Introduction

Over the last century, despite imperfect immigration policies, developed countries successfully attracted the brightest minds from across the globe who contributed to their innovation and entrepreneurship. MNCs and non-profits – including universities – have consistently relied on migrants as resources to be employed in their productive and revenue-generation activities. In the last few years, however, legal immigration has been significantly restricted, and the impact of these restrictions has worsened since the onset of the COVID pandemic. The policies implemented to deter potential immigrants has stemmed the flow of talented migrants and created bottlenecks for firms recruiting talent from other countries, governments attracting foreign entrepreneurs, and, even universities, which have found it more difficult to attract talented foreign scholars and students. The authors of this paper, themselves have been transformed from ‘citizens’ to ‘aliens’ (and some of us back into ‘citizens’) in our journey of migration. Our research and experiences from various regions, cumulatively inform our perspectives on the importance of creating host-country ‘ecosystems’ that are inclusive of migrants.

Mass migration has fundamentally changed the racial, ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation (Raskovic, 2021), linguistic, and other forms of diversity of modern societies, markets, and workplaces. The international flows of people and the different capitals they transfer have been slowly gaining attention, but the diversity lens on these flows is yet to emerge (Stahl, Tung, Kostova, & Zellmer-Bruhn, 2016). When migrants move from one country to another, they carry a range of skills and perspectives, becoming superdiverse human assets that nurture innovation and stimulate economic growth. They also change their identity and status, which reframes them in the new context. Migration as a process produces formal and informal transformations of the individual, for example, changing their formal status to the otherness, becoming an ‘alien’, or not acknowledging their skills resulting in deskilling. Migration may also produce brain waste when businesses and society at large do not equitably include the incoming diverse talent. Under- and unemployed migrants constitute a sustainability problem as their human resources are no longer benefiting their home country, but their lack of participation does not allow them to contribute appropriately in the host country either or even send remittances home. Such impediments motivate many migrants, especially women (Aman, Ahokangas, Elo, & Zhang, 2021), to turn to entrepreneurship, often in businesses unrelated to their actual skills. This paper attempts to illuminate migration and diversity from the resource side, highlighting the potential and value they provide to host and home countries, while identifying concerns for management and policymaking deserving future attention. Thus, this paper focuses on two research questions: What is the value embedded in migrant superdiversity, for individuals, firms, and governments in their home and host countries? And, what structural gaps and organizational barriers need to be corrected to fully leverage the value of migrants superdiversity?

We first review research on migration from various diversity lenses, with the aim of exploring types of diversity amongst migrants and their inclusion/social cohesion in the host country. We identify issues related to migrant superdiversity based on gender, language, formal status and citizenship, as well as intersectionality. Our discussion includes views of migrants and diasporas as entrepreneurs and as MNC employees. Further, we illustrate opportunities and concerns about migrant transformations that contribute to management and policymaking. We hope to alert readers to the urgency and salience of migrant superdiversity in the context of international business as an emergent management topic, especially from an equity and inclusion lens.

Migrant Superdiversity

Superdiversity refers to differential legal statuses, their concomitant conditions, divergent labor market experiences, discrete configuration of gender and age, patterns of spatial distribution, mixed local area responses by service providers and residents, and the interaction of these (Vertovec, 2007: 1025). We focus here on three categories of diversity–gender, language, and formal status and citizenship–as well as on the intersectionality of these and other types of diversity.

