Why Leaders Should Care about Reputation

This article provides insights for leaders on managing multiple and conflicting reputations within a global context. Imagine the challenges a CEO of a US technology firm might face trying to attract foreign talent from China with ongoing tensions between the US and China. Or imagine the difficulties the Minister responsible for the Department for International trade in the UK might be confronting with striking trade agreements with non-European Union states during the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union (Brexit). These are just two of many examples of where business and political leaders can face major operational challenges owing to the multiple and conflicting reputations of their business and political entities. Although reputations can be shaped by activities and events that are often outside of the control of leaders, they nevertheless require careful management.

Defining Reputation

It is generally agreed that reputation is a collective evaluation of an entity (e.g., country, organization, team or individual) that rests upon the perceptions of a set of stakeholders who are making broad evaluations on past activities and who hold expectations of future behavior (Harvey, Morris, & Smets, 2020). These perceptions of capability and character (Mishina, Block, & Mannor, 2012) are often made in relation to a group of competitors or with reference to past actions (Fombrun, 2012). Reputation is a socially constructed intangible asset that can be positive and/or negative and is generally stable and enduring (Walker, 2010). Building on the literature, I define reputation as:

The multiple perceptions of an organization made by different stakeholders, based on their evaluations of the past capabilities and character of the organization, and their assessment of its ability to provide future contributions.

