BIG Question

What drives firms to choose different nonmarket strategies?

Introduction

Managers are more and more challenged in the way they run their firms, as economic and geopolitical tensions have increased, and nationalistic forces have been on the rise. Besides governments and other types of nonmarket actors like non-governmental organizations, industry and consumer associations as well as grassroots movements (e.g., Fridaysforfuture) increasingly target firms and fuel discussions regarding regulation, e.g., self-regulation and private politics. Managers find themselves in the center of these discussions as their firms face institutional contexts that are generally characterized by ever-increasing complexity. When facing the liability of foreignness, as well as continued differences in host- and home-country conditions, various institutional dimensions continue to have considerable consequences for multinational enterprise (MNE) subsidiaries’ incentives to engage with nonmarket actors through the use nonmarket strategies (NMSs), in particular. My dissertation research aimed to better understand the incentives and drivers behind firms’ NMSs.

Nonmarket Strategy: What Is It and Why Should We Care?

The term NMS has been used to describe different approaches and firm behavior vis-à-vis nonmarket stakeholders, such as governments and social actors. With the increasing importance of the nonmarket and nonmarket influences in our contemporary world, NMS as a field has received considerable scholarly attention following Baron’s (1995) seminal work. Research has emphasized the impact of institutions on firms’ NMSs (for a recent integrative review of NMSs, see, e.g., Dorobantu, Kaul, & Zelner, 2017). It has shown that NMSs help firms cope with institutional and political hazards, obtain country knowledge, achieve legitimacy, and ultimately attain competitive advantage. Previous research suggests that firms carefully consider which type of NMS to use and that the choice depends on firm-, as well as on institutional- and country-level factors (Doh, Lawton, & Rajwani, 2012).

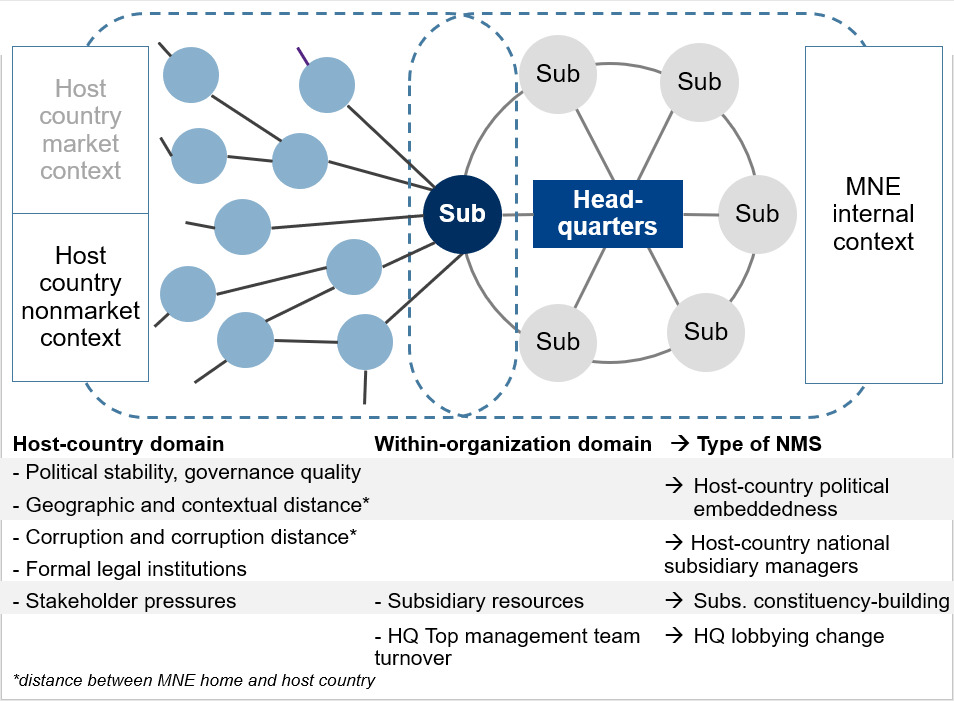

My research zooms in on different country-level/institutional, but also firm-level/managerial conditions and how these may influence firms’ nonmarket strategic decisions. I assume that institutions have an influence on firms’ NMSs and acknowledge the influence of differences between home- and host-country institutions in the context of MNEs. Moreover, I highlight the potential impact of firm-level factors in terms of resources and stakeholder pressures and top management team (TMT) turnover. These factors are depicted in Figure 1, which illustrates the drivers I have focused on in my study of NMS.

