Introduction

International business (IB) is ubiquitous in our lives, as evidenced by the growth of international companies, products, and services that most of us are exposed to on a regular basis, sometimes inadvertently.[1] At the same time, after decades of increased globalization, we are seeing greater anti-globalization and economic nationalism sentiment take hold throughout much of the world (Stiglitz, 2002, 2016). Disruptions such as the COVID-19 global pandemic and ensuing financial crisis are showing uneven recovery across different parts of the world, especially between developing and developed markets (UNCTAD, 2021a, 2021b). These trends highlight the complexities involved in IB, and the criticality of having a field expressly focused on them.

The IB academic field is thus needed now more than ever, both in terms of teaching - to help our students develop a global mindset (Paik, 2020), and in terms of research - to study and understand the richness and complexity of international phenomena (Shenkar, 2004; Sullivan, 1998). This requires that universities have a robust IB faculty, ideally organized within IB departments, which can use their expertise to develop strong IB courses and programs.

The results of the 2020 AIB Curriculum Survey show that although the field of IB has made significant progress, implementation of IB across schools has been uneven (Kwok, Grosse, Fey, & Lyles, 2020). The survey, which covers 192 business schools worldwide,[2] provides valuable insights as to why this is the case. AACSB requires that a global component be included in the curriculum, but the ways it can be implemented are broad, leading to wide differences and gaps in the development of IB across schools. For instance, IB can be taught either through stand-alone IB courses (i.e., general IB courses or specialized IB courses) or by adding IB content to extant functional courses (e.g., a Management or Marketing course with some IB coverage). A significant amount of the growth in IB in schools has been through the latter approach. Importantly, the survey found that the greater the number of stand-alone IB courses offered by a school, the greater the amount of IB knowledge students obtain during their program. On the other hand, the number of courses where IB is added to extant functional courses had no significant effect on the IB knowledge of students by graduation. This may occur in part because faculty teaching functional courses may vary in the level of their international expertise. Similarly, there is a longstanding debate on whether IB should be a stand-alone subject area or where the adjective “international” should simply be subsumed within the functional areas of business (e.g., international marketing, international accounting, etc.). Relatedly, this decision often informs whether IB departments are needed, or IB faculty can be placed in functional departments. The survey identifies four ways IB faculty can be organized: in functional area departments without identification as IB faculty (49% of schools), in functional area departments with identification as IB faculty (16%), in a matrix structure where the faculty are in functional area departments but are also part of an IB center/institute (19%), and in stand-alone IB departments (16%). With nearly half of the schools pursuing the first approach, this creates a disincentive for scholars to enter the IB field, given the higher number of academic jobs available in the functional business areas. For those that do enter and are placed in a functional department, there is a further disincentive to publish IB work, as international research is time consuming and difficult and non-IB colleagues may not appreciate these challenges. It can also be difficult to publish international research in the top field journals. Indeed, the survey discusses how the percentage of published academic work with explicit international content in the top 20 academic journals is very slim. Related to the debate on whether IB should be considered a self-standing field of research and teaching is whether the Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS), the top IB journal, is considered a top journal. The sample in the survey shows that 69% of the schools worldwide consider JIBS a top journal and that number is 62% in the US and Canada. This creates a further disincentive to specialize in IB if not all universities accept JIBS as a top-tier journal despite its low manuscript acceptance rate, very high impact factor, inclusion in both the FT50 and UT Dallas 24 journal rankings, and a four star ABS ranking.

As this survey shows, the IB field could be in peril and hampered in its future growth potential if it fails to convincingly show what makes it unique, important, and relevant. Building on prior work focusing on outlining the domain and role of IB (e.g., Littrell & Rottig, 2013; Rottig & Mezias, 2017a) and developing greater legitimacy and relevance for the field (e.g., Rottig & Mezias, 2017b), this article is designed to help address this issue by developing a simple but powerful framework that displays the value of IB as a field.

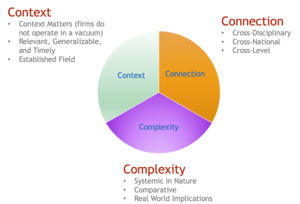

What makes the IB field unique and important? The three C’s of IB: context, connection, and complexity. Context denotes the importance of examining firms in their environments and not in a vacuum. Connection addresses how the field links disciplines, nations, and levels of analysis. Complexity refers to how the field is systemic by its very nature. We apply this framework to the multinational enterprise (MNE) to display the richness of our field. We then discuss implications of the 3Cs framework for various key stakeholders and close with areas for future work.

The Three Cs of IB

IB is unique in its focus on context, connection, and complexity. We discuss each of these interrelated aspects below and summarize them in the 3Cs framework presented in Figure 1. Furthermore, Table 1 provides examples of how each of these aspects applies to IB researchers, educators, practitioners, and policymakers. This helps to show how the framework can serve as a valuable pedagogical tool.