Framework for Understanding Multiple and Conflicting Reputations

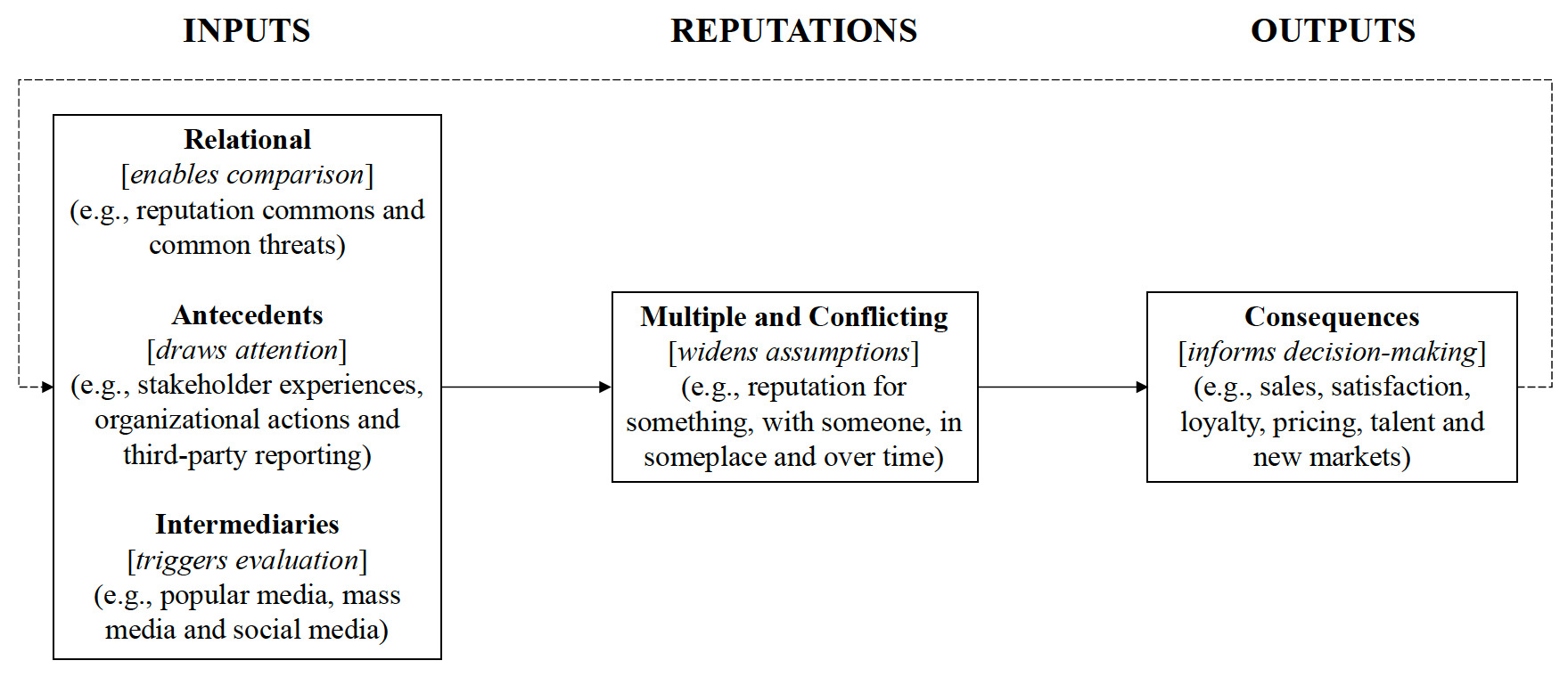

I now outline a framework that is both evidence-based and practical in its approach for helping leaders to understand multiple and conflicting reputations (see Figure 1). There is a large body of literature on the causes and consequences of reputation, which I capture under Inputs and Outputs. Under inputs, I use the term Relational to highlight that an organization’s reputations are compared to its competitors. I use the term Antecedents to capture the experiences, actions and reporting of stakeholders. This links to Intermediaries who are third parties such as popular, mass and social media who influence the formation of multiple and conflicting reputations. Under the banner of Reputations, I make the argument that despite the simplicity and seductiveness of describing organizations as having a single harmonious reputation, growing evidence suggests that organizational reputation is both multiple and conflicting. Finally, under Outputs, I explain the consequences of multiple and conflicting reputations for organizations, which can be positive and/or negative. I now detail the literature from which this framework has been created and provide practical considerations for leaders of global organizations.

Inputs

Relational

Organizations do not exist in a vacuum and their reputations often depend on how they compare to others in a global context. Think Coke versus Pepsi, or Airbus versus Boeing. This could be through a stock market performance, a position in a ranking table or the perceived quality of its products or services. However, when there is a risk of contagion, note how quickly competitors run for the hills, as was witnessed when energy companies distanced themselves from BP during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill to signal that their safety practices were starkly different from the perceptions of BP’s safety practices. Organizations can look better or worse when compared to their competitors or in relation to their past activities (Barnett & Hoffman, 2008). For example, they can face a ‘reputation commons problem’ (King, Lenox, & Barnett, 2002) such as data protection or fake news in the technology sector. In 2020, FireEye, the highly regarded cyber security firm that is used by companies and governments around the world to protect them from being hacked, was itself hacked by a sophisticated attack. This kind of incident represents a wider threat beyond reputation, known as a ‘common threat’, which is not exclusively about reputation or particular to one organization, but common to multiple sectors (Harvey, Beaverstock, & Li, 2019). Other examples include the global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 and the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 and 2021.

Both reputation commons problems and common threats are important because they extend beyond a single organization or location and require a response across international borders (e.g., Volkswagen’s emissions scandal). A relational approach is an important reminder for leaders to consider their activities not only in relation to their past, but also in the context of what other organizations are doing. The rapid expansion of Huawei’s 5G network alongside US-Sino geopolitical tensions, for example, has brought into sharp focus the lagging development of alternative providers in many other developed countries such as the UK, France and Singapore. Organizations do not operate in a national vacuum and this becomes even more significant when considering the antecedents of reputation.

Antecedents

There is an established literature on the antecedents of reputation. Fombrun (2012), for example, argues that an organization’s reputation derives from prior stakeholder experiences, attitudes and perceptions, which may or may not be consistent across different groups. He argues that reputations stem from three principal sources: the experiences stakeholders have with the organization (e.g., the experience of customers using Hilton hotels), the organization’s actions to influence stakeholder perceptions (e.g., the impact of a Coca Cola Christmas commercial on customer sentiments and purchasing) and the specialized coverage of the organization by third-parties such as journalists, analysts and ranking agencies (e.g., Impossible Foods winning Inc.'s 2019 Company of the Year Award, leading to greater awareness of the company’s plant-based substitutes for meat products). An important stakeholder who influence the reputations of organizations are intermediaries.