My research informs the literature on drivers of NMSs. First, it contributes to research suggesting that the value of NMSs differs across countries. By emphasizing the impact of fine-grained institutional country characteristics, I challenge the assumption that institutions in a broad sense influence MNE subsidiaries’ NMS decisions. Instead, very specific types of institutions and their respective qualities are likely to have an impact on the choice and intensity of NMSs. Second, by theorizing about NMS changes and the impact of TMT turnover on such changes, I advance recent literature that suggests looking at other dimensions of NMSs than total expenditures or intensity. I also offer important insights for NMS research by highlighting the role of changes in NMSs and providing a novel explanation for differences in firms’ NMSs that builds on firm-level factors, namely TMT turnover.

How “Space” and “Place” Influence Subsidiary Host-Country Political Embeddedness

When subsidiaries engage with their host country political context, does it matter how geographically and contextually distant they are from their headquarters? And what role does the host-country context of the subsidiary play, when it comes to determining the extent of subsidiary host-country political embeddedness? It is critical for MNEs to strike a balance between high subsidiary host-county political embeddedness that requires attention and is resource-intense, and low embeddedness that may mean that a subsidiary misses out on the insights and benefits that political embeddedness can bring.

As a part of MNEs, subsidiaries operate in host countries that differ from the MNE home country and have to deal with actors in this host-country context. Host-country political embeddedness in particular, helps subsidiaries to obtain knowledge and understanding of the regulatory and political context, and to get access to local networks. While subsidiaries also get some guidance and support from their headquarters, the distance between MNE home and host countries may alienate subsidiaries from the MNE. This distance may thus influence the extent of subsidiary host-country political embeddedness.

I tested the relationship between distance, host-country context, and subsidiary political embeddedness using a sample of 124 European manufacturing subsidiaries and found that distance (space) between MNE headquarters and subsidiaries and host-county context (place) matter jointly for subsidiaries host-country political embeddedness. My results suggest that subsidiary host-country political embeddedness is not equally spread across MNE-subsidiary dyads and it also appears to depend on the host-country context where a subsidiary finds itself in. Subsidiary managers can choose how strongly they become embedded in their host-country political context. In making their choice, they can consider factors related to headquarters support, as well as the specific host-country political and regulatory context.

Trojan Horses or Local Allies: Host-Country National Managers in Developing Market Subsidiaries

MNEs can draw on host-country national (HCN) managers to capitalize on their knowledge and understanding of the host-country context. Besides market knowledge, HCNs can also bring important nonmarket knowledge that matters for MNEs to successfully operate across countries. I investigated under which host-country conditions MNEs draw on HNCs – and to what extent.

I theorize that formal legal institutions protect foreign MNEs from potential costs that may be related with HCNs, encourage the use of HCNs and reinforce their potential benefits. Corruption as an informal institution and corruption distance however, increase perceived costs associated with HCN managers up to a point at which they outweigh their perceived benefits. This suggests that HCN managers may be commonly associated with specialized knowledge, superior responsiveness, and legitimacy. Yet HCNs’ local familiarity may also be perceived as risky by MNEs, which may limit their use of HCNs.

Analyzing how formal and informal institutions affect the trade-off between potential positive effects and costs associated with HCN managers (“Local allies” vs. “Trojan horses”) in a unique dataset covering 4,029 developing-market MNE subsidiaries, I found that legal institutions protect foreign MNEs from potential costs, encourage the use of HCNs and reinforce their benefits. Corruption and corruption distance however, increase perceived costs associated with HCN managers up to a point at which they outweigh their perceived benefits. My research suggests that practicing managers are aware and consider the potential upside and downside risks related to subsidiary managers’ nationality.

