Introduction

The expansion of global value chains (GVCs) is enabled by regulation, policy and trade reform across local, national, regional and global levels (Sotomayor & Cordova, 2022). Yet, regulatory interventions have not altered unequal power structures in GVCs (van Tulder & van Mil, 2022), or achieved sufficient levels of social and environmental upgrading on a global scale (Ghauri, 2022). Consequently, there is a need for inclusive governance which leaves no stakeholder behind.

The fragmented and incomplete set of markets in today’s global economy means a constant need for some form of “suasion”, obliging firms to govern themselves more effectively. Whilst stakeholder theory, institutional theory, and social cost accounting explain certain corporate social responsibility actions, these perspectives lack appreciation of the social or political will required to redress negative externalities.

Through three case studies – the success of labour organisations in setting and monitoring labour standards in GVCs, the international challenge of human development faced by South Korean firms during their upgrading in GVCs, and regulatory efforts to safeguard decent work in regional value chains of Sub-Saharan Africa – we show that the necessary condition for inclusive GVC governance is the systematic empowerment of subordinated value chain stakeholders, which can be achieved through the actions of individual key value chain actors – owners/directors, workers, managers, financiers, investment and trade negotiators, policymakers, buyers and consumers. We argue that the empowerment of the economic “South” (economies of the world not characterised as “developed”) is indivisible from inclusive GVC governance. A revived form of multilateralism built by key value chain actors across the economic North and South is central to the empowerment process. We propose a Framework for Intervention with five actions to bring about this empowerment.

Case Studies

Labour Organisations and Labour Standards in GVCs

Emerging from a major labour disaster, the Bangladesh Accord 2013, a legally binding agreement between global brands, retailers and trade unions has improved safety in hundreds of factories in the Bangladesh garment sector, through independent factory inspections, corrective action plans and monitoring of remediation actions (Croucher, Houssart, Miles, & James, 2019; James, Miles, Croucher, & Houssart, 2019). A fundamental element of the Accord is shared governance between labour and global brands. The 2013 Accord prescribed requirements for worker representation through the establishment of health and safety committees, comprised at least 50% by workers. It also required factories to establish a credible, independent complaint mechanism for workers to identify health and safety risks. In 2018, a second Bangladesh Accord was signed to extend the work of the original Accord. In 2021, global brands and global unions agreed to a third Accord. Under the renewed International Accord 2021, they committed to expanding health and safety programs beyond fire and building safety, and to developing Country-Specific Safety Programs in selected countries based on feasibility. In December 2022, it was agreed that the Accord would expand into Pakistan, offering protection to more workers.

The Better Work Program, a partnership programme between the International Labour Organisation and International Finance Corporation, seeks to improve compliance with labour standards and promote garment industry competitiveness. It has steadily improved compliance with core labour standards in garment factories across the economic South, e.g., Indonesia, Pakistan, Cambodia, Vietnam, Ethiopia and Egypt. It brings together governments, global brands, factory owners, unions and workers to improve working conditions (Miles, 2015). A distinctive feature of the Program is the involvement of labour (global union federations, trade unions and Performance Improvement Consultative Committees) in program design, implementation, monitoring and assessment. Research demonstrates clear improvements across compliance areas under the Program, enabled by collective worker voice mechanisms at the factory level (Pike, 2020).

In these examples, external stakeholders influenced the intrinsic motivations of multinational enterprises’ (MNEs’) activity. Managers and workers at the production end of supply chains were part of the solution to achieve change, leading to the empowerment of subordinated GVC participants; and initiatives contributed to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3 “Good Health and Well-being”, 5 “Gender Equality”, 8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth” and 10 “Reduced inequalities”. Importantly, civil society (through private standards, social movements and pressure groups) galvanised the social and political will to redress negative externalities.

