Corporate reputation represents stakeholders’ evaluations of an organization based on its past and likely future actions as compared to the stakeholders’ norms, values, and expectations (Rindova & Martins, 2012). Reputation is frequently one of the top concerns of top managers. Despite extensive literature on the antecedents and consequences of firm-level reputation (e.g., Fombrun, 1996), multinational enterprise (MNE) managers face challenges managing reputations across borders. As such, MNE managers need guidance to better adapt to the societal contexts within which reputations are established (Deephouse, Newburry, & Soleimani, 2016). Our ability to advise these managers would benefit from an increased understanding of the factors that influence reputation development across global contexts (Gardberg, 2006; Newburry, Deephouse, & Gardberg, 2019) and of the ways that positive reputations obtained in one country can be transferred to others.

While there is a proliferation of academic and practical advice on the management of reputations in a general sense, our understanding of best practices for managing reputation in a global setting remains much more underdeveloped. What we know about corporate reputation in a single country may not be good advice for engaging with the complexity of multiple stakeholders spread across different countries. Moreover, this takes place in a communicative environment where information about an MNE’s actions anywhere in the world could become widely shared. This special issue of AIB Insights will focus on applied and actionable insights regarding the management of reputation across borders.

Key Components in Transferring Reputation across Borders

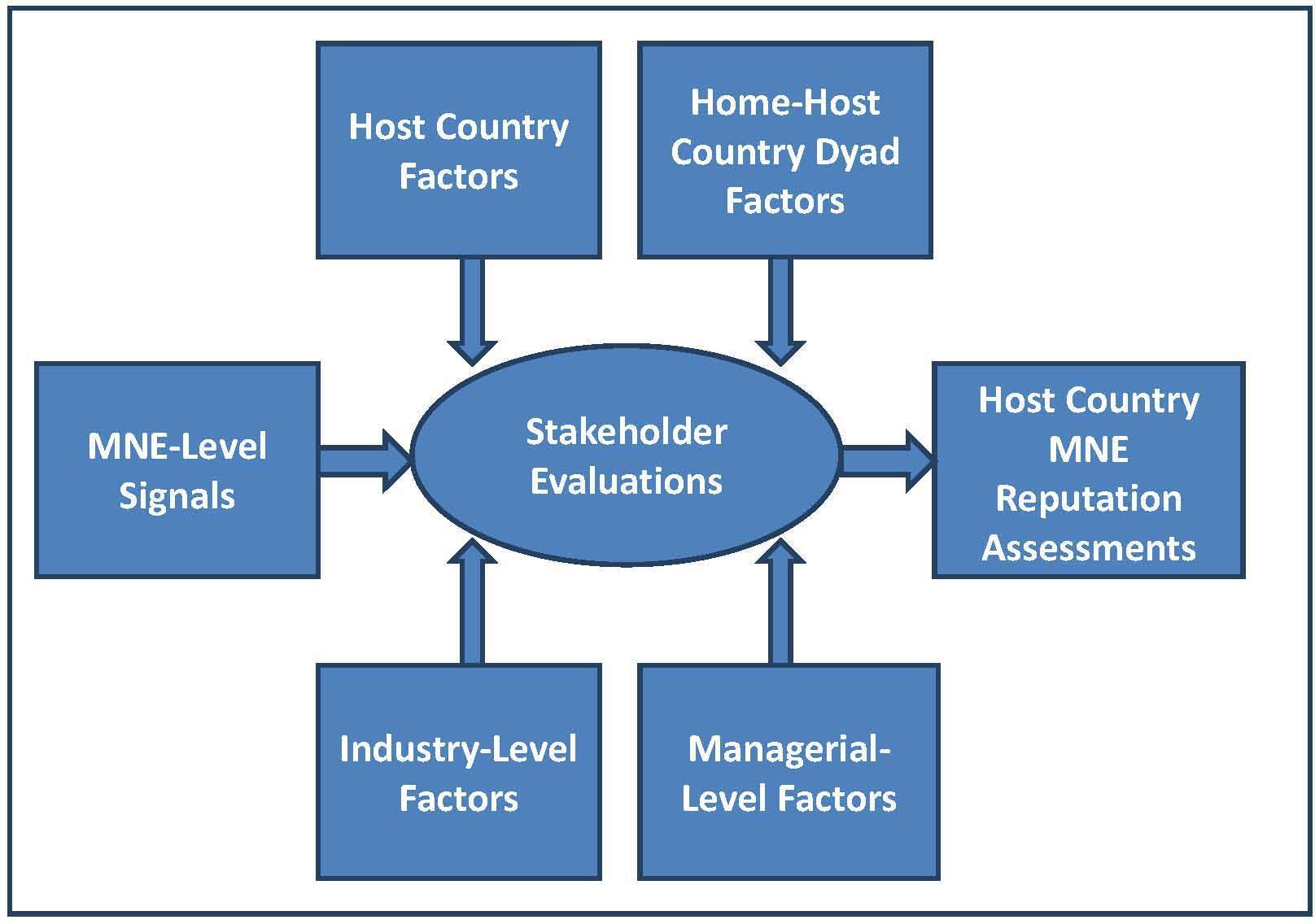

Before delving into the specific articles contained within this special issue, we highlight some key factors inherent in an MNE’s efforts to manage reputations across borders. Several are addressed in articles in the issue, but certainly not all, creating many opportunities for future research in this important and growing area. Figure 1 provides a simplified conceptualization of the process by which an MNE’s reputation transfers to a host country.

At the core of the figure, stakeholders within a host country interpret MNE-level signals to assess an MNE’s reputation, consistent with much reputation theory within a domestic context. These signals could relate to factors traditionally studied in a single-country, such as profitability (e.g., ROA), MNE size, market share, corporate social responsibility (CSR), (social) media presence, etc. Other factors that could become more important in international settings include international experience, the global touch of an MNE’s products and brands, an MNE’s degree of internationalization, and its strategy with respect to its global operations (e.g., International, Global, Multidomestic, or Transnational).