This section briefly introduces each of the 3Cs, while the next section develops them further by applying the framework to the MNE.

Context

A key notion in the IB field is that context matters (c.f., Foss & Pedersen, 2019). Firms and context interact as firms do not operate in a vacuum or in isolation. The field routinely examines context through formal and informal institutional frameworks, cultural frameworks, and contextual changes over time. Other business fields may consider it as a secondary aspect, whereas IB sees it as central. Indeed, IB uniquely brings context into play as a focal dimension making research relevant, generalizable, and timely. Examining firms in a single context provides narrow findings that are typically not generalizable across contexts. IB allows for a broader view that crosses borders and other domains. IB is also particularly relevant to what is happening in the world today. It often examines big questions, instead of just focusing on incremental work (e.g., Buckley, 2020). In addition, IB has the advantage of being an established field. If one agrees that the interaction of context and business matters, then it needs to be examined in an organized way. IB serves as the established field to accomplish this.

This point cannot be overstated, as suggesting that IB could simply be subsumed into other business disciplines or departments would no doubt lead to less attention to context as a central element in research, teaching, and ultimately practice. IB academics, who are grounded in the importance of context, are therefore particularly well suited to study and train future business leaders and policymakers in the nuances of context, and to help them develop a global mindset that can appreciate differences and become more open to global business and economic opportunities (c.f., Kwok et al., 2020).

Connection

Connection refers to how IB bridges different disciplines, nations, and levels of analysis (c.f., Eden, 2008). It also connects each of these aspects dynamically, examining changes over time. First, IB is cross-disciplinary or interdisciplinary by its very nature, as the study of context requires considering societal, economic, political, etc. aspects. IB helps connect disciplines and scholars within business (e.g., international management, international marketing, international finance, international accounting, international supply chain management, etc.) and between business and outside fields (e.g., sociology, psychology, anthropology, political economy, economics, political science, economic geography, international affairs, etc.). Second, IB is cross-national as it examines questions across borders and other geographic aspects. It examines aspects such as flows of knowledge and other resources across geographic space. Third, IB is cross-level as it allows for research that crosses levels of analysis. Among others, these can include the global, supra-national, regional, national, industry, firm, department, work group, and individual levels of analysis.

IB thus provides a unique space within business academia that encourages bridging otherwise disconnected conversations across disciplines, nations, and levels of analysis (e.g., through AIB’s portfolio of academic journals: JIBS, JIBP, and AIB Insights). Furthermore, IB education provides a setting that facilitates creating linkages and knowledge integration for students across courses and other areas. This can lead to managers and public policy practitioners trained in IB who are better grounded in an understanding of connectivity across different domains. As a result, IB can help enrich research, teaching, and practice beyond its own field in ways that are not always evident.

Complexity

Building on the first two Cs, it is the contextual and comparative nature of IB that leads to its ability to examine complex systems, structures, and relationships in a meaningful manner (c.f., Eden & Nielsen, 2020). Other business fields also examine organizational complexity, but IB goes beyond by adding to this the contextual and connective elements described above, as well as the systemic, comparative, and real world elements described here.

In particular, IB is systemic in nature. Systems theory suggests that a whole is greater than the sum of its parts, as it also requires considering the interactions between them. For instance, an NGO involved in giving tiny loans to mostly unbanked entrepreneurs (such as Grameen Bank) is more than just an intermediary obtaining grants or deposits that it redistributes to its target segment, as it has to bring together international philanthropic groups, local governments, village leaders, social workers and educators, to create systemic change in underserved communities. Its ability to combine these elements creates something far more complex than what just being an intermediary between two parties can achieve. Relatedly, IB is comparative in that it allows for research that examines differences and similarities across units of analysis (e.g. organizations, nations, institutions, regions of the world, etc.), constructs, categories, theories, etc. Through this focus on comparative analysis, the field seeks to understand why otherwise similar firms or other business actors are organized in different ways across countries.

As a result of these factors, IB provides real world implications. Examining firms in a vacuum misses the systemic social, political and economic embeddedness of firms, often leading to findings that are not useful in the real world. IB avoids this trap by considering firms as part of larger systems. This allows IB scholars to examine highly complex theory and phenomena, IB educators to train students to develop systemic and critical thinking skills, and IB practitioners and policymakers to be better prepared for the complexities of today’s global environment. Systems thinking is thus required in IB research, teaching, and practice, leading to greater complexity, but also greater richness and usefulness.

IB as a Field Embracing the 3Cs

Of course, not all IB research projects capture the full intricacy of the factors in the 3Cs framework, but they do together as a field. IB creates opportunities for teaching and research across business fields and disciplines, across countries, across levels of analysis, and over time. IB as a field is thus uniquely characterized by context, connection, and complexity.

