Introduction

The Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between India and the United Kingdom (UK) represents a key development in the changing landscape of globalisation, particularly amid shifting geopolitical dynamics and the rise of bilateral trade agreements. As India’s first comprehensive trade agreement with a major European partner and Britain’s most significant post-Brexit trade initiative, the FTA is strategically and symbolically important. In the broader context of globalisation, the FTA exemplifies the shifting dynamics of international trade where bilateral agreements are increasingly utilised to foster economic integration and mutual growth (van Bergeijk, 2019). The UK’s pursuit of this agreement aligns with its ‘Global Britain’ strategy, seeking to establish stronger ties with emerging markets. India, with its rapidly growing economy and expanding middle class, presents a significant opportunity for the UK to diversify its trade partnerships and reduce reliance on traditional markets. Nevertheless, the FTA introduces a distinct set of challenges for the broader South Asian region. A critical question that emerges is will the FTA, beyond serving the interests of its two signatories, contribute to regional integration or induce trade diversion that would undermine South Asia’s collective economic cohesion?

This paper examines the India–UK FTA’s dual role as both a driver of cross-border supply-chain integration and a source of trade diversion, contributing to the debate on how emerging economies use trade diplomacy to shape economic governance. Unlike much literature focusing on the limitations of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA), this analysis considers the strategic impact of India’s shift towards bilateral agreements with advanced economies, arguing that such moves may widen regional disparities and undermine South Asian multilateralism. Rather than emphasising post-colonial narratives, the paper contends that India’s deepening integration into Western economic networks generates both opportunities and challenges for regional cohesion. From this perspective, the India–UK FTA is not simply a milestone in bilateral relations; it also compels a re-examination of the institutional architectures that shape South Asian trade, highlighting the importance of balancing hard connectivity with soft institutional frameworks to support inclusive growth. In doing so, the paper both draws on and challenges existing policy discourse by calling for a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between bilateralism and regionalism in shaping economic outcomes across South Asia.

FTAs and the Rise of India as a Global Economic Power

India’s ascent as a global economic power has positioned it at the centre of international trade diplomacy, with FTAs serving as a principal instrument of this transformation. As the world’s most populous nation and the fifth-largest economy by nominal GDP, India’s influence in global commerce has grown markedly, with FTAs underpinning much of this progress.