Factors inherent to the host country complicate the assessments of MNE reputation in that host country. These factors that influence their evaluation of MNEs include country development level, country globalization level, national institutions and culture, and ethnocentrism within a country (Deephouse et al., 2016). The nature of the media and other informational intermediaries within a country could also influence the degree to which (reliable) information regarding an MNE and its products is available in a host country to assist in reputation assessments.

Relations between the home and host country generate another set of factors. For example cultural or other institutional differences (e.g., the CAGE framework, which addresses cultural, administrative, geographic and economic distances between countries) could impact the interpretation and assessment of MNE signals (Berry, Guillén, & Zhou, 2010; Ghemawat, 2001). Host country perceptions of the country of origin may also be present (Newburry, 2012). Country reputation may play an important role, particularly when MNE-level information is lacking and reputation assessors rely on stereotypes regarding a country and its products. This is a particularly prevalent issue when examining emerging markets and their MNEs.

Industry factors may also influence the assessment of MNE reputations in a host country. These include the global nature of the industry, whether it operates in a B-to-C versus B-to-B space, and whether it competes based on differentiated versus undifferentiated products (e.g., commodities). Also important is whether an industry is one which produces credence goods and services, which are difficult to evaluate even after the good or service is rendered (e.g., some elements of health care), or experience goods (e.g., restaurants).

Many managerial factors may apply. These include the degree to which managers possess a global mindset, their international experience (e.g., living and/or working abroad), international training, cultural intelligence, and psychological and personality traits (e.g., openness). All could influence the ability of managers to develop their MNEs’ reputations in host countries. More broadly, international diversity in the management team of an MNE might also enhance the creation and transfer of reputation.

Most MNEs are managing their reputations across multiple host countries. Tensions between stakeholder expectations may be accentuated in host countries with different norms and institutions; for instance, CSR activities that are valued in one host country may be inappropriate in another (Gardberg & Fombrun, 2006). Managers and researchers could replicate Figure 1 for each host country, while recognizing the commonalities among the factors.