Nonmarket Strategies in Different Institutional Contexts: Disentangling the Effect of MNE Subsidiary Resources on Constituency Building

Are more resourceful subsidiaries investing more into constituency-building strategies or do their resources enable them to resist nonmarket influences? In answering this question, I shed light on the drivers of constituency-building by theorizing about the twofold effect of resources on constituency-building as a NMS. I thereby expand the largely demand-driven perspective on NMS, which suggests that firms engage in NMS as a reaction to external pressures. Thus, I argue that subsidiaries’ resources need to be considered to get a more complete picture.

Investigating my theory on a sample of 151 developing-market MNE subsidiaries, my results indicate that, on average, more resourceful subsidiaries use more constituency-building strategies. However, the effect of subsidiary resources depends on the institutional context in terms of stakeholder pressures in the host country: More resources also enable the subsidiary to resist stakeholder pressures. These results contribute to research on the contingencies of NMSs in particular, constituency-building strategies, as well as the role of subsidiary resources in different institutional contexts. My results suggest that subsidiary managers consider the availability of resources, as well as the presence of stakeholder pressures as distinct factors, when they decide about the extent to which they engage in NMS.

Top Management Team Turnover and Corporate Political Activity Change

When firms invest in NMS, what determines if they are later willing or able to change their NMS or not? Practitioners have increasingly sensed that political changes affect firm strategy (e.g., McKinsey & Company, 2016, 2019). But how about managerial factors? I address a theoretical puzzle regarding the link between TMT and lobbying changes.

I distinguish between two types of TMT turnover, one concerning turnover among a TMT in general and one concerning turnover among politically-connected TMT members. I argued that turnover among politically-connected TMT members, in particular, affects changes in lobbying. The argument is that politically-connected TMT members have political networks, insights and interests, which make them more focused on decision-making on NMS. If there is a turnover among politically-connected TMT members, they will likely be more willing or able to engage in discussions about NMS changes and initiate actual NMS changes, such as changes in lobbying.

I tested my theory and my results indicated that political but not general TMT turnover facilitates lobbying change. More generally, my results suggested that managers with a political background are likely to have a different agenda as part of a TMT and work on different parts of strategy than non-politically-connected TMT members.

Contributions and Implications for Practitioners

My research tries to emphasize both potential benefits and costs related to NMSs in different institutional contexts. While my dissertation does not give an answer as to “if” and “when” NMSs and changes therein are beneficial or detrimental to firms, it indicates that not all firms are equally capable and willing to employ or change their NMSs. Indeed, my research on NMSs in different institutional contexts seems to suggest that the use of NMSs is a matter of adaptability. By also looking at NMSs over time, my research evokes practitioners to reflect about their own firm’s ability and willingness to change NMS.

My dissertation research carries a primary managerial implication, namely that in order to capitalize on NMS and knowledge benefits that might incur from it, firms may try to anticipate institutional loopholes for and safeguards against opportunistic or detrimental behavior of nonmarket actors (McKinsey & Company, 2016). My research suggests that the incentive to use NMSs is particularly high for MNEs and their subsidiaries, because foreign MNEs might be treated less favorable than domestic firms in a host country. Even if they are not treated unfavorably on purpose, MNE subsidiaries as well as headquarters can use NMSs to compensate for their lack of host-country knowledge and understanding. For their NMS to potentially pay off, however, they may pay attention to the institutional specifics of the nonmarket context.

My research also informs practitioners’ insights into the role of NMS – as a potential complement to market strategy. While practitioners take particular note of the rapidly changing socio-political conditions and the challenges they bring for their market strategy (McKinsey & Company, 2019), my dissertation points to the increasing relevance for practitioners to get savvy in the options they have to interact with nonmarket actors. My research suggests that it is particularly acute for managers to understand what types of NMS may be more appropriate and prevalent when acting with and reacting to nonmarket actors, but also what changing conditions may imply for NMS and changes thereof.

About the Author

Patricia Klopf (klopf@rsm.nl) is an assistant professor of Strategic Management at the Department of Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship at Rotterdam School of Management. She received her PhD in Global Strategy and an MSc in Economics from Vienna University of Economics and Business. Patricia is interested in nonmarket strategy and institutional drivers of firm strategy: She is particularly fascinated by how firms access and manage their political context through nonmarket strategies in the context of complex and dynamic institutions.