Migrant Gender Diversity

In 2019, 48% of all international migrants were female, representing over 130 million migrant women (International Organization for Migration, 2020). The largest migrant cohorts were in Europe (82 million), North America (59 million), and Northern Africa and Western Asia (49 million). Despite these large numbers, the diversity of migrant cohorts and their untapped potential are currently not well captured. The lack of intersectional and interdisciplinary approaches results in an inadequate understanding of migration dynamics and the role of migrant women and minorities as contributors to global business and entrepreneurship (Aman et al., 2021). For instance, female migrants, often a minority group, typically face post-migratory brain waste and deskilling. Visible minority migrants and Muslim women migrants, especially, experience bottlenecks when entering host societies as economic actors (Elo, Täube, & Servais, 2021). Even highly skilled migrant women encounter career and integration difficulties, often triggering low-growth entrepreneurial activity. For instance, the recent COVID-19 pandemic highlighted a shortage of nurses and doctors in developed countries; yet, migrant nurses and doctors educated in their home countries–a large portion of which are women–could not render their services despite having the necessary knowledge and skills, mainly due to lack of work permits and licenses (Kothari, 2021). The lack of inclusive policies in receiving countries forces highly skilled migrants to resort to unskilled informal entrepreneurship, under-employment, or exiting the workforce.

Migrant Language Diversity

In the era of globalization, many people speak more than one language, either due to a multilingual origin, like in the case of migrants, or by learning languages. A multilingual origin enhances human capital resourcefulness, due to a more in-depth knowledge of the context in which the language is developed and spoken. Blommaert and Rampton (2011) observe that the concept of ‘superdiversity’ has replaced the old paradigm of migrants as simply ‘ethnic minorities,’ with one that acknowledges migrants’ multiple backgrounds and identities. The concept of ‘superdiversity’ challenges the assumption that we can accurately predict the socio-cultural characteristics and behaviors of ‘migrants.’ Research interest in diasporas captures this idea of ‘superdiversity’ by exploring theoretical and methodological issues related to language and migrant groups: languages become denaturalized, innovation and innovation dynamics including the ways in which individuals interact and communicate are far reaching. Cultural diversity encoded within languages is at risk, as many languages have become endangered in the last decades due to growing globalization. To preserve this diversity, multilingualism and multiculturalism must be considered valuable resources to be strategically leveraged, rather than simply something to be managed in human resource terms. Diverse languages enable and foster boundary crossing, understanding the other, interpreting behaviors, and doing business. For host countries, failing to leverage the multilingual and multicultural richness that migrants bring with them is another instance of brain waste. Hence, it seems pertinent to raise the need for theory development that revisits our current views on language, language-linguistic diversity (Shoham, 2019), and the roles of language as a communication tool and a valuable economic resource, in the contexts of home countries, intra- and inter-diaspora, and host countries.

Migrant Citizenship Diversity

Migrants and diasporas may have multiple formal identities (e.g., citizenships) that contribute to several economies simultaneously, which makes them particularly important for IB (Elo et al., 2021). Birth country diversity increases regional entrepreneurship and economic growth (Kemeny, 2017). Migrants bring to their adopted countries various resources and capabilities, alongside entrepreneurial knowledge and experience. The contemporary global business environment is associated with widespread migration of people moving from less developed to developed areas, especially, for political and economic reasons. These migration movements also highlight the intersectionality of migrant diversity such as religion, color, disability, sexual orientation, etc. Global migration forces countries to reexamine and reinvent the ways in which they socialize and educate diverse groups for citizenship and civic engagement. As business and policymakers identify ways to integrate migrants, it is important to acknowledge that mobile workers generate knowledge spillovers, transfer best practices, and help fill temporary and seasonal labor needs in destination regions. The recent COVID-19 pandemic food shortages highlighted the impact of foreign field workers in many developed countries. Currently, the special status of the Ukrainian refugees entering European Union countries enables them to work and venture without entering liminal spaces in transition experienced by refugees from other countries such as those from Syria.