The Republic of Korea Value Chain Upgrading Experience

Recent work (Buckley, Driffield, & Kim, 2022; Driffield, Kim, & Temouri, 2022) highlights how Korea transitioned from an emerging economy to one of the richest in the world. Its GDP per capita overtook levels found in many developed countries by 2021. Internationalisation, and a critical understanding of, and engagement with GVCs was at the heart of this. Interestingly Korean firms did not typically follow the process of seeking to move up existing value chains, in the way that one could argue firms in Taiwan or Malaysia have done, but rather sought to develop their own, simultaneously developing chains in their traditional sectors, and seeking to engage with, and then developing new ones in emerging high-tech sectors. Over three decades, Korea moved from a labour-based economy, producing mostly low-tech items such as clothing, to a leader in high-tech products, including consumer electronics and semi-conductors. Korean firms created value chains through both offshoring and outsourcing to neighbouring countries, retaining control of design and marketing in Korea, whilst moving manufacturing abroad. At the same time, resources freed up for investment at home went into high-tech activities, with firms upgrading technologically within export-oriented industrial structures with an emphasis on value-adding manufacturing. At the same time, such firms sought to augment their technology through technology-sourcing foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly to the US but also to Europe.

Kim, Driffield and Temouri (2016) detailed how Korean firms, prompted by Korea’s cost disadvantages and saturated markets, fiercely competed by expanding overseas to find new markets, acquire or improve technological advancements, or fuel their research and development. Korean firms exploited host country comparative advantages, simultaneously engaging in efficiency-seeking FDI to developing countries and technology-seeking in the West, notably into the US, with firms establishing links with US universities. These symmetrical paths of Korean-outward FDI were then mirrored by trade flows, from low-cost locations to both the home and third-party countries, facilitated by Korean market-seeking FDI that substituted exporting. The interaction between private and public governance induced FDI, trade and knowledge flows as an integrated system, and facilitated Korea’s participation in, and subsequent dominance of, certain GVCs.

Shifting South: Regional Value Chains and Governance of Decent Work in Saharan Africa

GVC analysis explains how retailers in the economic North exercised private governance over GVCs by coordinating sourcing, setting the commercial conditions and standards for suppliers based in the economic South, often interacting with public regulation. Whilst public–private governance research has focused on GVCs with Northern lead firms (e.g., Pasquali & Alford, 2022), South-South trade is now surpassing North-South trade. “Southern” lead firms are expanding within and across “Southern” regions. Southern suppliers are increasingly able to serve various chains oriented to end-markets across North and South. All these have ramifications for suppliers and workers – including how and by whom they are, and should be, governed.

Alford, Visser, and Barrientos (2021) studied the public–private governance of regional and domestic value chains (R/DVCs) in Sub-Saharan Africa. They examined South African and Kenyan agro-food suppliers serving South African and Kenyan lead firms, and South African, Lesotho and Eswatini garments suppliers selling products to South African lead firms. In both sectors, private social standards were implemented by Southern lead firms governing R/DVCs to a much lesser extent than Northern lead firms in GVCs (Pasquali & Alford, 2022; Pasquali, Krishnan, & Alford, 2021). This was compounded by a lack of public governance protection – insufficient labour legislation and regulatory enforcement by the state – for the most vulnerable smallholder farm and waged workers, employed on precarious, short-term contracts. However, they also found that both the Kenyan and South African states – in response to reputational damage and civil society pressure – had enacted value-chain-oriented policies to mitigate against private social and environmental governance deficits found in RVCs/DVCs.