Applied Example: The 3 Cs and the MNE

Figures 2-4 show the MNE as an ideal example applying context, connection, and complexity to IB.[3] This example serves to show how IB allows for a study of complex questions beyond that of any single field. It shows how IB is systemic, interdisciplinary, cross-level, etc. It is a powerful visual way to show how rich and far reaching our field is. This example also allows us to delve deeper into each of the 3Cs in an applied manner.

These figures illustrate how context, connection, and complexity come into play in IB. These figures are built step-by-step in sequential order, to help show how the completed diagram in Figure 4 is constructed. In particular, Figure 2 first shows the parent firm with individuals nested across functional areas and then adds the home country environment of the parent firm. Figure 3 then builds on this by adding the firm’s international subsidiaries, each with individuals nested across functional areas, as well as the host country environments for each of these subsidiaries. Figure 4 further builds on this by adding the global environment. Finally, Figure 4 adds the relationships and knowledge flows between the parent firm and its subsidiaries. Furthermore, IB considers dynamic effects and change over time across the full system.

More specifically, the figure illustrates context by showing the national environment of the parent firm and of each foreign subsidiary, as well as the global environment within which the full MNE is nested. It illustrates connection by showing how it is cross-disciplinary (with functional areas within the firm and political/economic/social/etc. factors being considered), cross-country (with headquarters and affiliates across home and host countries), and cross-level (with individuals nested within functional areas, nested within firms, nested within countries’ cultural and institutional contexts, nested within the global cultural and institutional environment). It illustrates complexity by showing how examining the MNE requires systemic thinking that considers all of these factors and their relationships in a holistic manner.

This helps to illustrate that contrary to functional fields that often examine their areas separately, IB requires systemic thinking where the complex relationships between business units, functional areas, national environments, and the global environment are all considered in unison.

This is what makes IB so fascinating yet so challenging. It avoids examining companies in a vacuum –assuming away context, connection, and complexity– which would be at the cost of reducing relevance in its findings. Systemic thinking is challenging but critical for relevance.

Applied Insights: The IB Academic Community

The direct result of the field’s focus on context, connection, and complexity is a distinctive academic community. The IB community is a unique group of scholars within business academia, which provides a forum for collaboration across geographies, disciplines, theoretical frameworks and methodologies, levels of analysis, and generations of scholars. It is comparable to communities in other social sciences such as international affairs and international political economy, but distinct within business. One may find parallels in some or other of these points with other business academic communities, but the IB community is unique in comprising all of these attributes.

Geographies (Global Mindset)

IB is a global community rich with exchange of information and other resources across nations and other geographic settings. Other fields may have international collaborations (e.g., in terms of teaching and research), but it is something that is embedded in the DNA of our field, which creates a very special community of globally-minded individuals.

IB academics are particularly well prepared to work in the development and teaching of international programs (e.g., study abroad, international internships), which are a staple of many universities. Indeed, IB scholars are trained to think with a global mindset, allowing them to help students develop a similar mindset, which can provide an important advantage in their careers. This global mindset also means IB scholars are particularly well suited for the type of research that is conducted in the field (c.f., Kwok et al., 2020).

Disciplines (Interdisciplinary)

Given its interdisciplinary nature, IB serves as a broad umbrella field providing a forum for scholars from across fields – within and outside of business – to come together in their research and teaching pursuits (c.f., Kwok et al., 2020).

Theoretical Frameworks and Methodologies

Given its interdisciplinary nature, the field is ecumenical about theoretical frameworks and methodologies, allowing for a community of scholars with a broad perspective.

Levels of Analysis

IB is also a community of scholars spanning work at and across different levels of analysis. These levels span from the individual, workgroup, and department levels, all the way up to the firm, national, and supranational levels. This allows for knowledge exchange and systemic thinking across levels.

Conclusion

This article proposes that what makes IB unique and important as a field are three C’s: context, connection, and complexity. It contributes to the literature by providing this in a simple but rich framework. It also applies this to the MNE, examines implications for various stakeholders, and discusses the importance of the IB community. Future work can extend this in various ways, such as by applying the 3Cs of IB framework to ‘big questions’ and ‘grand challenges’ facing the world today (Buckley, 2020; Eden, 2020; Rottig & Mezias, 2016). We thus hope this article will be of great benefit to our fellow colleagues.