Migrants as Employers and Employees: Bridging the Gap

The positive relationship between high-skilled immigration and entrepreneurial quality and quantity intensifies in regions with greater diversity in the country-of-origin of its foreign-born residents. Migrants tend to found ventures at a higher rate than non-migrants and they tend to be more successful (Kauffman Foundation, 2019). Talent that drives entrepreneurial growth tends to come from high-skilled migrants; thus, the integration of multiple migrant groups can intensify the positive effects of high-skilled migration. For example, about 12 percent of residents in the United States are migrants; these migrants are twice as likely to become entrepreneurs as native-born Americans; with first generation migrant entrepreneurs accounting for about a third of all new entrepreneurial activity in the country. Migrant business owners are also prevalent in Australia, Canada, and most countries in Europe. In their adopted countries, many migrants effectively create their own jobs, and provide goods and services that might not exist or be in limited supply (Sinkovics & Reuber, 2021). In certain industries like high-tech, migrant entrepreneurs might use their home-country knowledge to compete with their rivals in both developed and developing countries. Although migrant business owners contribute to job creation and enhancing the growth of local economies, as alien ‘others’ they often face challenges entering and participating in the local ecosystems of their host countries. Instead, their otherness could be turned into a resource base for a migrant community.

Migrants may also operate as investors, employees or leaders in MNCs. Migrants bring to host countries social networks, experience, innovation, entrepreneurial knowledge, bridges to foreign investors, among other assets and resources. Special market knowledge of migrants can enhance firms’ internationalization, advance organizational dynamic capabilities, and create novel foreign markets (Rana & Elo, 2017). Many migrant employees use their home-country experiences (human capital) to build ties with relevant stakeholders in foreign markets. The ability of migrant employees at headquarters to connect with executives at foreign subsidiaries could enable various forms of ‘innovation’ from headquarters to the subsidiaries or ‘reverse innovation’ from the subsidiaries to the MNCs.

Migration policies can have serious implications both, on the migrants and the economic growth of countries. In addition to COVID-19 restrictions on mobility, recent moratoria on a number of work-visa categories in developed countries are hindering the circulation of people and ideas in high-productivity industrial clusters, such as Silicon Valley, New York, etc. Factors such as lack of access to ‘startup visas’ or to capital create inequitable entrepreneurial environments that hinder the potential of migrant entrepreneurs. Interestingly, inclusive and welcoming policies can be a tool employed by host governments to improve their countries’ competitiveness by leveraging the economic and innovation value embedded in the lived experiences of migrants, and in their rich diversity (e.g., racial, ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation, linguistic). Migrant entrepreneurial ventures herald a more diverse and interconnected international business environment, thus highlighting the positive effects of international migration. For example, countries like Chile and Portugal use migration policies to drive economic growth.

How Can Policymakers and International Businesses Advance Equitable Inclusion of Diverse Migrants in Host Societies?

The lack of intersectional and interdisciplinary approaches results in an inadequate understanding of migration dynamics and the role various types of migrants (e.g., migrant women, ethnic and racial migrant minorities, multilingual migrants, etc.) can play as change agents and contributors to global business and entrepreneurship. This leaves firms and governments to underperform as they work on overly simplified talent programs and migration policies.

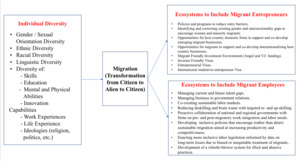

Figure 1 summarizes the main structural gaps present in host countries that hinder their ability to integrate migrants into their societies and economies. These are not mere theoretical concepts but capture the hard reality of individuals whose plight has become even more pitiful in the last few years due to immigrant-blaming and bashing policies. As noted above, the losses to host countries can be significant, and firms and governments need to work collaboratively in correcting these structural gaps. Moreover, there are significant policy concerns about the impacts of migration on social cohesion on sending and receiving sides.

Migrants represent ‘citizens’, people with valuable skills and relationships prior to their migration; after migrating they transform into ‘aliens,’ objects of institutional and policy impediments and social stigmatization. There is a growing concern that segregation, allowed through social stratification and tolerance of separate parallel lives of migrants can negatively impact the receiving society. Additionally, mismanagement of migrant talent may produce shadow markets and informal economies. Furthermore, even in countries that have fewer structural gaps in times of normality, crises and turbulence exposes new fault lines and creates circumstances where migrants might be left behind. For instance, in times of turbulence, like the recent pandemic, migrants found themselves facing the same storm again but just in a different boat (Kothari, 2021). Integrating migrants as employees and entrepreneurs in ways that optimize the value of their superdiversity will require organizations and governments in host countries to take specific actions aimed at improving labor and business ecosystems. As presented in Figure 2, we recommend policymakers and corporations create migrant inclusive ecosystems that provide equal opportunities for an alien to transform back to being a ‘citizen’ in their host country.