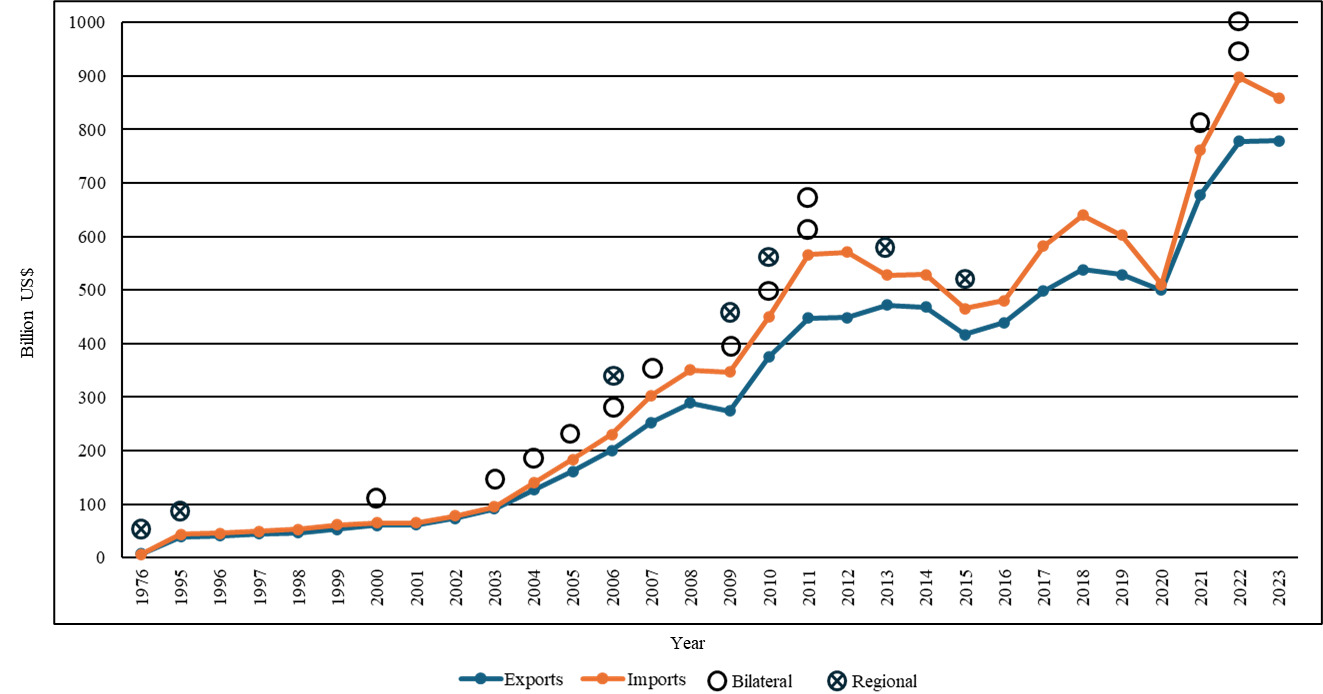

As shown in Table 1, India has concluded 13 bilateral and 5 regional trade agreements, in addition to the FTA with the UK, over the past four decades, with negotiations currently underway for additional four regional pacts. This surge in trade agreements underscores India’s strategic intent to integrate deeply into the global economy. Majority of these agreements have been established with neighbouring South Asian countries, reinforcing India’s stature as a regional leader and its commitment to regional development. The FTAs have delivered clear benefits for India, as confirmed by Figure 1, which illustrates sustained growth in trade flows following their implementation.

India’s largest trading partners continue to include the United States, China, and the United Arab Emirates, each accounting for a substantial share of India’s total trade volume. However, Britain’s importance is amplified by its status as India’s leading trade partner in Europe. Since the early 1990s, bilateral trade between the two nations has expanded significantly, exceeding US$15 billion by early 2010s, fuelled by British demand for Indian products such as pharmaceuticals, textiles, and information technology (IT) services (Raiser & Ohnsorge, 2025). By 2024, the total value of goods and services traded reached approximately US$55 billion, with the UK recording a trade deficit of US$11.5 billion (Department for Business & Trade, 2025). This upward trajectory persisted into 2025, as India’s exports to the UK grew by 8.4% year-on-year in March (Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2025), highlighting Britain’s rising importance as a strategic trade partner for India.

The India–UK FTA reflects a broader shift in global trade, with the UK viewing India as a crucial partner post-Brexit, and India seeking to diversify trade beyond its traditional Asian ties. This mirrors a global trend where emerging economies increasingly favour bilateral over multilateral agreements. Geopolitically, the FTA strengthens India’s strategic position by reducing dependence on China-centred supply chains and enhancing its appeal to Western economies. The agreement also bolsters India’s reputation as a rules-based, investment-friendly economy, especially in digital trade, clean energy, and pharmaceuticals, encouraging foreign investment and technology transfer.

Bilateral FTAs have yielded more targeted benefits for India than regional agreements. For instance, the India–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), signed in 2011, eliminated tariffs on roughly 90% of traded goods and has facilitated export growth in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and textiles, with tariffs further reduced to 94% over an eleven-year period with notable tariff reductions on farm, forest, and marine products (Embassy of Japan in India, 2025). Similarly, the India–UAE CEPA has enhanced market access to Indian pharmaceutical firms by streamlining regulatory approvals for generic medicines, while the agreement with Korea has leveraged India’s comparative advantages in digital and engineering sectors. By contrast, regional trade agreements, such as SAFTA, have delivered modest outcomes, reflecting the persistence of high trade costs, regulatory barriers, and uneven levels of development. It is, therefore, strategically prudent for India to focus on bilateral agreements with advanced economies, which offer more opportunities for technology transfer and innovation-led growth (Krammer, 2015).

What Does the FTA Mean for South Asia?

The India–UK FTA holds significant implications for South Asia, exposing the region’s diverse approaches to trade agreements. While all eight South Asian countries are signatories to the SAFTA, their engagement with bilateral FTAs varies, reflecting differing economic and political priorities. As shown in Table 2, India has bilateral FTAs with most neighbours except Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Maldives – gaps largely attributable to political tensions or trade volume.

The India–UK FTA exemplifies a ‘hub-and-spoke’ dynamic, granting Indian firms extensive tariff-free access to the UK, which could divert preferential trade away from other South Asian economies still subject to SAFTA tariffs. This risks eroding the market share and incentives for regional cooperation among smaller countries, thereby undermining SAFTA’s multilateral integration goals. India’s ongoing focus on external bilateral agreements, such as the proposed India–EU FTA, may further marginalise regional partners and dilute SAFTA’s institutional effectiveness, entrenching India’s role as a regional hub at the expense of broader South Asian cooperation.

Can the FTA Usher Opportunities for Regional Growth in South Asia?

The India–UK FTA offers strong prospects for regional development in South Asia. By boosting Indian exports to the UK, it drives demand for intermediary goods, particularly as major Indian firms expand production hubs in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The opening of Colombo West International Terminal by the Adani Group further enhances intra-regional connectivity. These advancements mean that tariff reductions will not only strengthen India–UK trade but also encourage South Asian countries to use Indian infrastructure, deepening their integration into regional value chains.

