adoption of digital technology, which is the backbone of modern business and financial services, both countries need to invest in ICT infrastructure.

In both countries the cost of internet access and digital services is very high and the level of digitization of government services low. The underlying cause is the high government participation in the provision of infrastructure and services, although the situation differs between the two countries. Botswana has a relatively progressive policy and regulatory framework, which allowed the entry of foreign firms, including Orange and Mascom Wireless, into the mobile broadband digital market, which they share with the state-owned enterprise (SOE), Botswana Telecommunication Company (BTC). The market is considered highly concentrated and non-competitive (World Bank, 2022). In addition, the broadband wholesale and fixed retail markets are dominated by BTC (which sells services to retail providers and competes with them at the same time) and another SOE, BoFiNet. As a result, the price and quality of wholesale broadband services are considered a key barrier to Botswana’s digital transformation. Therefore, the World Bank advocates the introduction of competition to the wholesale market through allowing additional players or selling a stake in BoFiNet to a private strategic [foreign] partner (ibid.). In EG, mobile services are provided by a joint venture between the government and Chinese ZTE telecom equipment manufacturer, and local business groups (World Bank, 2024a). The country has yet to establish an independent regulator.

Following the examples of almost all other African countries, where both the traditional and new operators of mobile licenses are MNEs such as Airtel, MTN, Orange, Maroc Telecom, Etisalat or Viettel (World Bank, 2024a: 48), Botswana’s and EG’s governments would be well advised to withdraw from the provision of services, leave them to private domestic and foreign firms, establish (EG) and strengthen (Botswana) independent regulators supported by competition laws with all necessary power to regulate the market efficiently. EG should consider attracting a Spanish MNE, Telefónica. Both should also implement a long-waiting intention to privatize energy SOEs to foreign investors, and obligate them to invest in renewable energy, especially in Botswana. They should provide energy subsidies to poor households only.

Build and Develop Local Private Sector and Attract FDI for Investment in New Industries

The local private sector, a candidate for investment in the new economy, needs to be built from scratch in EG and developed in Botswana. In EG it consists nearly entirely of small informal services firms operating mainly in urban areas. There are almost no local private firms in industries with high-growth potential, such as fisheries, agribusiness, agroforestry, construction, transport, logistics and tourism (ADB, 2023: 8). In Botswana, the sector is more visible but most local firms are oriented towards the domestic market, providing non-tradable services and often dependent on government contracts. There are several local firms in diamond cutting and polishing, but they are rather an exception to the general weakness of the private sector, which is commonly considered as the main cause of the recent sluggish growth and the lack of job creation (ADB, 2023; IFC, 2022; World Bank, 2023).

Pending the emergence of dynamic local firms, both countries will have to rely on FDI for new activities needed for diversification. So far, they have attracted little FDI beyond natural resources. In Botswana, foreign firms are present in financial services, tourism, and trading. EG, as mentioned earlier, has a large US-owned chemical plant. Besides, there are foreign firms in fuel distribution and construction. EG faces an immediate problem of replacing Exon-Mobil, which discovered oil in the country but withdrew in 2022, when its license expired. To facilitate replacement, in 2024 the government reduced corporate income tax from 35% to 25% and the tax on dividends from 25% to 10%.

Botswana should have it easier to attract FDI into non-diamond activities because its investment climate is much better than that in EG, as manifested by a much higher position on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business: in 2020 Botswana ranked 87th and EG 178th. The government actively promotes FDI and offers incentives such as tax breaks and streamlined regulatory processes. It has set up Botswana Investment and Trade Centre (BITC), which serves as a one-stop shop, simplifying the investment process and promoting Botswana as an investment hub. The Centre also plays a role in the development of special economic zones, set up to attract FDI. Botswana should remove or revise legislation, which discourages FDI such as the Public Procurement Act of 2021 or the 2022 Economic Inclusion Law (World Bank, 2023: 30).

The government of EG, in collaboration with the World Bank, embarked on a comprehensive reform aimed at enhancing its investment climate, revitalizing the business environment, and attracting both domestic and foreign investment.[2] First steps included the establishment of a one-stop shop for starting a business and reducing the minimum capital requirement. EG will have to address several hurdles in the investment climate, including government efficiency, the quality of regulations and the rule of law. The country should finalize access to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and establish an Investment Promotion Agency.

Estimates are that in EG the ten-year average annual growth potential is enormous and amounts to 18% in industrial fishing, 16% in maritime transport, 15% in electricity and 12% in agriculture, if it is transformed from subsistence into market activities (ADB, 2023). Similar estimates exist also for Botswana.

Botswana and EG are small countries, which are not on MNEs’ radar for FDI in export-oriented manufacturing and services industries. But examples of countries such as Costa Rica and the Philippines indicate that even small countries can achieve excellence in FDI promotion. Costa Rica reformed technical education and regulations, changed incentives and upgraded infrastructure to attract an anchor investment by Intel, which led to additional foreign and domestic investments in electronics and medical equipment. The Philippines has become a global hub for BPO and is the second largest provider of business services after India (World Bank, 2024b).

Conclusion

Launching and implementation of the new economic model will take time. Meanwhile both countries will have to rely on diamonds and hydrocarbons for financing reform and acquiring foreign currency. But diversification is indispensable if they wish to regain economic momentum. The sooner they take steps to initiate it, including through FDI attraction into new activities, the quicker the chances to break away with the old stagnant or crisis-prone system. Although policy actions they need to take are similar in general (but different in details), crisis-ridden, and autocratic EG will have it harder than democratic and quite well governed Botswana.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Editors for their useful and friendly guidance as well as the three anonymous reviewers for comments.

About the Author

Zbigniew Zimny is Professor of International Economics at Vistula University in Warsaw. He worked for 20 years for the United Nations in New York and Geneva, managing and doing research on MNEs and development. He was Head of the UNCTAD’s branch publishing World Investment Reports and led the teams preparing Investment Policy Reviews of African countries such as Botswana, Lesotho, and Tanzania. He has written extensively for the United Nations and academia on FDI and development, globalization, regional economic integration, and international business policy.

GDP growth data in this and next paragraphs are author’s calculations based on World Bank’s data: GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$) | Data.

Equatorial Guinea’s Investment Climate Reforms: Facilitating Growth Amid Economic Transition