The key takeaways for management, policymakers and civil society are:

-

Explore the richness embedded in migrant superdiversity and employ such talent fully, creatively, and sustainably. Migrant favorable labor certification and licensing policies that acknowledge migrant’s education from their home country as a starting point makes the transition phase to the host country shorter. For instance, a migrant doctor being provided due credit for their education in the host country rather than having to start from scratch allows for them to optimally use their skills sets rather than having to drive a taxi to make ends meet. A targeted re-skilling to adapt or update required qualifications and language training can speed up talent employment.

-

Develop fair and inclusive migration policies with transparent criteria for diverse migrant workers, entrepreneurs, and investors. For example, having clear and transparent visa policies and rules for all migrants instead of discriminating based on country of origin. Migrant entrepreneurs originating from developing countries face higher requirements for business establishment and may not be able to immigrate their families.

-

Co-create local economies with all stakeholders for better social cohesion. For example, partnerships between municipalities, businesses, and non-profit organizations fostering migrants’ transitioning process, by helping them find jobs, retrain, and connect with local mentors. Such initiatives benefit the community as a whole: higher incomes, more jobs, more entrepreneurial activity, a more inclusive society.

It is difficult to find policy-oriented research that examines the superdiversity of migrants and the effects of these various diversities (and the intersectionality of these diversities) on social cohesion and economic growth. Migrant inclusion and integration in host societies is a dynamic phenomenon involving multiple dimensions and stages, and migrants’ diversity cannot be capitalized upon with one-size fits all policies. Inclusion practices need to evolve over time, to fit changing circumstances (i.e., education and labor markets, demographic changes, external shocks, digitalization, etc.). Future policy and corporate talent programs must address the superdiversity of migrants and provide integrated approaches for their inclusion in businesses and society.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the special issue editorial team whose comments and suggestions helped improve and clarify this manuscript.

About the Authors

Tanvi Kothari (tanvi.kothari@sjsu.edu) is Associate Professor, School of Global Innovation & Leadership, Lucas College and Graduate School of Business, San José State University. Dr. Kothari’s area of research interests include innovations originating in emerging markets, migrant entrepreneurship and strategic impact of new technologies on firms. She contributes as a scholar publishing in books and journals like Journal of World Business, Journal of International Management, Management International Review, Journal of Management Education etc. Her Op-Eds on diversity and migration have been published by leading media outlets and she also serves on the Editorial Board for some leading International Business Journals.

Maria Elo (melo@sam.sdu.dk) is Associate Professor of International Business & Entrepreneurship, Department of Business & Management, University of Southern Denmark. She works on internationalization, resources of skilled migrants and returnees, migrant and diaspora entrepreneurship, transnational and family business, diaspora networks, investment and remittances. She has published books and articles, for example, in Journal of World Business, Journal of International Management, Journal of International Business Policy, Industrial Marketing Management, Regional Studies and Journal of International Entrepreneurship. She is a senior editor of European Journal of International Management and a speaker at various institutions, like UNCTAD, UNECE and World Investment Forum.

Nila Wiese (nwiese@pugetsound.edu) is Professor of International Business and Marketing, and Director, Latin American Studies Program, at University of Puget Sound. Dr. Wiese’s areas of research interest include international business strategy in emerging markets, particularly Latin America, cross-cultural values, diversity issues in organizational behavior and leadership, and pedagogy. In addition to her work as a researcher, she has professional experience in banking, consulting, executive training, educational administration, and small-business development. She is a country co-investigator in the GLOBE 2020 Project, and her most recent work is an upcoming book on Business in Latin America.

.png)

.png)