The FTA enables India to spread trade benefits across South Asia by leveraging its logistics hubs and improving regional supply chains. For example, Nepal’s new Dodhara Chandani dry port, linked to India’s Jawaharlal Nehru Port, will reduce reliance on congested Kolkata port and cut transit costs, boosting Nepalese exports like textiles and handicrafts (SASEC, 2025). India’s shipping deal with Bangladesh also allows direct maritime freight to Mumbai, bypassing Colombo, which enhances competitiveness for Bangladesh’s garment sector. Reflecting these enhanced trade linkages, Bangladesh’s garment exports reached US $38.5 billion in 2024, with almost US $4 billion destined for the UK (Trading Economics, 2025). These advances also help British retailers lower sourcing costs and deepen supply chain ties with South Asian partners.

India’s strategic ambition to become a regional logistics and digital services hub aligns with Britain’s interests in building more resilient and diversified supply chains (Government of India, 2025; Government of UK, 2025). Moreover, increased market access for Indian goods and services may have positive spillovers for neighbouring economies through demand for intermediate goods, technology diffusion, and labour mobility. For countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, the FTA thus presents opportunities not just for indirect gains, but for proactive participation in global supply chains anchored by Indian firms targeting Western markets.

As Lee (2014) notes, FTAs aim to lower trade costs by improving supply chain integration—an objective closely matched by the India–UK FTA. Growth in trade often increases regional industrial productivity (Kleinert, 2003). The FTA could benefit neighbouring South Asian economies if paired with targeted infrastructure investments and streamlined logistics, especially for landlocked countries like Bhutan and Nepal. Enhanced transport corridors and logistics hubs would help move Bhutanese and Nepali handicrafts through Indian ports to British markets. This positions the India–UK FTA as a catalyst for wider South Asian economic cooperation, with its benefits reaching beyond mere trade volume and supply chain integration.

Risks and Potential Adverse Impacts of the FTA

Despite its unparalleled benefits, the FTA comes with caveats. Trade diversion remains a major threat. In the context of South Asia, Indian exports often dominate due to lower production costs, potentially displacing third-country imports and reducing welfare gains for its neighbours. Bangladesh in particular, which is a major manufacturing hub for leading Western firms, may incur net welfare losses due to significant trade diversion. In relation to its textile exports to the UK, Bangladesh is estimated to incur a loss of approximately $50 million due to trade diversion representing 12.5% of its total textile export value of $4 billion in 2024 (BGMEA, 2025).

The risk of trade diversion is further exacerbated by high trade and transport costs across South Asia, driven by inadequate infrastructure, inefficient customs procedures, and congested land border crossings. For landlocked countries such as Nepal and Bhutan, the situation is even more critical due to their reliance on transit through India. Without complementary measures such as regional infrastructure investment, streamlined border management, and parallel trade agreements for neighbouring states, the India–UK FTA could deepen asymmetries in regional trade, undermining the goal of inclusive economic integration in South Asia.

The FTA also poses challenges for South Asian regionalism. India’s pivot towards bilateralism, exemplified by this FTA, may undermine collective efforts such as the SAFTA, which has struggled due to political and structural constraints. The asymmetry in India’s trade capabilities and its focus on external partnerships might widen economic disparities within the region unless smaller nations proactively align their trade strategies.

Critics highlight that the India–UK FTA would allow approximately 85% of British exports to enter India duty-free, potentially saturating local markets in a manner reminiscent of colonial-era trade dynamics. Additionally, the introduction of UK carbon tariffs in 2027 poses a significant threat to approximately $775 million worth of Indian exports, especially impacting carbon-intensive industries such as steel, aluminium, and cement, thereby exacerbating competitive pressures and market vulnerabilities for Indian producers (Mishra, 2025).

Practical and Policy Implications

The India–UK FTA holds significant potential for driving economic growth and deepening regional integration across South Asia. Yet, its effects on neighbouring economies are inherently complex – simultaneously ostering integration for some countries while risking exclusion for others. To help policymakers and trade professionals systematically assess these differentiated outcomes, Table 3 presents a typology outlining the principal pathways through which the FTA can produce both integrative and exclusionary effects across the region. This framework serves as the analytical foundation for the subsequent implications for both managers and policy makers, which translates these insights into concrete actionable strategies.