Issue Articles

We hope that the discussion above helps in creating a roadmap of opportunities for more research in this area. We now introduce the four articles in this special issue dealing with issues related to managing reputation across borders, along with one article related to the prior journal issue on Research Methods.

The first article, by William S. Harvey of the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom examines “Managing Multiple and Conflicting Reputations in Global Organizations”. The author develops a framework where leaders need to consider three interrelated inputs that impact reputations and ultimately the consequences of these reputations. These inputs include relational factors, reputation antecedents, and the actions of intermediaries, which can result in multiple and often conflicting reputations. In so doing, the article touches many of the components of Figure 1. The article concludes with some practical considerations for managing the components of the framework, along with a set of four sequenced recommendations.

The second article by Keith Kelley of the University of Michigan-Flint and Yannick Thams of Florida Atlantic University, both in the United States, is titled “Creating Shared Reputational Value while Managing Informational Asymmetries across Borders: The Platform Business Paradox”. The authors examine the interplay between the platform business model and shared reputational value, and in so doing, focuses primarily on the MNE-level and Industry level components of Figure 1. The authors identify a paradox in which platform economies reduce informational asymmetries, on one hand, but also serve to make reputation signals less precise due to the large degree of shared value among platform members. This article advises practitioners on how platform business models impact the creation of shared reputational value, while also examining challenges of operating internationally through the lens of the CAGE framework (Ghemawat, 2001).

The issue’s third article is by Theresa Bernhard of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany; it is titled “If It Works Here, How Can We Make It Work Anywhere? Reputation transfer across borders”. This article develops insights from interviews with German managers regarding the transfer of MNE reputations abroad during the internationalization process. Based on interviews with corporate reputation specialists, the author finds that a variety of stakeholders in the home country need to understand an MNE’s reputation. These stakeholders then must be empowered as reputation ambassadors, who can communicate credibly with stakeholders in a new host market about an MNE’s positive reputation. By focusing on stakeholder engagement across borders, this article straddles the space in Figure 1 between stakeholder interpretations and the micro-level relations between members of home and host countries. Social media can also be a valuable tool for the transfer of reputation across borders.

The final article in our Management Reputation Across Borders theme is by James Agarwal and Oleksiy Osiyevskyy of the University of Calgary in Canada and is titled “Organizational Reputation for Customers: Key Insights on Leveraging Reputation in Global Markets.” The authors contrast the concept of national culture with individual culture. The construct of individual culture would be considered self-contradictory by many international business and/or culture scholars given that culture is generally defined as a collective construct. However, this construct has been used in some psychology research to refer to individual-level mental cognitive structures, in line with scholars such as Gould & Grein (2009). The authors use these constructs to examine how firms can translate favorable organizational reputations into valuable organizational outcomes. In so doing, they highlight the stakeholder interpretation and Host Country components of Figure 1. They present a conceptual framework where customers perceive three distinct facets of organizational reputation: product & service efficacy, market prominence, and societal ethicality, which build into a higher level concept of a company’s organizational character. They then provide recommendations regarding how national and individual culture impact MNE actions to form and leverage their reputations in global markets.

In addition to the four reputation articles, this issue also features an article that complements our last issue, the forum on Research Methods in International Business (2021, Vol. 21, Issue 2; see Aguzzoli, Gardner, & Newburry (2021) for an overview). Amir Qamar and John Child, both from the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, present “Grand Challenges within IB: Conducting Qualitative Research in the Covid Environment.” In the article, the authors present international business (IB) scholars with a ‘grand challenge’ of conducting research to inform theorizing within the new context of the Covid-19 pandemic. They advise how this research needs to be qualitative, and then they discuss methodological implications of conducting qualitative research under pandemic-related restrictions, addressing issues related to primary and secondary qualitative research in this environment.

Overall, we hope that you enjoy this issue, which is our third issue of 2021. Please continue to submit your applied international business work to AIB Insights!