Acknowledgements

This project was commissioned by the AIB Executive Board (President Chuck Kwok and President-Elect Jeremy Clegg; Vice Presidents Program Rebecca Piekkari, Gary Knight, and Maria Tereza Leme Fleury; Vice Presidents of Administration Helena Barnard, Luis Alfonso Dau, and Rebecca Reuber; and Executive Director Tunga Kiyak), with the support of the other members of the AIB Secretariat (Anne Hoekman, Kathy Kiessling, Dan Rosplock, and Irem Kiyak). It was developed by the AIB Uniqueness Task Force (composed of the authors of this paper). Detailed information on the origins of the project was not included in the paper for the sake of the double-blind review process and page length requirements, but is available upon request from the authors. We thank Editor Elizabeth Rose and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive feedback. We are also grateful for the preliminary feedback from Editors John Mezias and Bill Newburry, as well as from JIBS Editor Alain Verbeke. We also thank the authors of the 2020 AIB Curriculum Survey (Chuck Kwok, Robert Grosse, Carl Fey, and Marjorie Lyles) for sharing their results with us. This project has been a team effort that would not be possible without the commitment and support of each of the people listed in these acknowledgements. This work has been funded in part by the Robert and Denise DiCenso Professorship and the Center for Emerging Markets at Northeastern University.

About the Authors

Luis Alfonso Dau (L.Dau@northeastern.edu) is an Associate Professor of International Business and Strategy and the Robert and Denise DiCenso Professor at Northeastern University. His research focuses on the effects of institutional processes and changes on the strategy and performance of emerging market firms. He is also a Dunning Visiting Fellow at the University of Reading and a Buckley Visiting Fellow at the University of Leeds.

Sjoerd Beugelsdijk (s.beugelsdijk@rug.nl) is a Professor of International Business at the University of Groningen. He specializes in globalization and comparative cultural analysis. He is the research director of the global economics and management group, and has served as academic director of the undergraduate international business program at the Faculty of Economics and Business in Groningen. He is Reviewing Editor of the Journal of International Business Studies and a Fellow of the Academy of International Business.

Maria Tereza Leme Fleury (mtereza.fleury@fgv.br) is a Full Professor in the area of International Strategy and former Dean of FGV Sao Paulo Business School. She is the President-Elect and a Fellow of the Academy International Business. She is a Senior Professor at FEA/USP, as well as Dean from 1998 to 2006. Her research is in the areas of International Management, Competence Management, Culture, and Learning.

Kendall Roth (kroth@moore.sc.edu) is Senior Associate Dean for International Programs and Partnerships at the Darla Moore School of Business, University of South Carolina. He holds the J. Willis Cantey Chair of International Business and Economics and is a Fellow of the Academy of International Business. His research focuses on institutional and sociocultural approaches to understanding organization practices and routines within multinational enterprises.

Srilata (Sri) Zaheer (szaheer@umn.edu) is the Dean of the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota. She holds the Elmer L. Andersen Chair in Global Corporate Social Responsibility. Her research focus is on international business, a topic on which she has published extensively. She is a Fellow of the Academy of International Business, and a former Consulting Editor of the Journal of International Business Studies.

We see this for instance in the growing trade and investment flows across the globe for the past several decades. Even with the sharp dip in global trade due to the COVID-19 pandemic, UNCTAD projects international trade flows in goods and services of $28 trillion for 2021, which is 23% more than in 2020 and 11% more than at the height of 2018 (UNCTAD, 2021a). Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been slower to recover from the decline during the pandemic, but UNCTAD projects that FDI levels will soon be higher than before the pandemic (UNCTAD, 2021b). Relatedly, multinational enterprises (MNEs) are much more important and pervasive in our lives than most people realize. According to the Fortune Global 500 ranking, there are 10 MNEs with annual revenues exceeding a quarter of a trillion dollars (Fortune, 2022), while more than 150 nations have a lower GDP than that (World Bank, 2022). Similarly, 13 of these MNEs have more than half a million employees (Fortune, 2022), which is greater than the population of a number of countries (World Bank, 2022). We see the ubiquity of IB in the products we buy, as even those labeled as being ‘made in’ one country often are developed with materials and/or labor in or from other parts of the world and by companies with investors across the globe. We see it in global tourism and the increasing cultural interactions this entails. We see it in our consumption of media and entertainment with increasingly global content. Indeed, we are hard pressed to avoid it.

The sample includes AACSB and AIB member schools. In particular, the geographic scope of the 192 respondent schools is as follows: 72 from the US and Canada, 32 from Asia, 51 from Europe, and 37 from other parts of the globe.

The MNE has traditionally been one of the main units of analysis examined in IB, but it is not the only one. IB examines many other units of analysis at different levels, such as business groups, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), cultural diversity in workgroups, bicultural individuals, expatriate managers, and so on. Indeed, the field provides a ‘big tent’ that welcomes researchers interested in a broad range of areas. Future work can extend this article by examining how the 3 Cs framework applies to other units of analysis and areas of interest.