Trade Diversion

To address the risk of trade diversion, a combined approach of hard infrastructure investment and soft policy reforms is essential. The development of cross-border transport corridors such as the Bangladesh–Bhutan–India–Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement and the South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) should be aligned with more liberalised trade regimes. These initiatives aim to connect Bhutan, Nepal, and Northeast India with deep-sea ports, lowering transit costs and expanding market access for less-industrialised neighbours. Integrating such physical connectivity with regional FTAs can help offset trade-diversion risks, enabling smaller economies to diversify trade with wider blocs like Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) or through bilateral pacts with Japan, Korea, the European Union, and the United States, thus avoiding ‘hub-and-spoke’ dependencies (World Bank, 2025).

Supply Chain Integration

To deepen regional supply chain integration, South Asian manufacturing hubs such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka should pursue bilateral agreements with major trading partners, mirroring Pakistan’s experience with its FTA with China, which successfully embedded its industries in global value chains. For Bangladesh, a dual approach – negotiating an FTA with India or the UK, or fostering a trilateral agreement with both – would align with its ‘Perspective Plan 2041’ to become an export-driven, upper-middle-income economy. Such strategies would enhance linkages within regional production networks and sustain competitiveness in key sectors like textiles, which remain vulnerable to changing tariff regimes.

Policy and Regulatory Realignment

Despite strong economic ties, India and Bangladesh lack an FTA, even as their bilateral trade reached around US$14 billion in 2023–24, with a notable imbalance favouring India. A formal agreement could mitigate trade diversion by reducing non-tariff barriers, streamlining customs, and encouraging cooperation in textiles, pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and energy. This would lower transaction costs, diversify exports, and foster deeper regional integration. Coordinated infrastructure investment, supported by the World Trade Organisation’s Aid-for-Trade and inclusive regional trade arrangements, offers the most credible path to neutralising diversionary effects and distributing welfare gains across South Asia.

Infrastructure Asymmetry

In the longer run, embedding the India–UK FTA within a broader regional integration strategy by fast-tracking connectivity projects, upgrading infrastructure, and expanding port and inland hub capacity will lower logistics costs and enhance competitiveness across South Asia. Addressing infrastructure asymmetry is particularly critical to prevent the exclusion of landlocked economies such as Nepal and Bhutan. Coordinated infrastructure planning, development of trade corridors, and investment in dry ports and inland logistics hubs will help distribute the benefits of regional trade more evenly. Leveraging Aid-for-Trade mechanisms and regional connectivity initiatives can further neutralise diversionary effects, foster inclusive growth, and ensure that businesses and policymakers alike maximise the FTA’s potential while mitigating its structural risks. Moreover, regional firms are encouraged to invest in local capabilities and promote technology transfer, ensuring South Asian economies can maximise the benefits of the India–UK FTA while mitigating its risks.

Spillover and Competition Effects

Given the evolving trade landscape, firms are increasingly compelled to reassess their production networks in response to shifting tariff preferences and market access opportunities under bilateral FTAs such as the India–UK agreement. In particular, Bangladeshi multinationals must adapt supply chains to leverage India’s tariff concessions by either deepening production partnerships in neighbouring countries or diversifying to hedge against the risk of trade diversion. Although estimates project that Bangladesh’s apparel exports to the UK may shrink by about US$50 million after the FTA, these adverse effects could be offset by timely ratification of regional frameworks like the Bangladesh–Bhutan–India–Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement, which could boost intra-regional trade by nearly 60% (World Bank, 2023). Policymakers should prioritise customs modernisation, logistics upgrades, and cross-border transport improvements to enhance trade facilitation and keep Bangladesh competitive within shifting regional value chains.

Conclusions

The India–UK FTA signifies a shift from multilateral to bilateral trade, marking Britain’s eastward economic focus and elevating India’s role in a multipolar world. While India secures strategic gains through its large market and skilled workforce, concerns arise over regional disparities and the marginalisation of neighbouring South Asian economies. To address diversion risks and capitalise on new FTAs, policymakers should prioritise infrastructure and regional integration, while also aligning national trade strategies with broader regional integration to enable smaller economies to benefit from new FTAs. At the same time, multinationals must adapt their supply chains to maximise tariff concessions and maintain competitiveness in evolving trade dynamics. To summarise, the India–UK FTA offers significant promise for economic development, but its implications for South Asia hinge on how regional actors respond to the evolving trade architecture.

Acknowledgements

Dr Pratik Arte would like to thank the Editor, Professor William Newburry, and two anonymous reviewers, whose insightful feedback and thoughtful observations were invaluable in shaping this article into its present form.

About the Author

Dr Pratik Arte is India Research Fellow at the Stockholm School of Economics and Associate Research Fellow at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs. His research focuses on globalisation, trade and investment, and labour migration. Previously, Pratik has held academic positions at Brunel University of London, Northumbria University, and University of Vaasa. He is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a Chartered Management and Business Educator.