Intermediaries

There are limits with how far organizations can directly manage their reputations because a wide range of intermediaries influence their reputations. Examples include, first, the mass media’s powerful role in influencing organizational reputation given the exposure of reporting to wider audiences (Deephouse, 2000). Importantly, the media not only advertise and report on the actions of organizations, but shape perceptions through editorial decision-making and journalistic interpretation (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990). Consider, for example, how the global media responded in 2021 to Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s interview with Oprah Winfrey about the British Royal Family. The media also influence perceptions through prominent awards (e.g., Forbes’ The World’s Most Reputable Companies). Second, the role of social media has shifted the formation of organizational reputation from a relatively homogeneous and linear model to one that involves a growing number of actors, networks and co-production of multiple reputations (Etter, Ravasi, & Colleoni, 2019). Most industries have many social media influencers who operate across multiple platforms (e.g., Instagram and YouTube), making regular commentaries on products and services. James Charles, for example, is a celebrity makeup artist and blogger with 24.4 million subscribers on YouTube and 24.8 million followers on Instagram. Such influencers can generate significant return on investment for organizations because followers tend to trust reviews by influencers more than traditional corporate marketing claims.

Reputations

Multiple and Conflicting

Organizations can find themselves having multiple and conflicting reputations, which reflects the many perceptions of different stakeholders. I have captured these multiple perceptions in my framework under inputs: the different ways they are compared (relational), the varying stakeholder experiences (antecedents) and the disparate ways they are analyzed by third parties (intermediaries). There can be benefits and burdens for organizations when building and managing their reputations, particularly if they are prominent and global (Zavyalova, Pfarrer, Reger, & Hubbard, 2016). Note, for example, how a prominent organization such as Apple Inc. receives significant media attention, both when it releases a new product such as an iPhone or iPad, and when it faces a scandal such as tax avoidance or poor labour practices. Or notice how some stakeholder groups love the ubiquity, price or nature of the McDonald’s menu around the world, whereas others are vociferously outspoken on the poor quality of the fast food, the health implications and the environmental impact.

There are countless examples of prominent organizations who have experienced catastrophic and rapid reputation loss such as Enron, Parmalat, Lehman Brothers and Wirecard. Empirical research has also examined how start-ups can swiftly transition from having no reputation to a positive reputation through a process of ‘reputation borrowing’ (working with other organizations) or ‘reputation by endowment’ (working with other founders) (Petkova, 2012). Warren Buffett’s saying: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it” has shown to be true around the ‘five minutes to ruin it’, but the ‘It takes 20 years to build a reputation’ is coming under question with products, services and capital being developed at breakneck speed. Hopin, the virtual events company, for example, started in 2020 with four employees and rose to be valued at $2 billion in under a year, becoming one of the fastest growing start-ups (Bradshaw & Kruppa, 2020). Even with established organizations, the global response to the Covid-19 pandemic has led at the time of writing to the development of three vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech; Moderna; University of Oxford-AstraZeneca) in around 10 months, which ordinarily would take a decade (Gallagher, 2020). This suggests that the speed that reputation can be built (and potentially damaged and destroyed) is accelerating, which reflects wider structural changes in how multiple reputations are formed (Etter et al., 2019). This is both an opportunity and a risk that leaders must recognize and manage.

Reputation is often considered as singular, for instance the reputation of China (country), London (city), Silicon Valley (region), Morgan Stanley (company) or Jeff Bezos (CEO). However compelling an experience, story, award or ranking might be for forming a single reputation, it is problematic because reputation is dynamic and can vary rapidly in both positive and negative ways (Harvey, Tourky, Knight, & Kitchen, 2017; Helm, 2007). There have been a wide-range and growing number of reputation rankings in the last few decades, ranging from those that focus on individuals (e.g., Forbes), organizations (e.g., Fortune), cities (e.g., The Economist’s Liveability survey) and countries (e.g., HSBC’s expat explorer survey). What these surveys have overlooked is how different forms of reputation intersect, how entities have multiple reputations and how stakeholders consider different factors as salient to them (Velamuri, Venkataraman, & Harvey, 2017). For example, a Vice President of Engineering in Taiwan may have a strong desire to work for Sundar Pichai (CEO of Alphabet Inc. and its subsidiary Google) at Googleplex, Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California, but no desire to live in the San Francisco Bay Area or in the US. These conflicting views will impact on her decision to move or stay.

Reputation remains poorly understood in the global arena and it is not clear how and why it differs (Deephouse, Gardberg, & Newburry, 2019). When studying the reputation of a global management consulting firm, Harvey, Tourky, et al. (2017) found three forms of reputation varied. First, the reputation for something. For example, in some countries such as Germany, its reputation was particularly strong in the areas of cost cutting and restructuring, whereas in other countries such as France and China, its reputation was strong in innovation and strategy, respectively. Second, the reputation with someone focuses on how the firm is perceived by different stakeholders, which varied depending on the position they held and their geographic location. Third, the reputation of an organization varies across geographic location and sometimes this can lead to competition, tension or even informal tiering between different offices of the same organization. Starbucks, for example, has a very successful and popular chain of coffeehouses, with a strong and iconic brand. However, while it has succeeded in expanding abroad in some countries such as India, it has failed in others such as Australia by not sufficiently adapting to local cultures, tastes and pricing.

Although reputation is not static, it can be hard for organizations to change over time (Schultz, Mouritsen, & Gabrielsen, 2001) because often clients, competitors and employees do not accept the new claims organizations make about themselves (Harvey, Morris, & Müller Santos, 2017). For example, it took time for the Big Four accounting firms (PwC, Deloitte, EY and KPMG) to persuade clients that in addition to their historical expertise in audit, taxation and actuarial services, they also had credible expertise in management consulting. Hence, when embarking on reputation change, leaders need to carefully communicate with and persuade different stakeholders to avoid a disconnect between their intended image (“what does the organization want others to think about the organization”) and their reputation (“what do stakeholders actually think of the organization”) (Brown, Dacin, Pratt, & Whetten, 2006: 102).

Outputs

Consequences

Leaders need to focus their attention on reputation because the consequences are significant (Fombrun, 2012; Rindova, Williamson, Petkova, & Sever, 2005; Walsh, Mitchell, Jackson, & Beatty, 2009). The benefits that organizations can accrue from a positive reputation include higher sales, customer satisfaction and loyalty, positive word of mouth, charging higher prices, positive stakeholder assumptions around quality, the ability to attract and retain talent, and advantages with moving into new markets, to name only a few examples. However, there are also major ramifications for organizations who experience negative reputations, which can include shock, damage or even demise. Ultimately, all stakeholders consider reputation because it helps inform their decision-making, whether they are potential employees, investors, customers, partners or regulators. This becomes even more complex to understand when organizations exist across multiple borders and stakeholders will turn to crude proxies of reputation.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Leaders of global organizations need to pay careful attention to the inputs and outputs of multiple and conflicting reputations (see Figure 1), particularly given that reputations are social evaluations of intangible assets that organizations cannot fully control or own (Pollock, Lashley, Rindova, & Han, 2019). There are three interrelated inputs to consider. First, relational factors that enables comparison of organizations. Second, antecedents that draw attention to organizations. Third, intermediaries that trigger various evaluations of organizations. These inputs can contribute to organizations having multiple and conflicting reputations that will widen assumptions among different groups around their relative strengths and weaknesses. While the emergence of reputations can sometimes be outside the control of leaders, how such reputations are managed will impact on the reputations of organizations in the long-term. This is particularly challenging and salient for organizations operating across international borders where reputations can be even more diverse.

Building on Figure 1, I suggest four sequenced recommendations for leaders (see Table 1). First, address what is salient for stakeholders in relation to the organization (e.g., capability, character or contribution) alongside what the organization considers salient about its stakeholders. Second, balance compromise with intransigence to build trust with stakeholders to avoid tensions (Siedlok, Elsahn, & Callagher, 2021) and being misconstrued (Sisifa & Stringer, 2021). Third, manage the brand, communication and public relations activity from the headquarters as a networked hub to ensure a coherent global reputation from the activities of the subsidiaries, rather than encouraging them to decentralize their own in-country activities which risks causing global incoherence. Finally, enhance the organization’s credibility by helping internal and external stakeholders to understand the connection between its past and present as well as with its planned future global activities.

In summary, reputation is significant for leaders to understand in a global context because although their organizations may have a solid local investor, employee and customer base, opportunities and threats are changing rapidly at a global level, which require awareness, response and careful management.

About the Author

William S. Harvey is Professor of Management and Associate Dean at the University of Exeter Business School. He is an International Research Fellow at the Oxford Centre for Corporate Reputation and Chair of the Board of Libraries Unlimited. Will advises leaders on reputation, talent management and leadership.