A Framework for Intervention

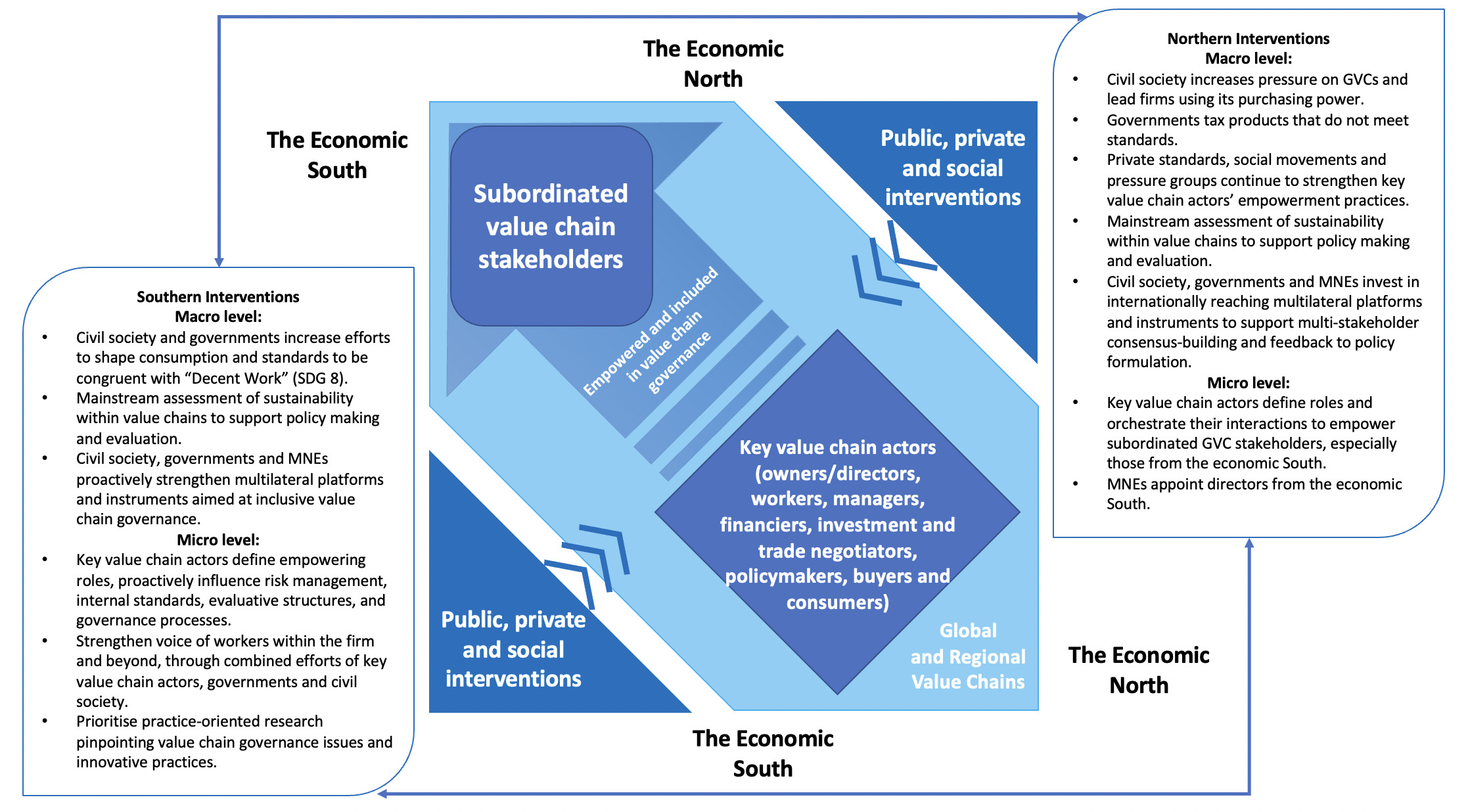

All three case studies demonstrate a need to systematically empower the weak links of GVCs, i.e., subordinated stakeholders including employees, unions, and subcontracted workforce. We propose a Framework for Intervention (Figure 1) which sets out five actions for this empowerment.

Who is involved in the empowerment process? At the centre of Figure 1, we can see that existing power structures can be mediated by the way key actors define their roles in relation to subordinated stakeholders (e.g., Cummins, 1986), especially those in Southern host economies. While individually key value chain actors (centre right of the Figure) face constraints, they have choices: they can decide how to interact with subordinated stakeholders, what messages to communicate, what goals to achieve, and what to prioritise during discourse, thus orchestrating the process for empowerment (e.g., Kern et al., 2022).

How can empowerment be achieved? In the upper right and lower left corners of the central frame of Figure 1, we can see that civil society and advocates of subordinated stakeholders can play a strategic role. Private standards, social movements and pressure groups can function as governance mechanisms when they give key value chain actors the “backdrop” of their efforts to define their empowering roles. Initiatives such as Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) standards, the United Nation’s Agenda 2030 and the Better Work Program can become resources for key value chain actors in making the (business) case for empowerment. The Bangladesh Accord demonstrates the potential of legally binding private contracts to commit global brands to observe the rights of subordinated stakeholders to improve labour conditions. These initiatives start the race among firms to meet society’s expectations for inclusion.

What interventions are necessary? First, interventions should focus on the economic South. The “Shifting South” case showed how standards congruent with SDG 8 “Decent Work & Economic Growth” were observed to a lesser extent in R/DVCs within the economic South than in GVCs governed by Northern lead firms. The Bangladesh example showed that Southern worker safety is critical to the resilience of global brands and the importance of the empowerment of workers. The Korean case, by highlighting the catch-up success of domestic firms through internationalisation and building their own value chains, raises the urgency of understanding whether and how these champions have achieved SDG 8 in their Southern host countries.

Second, interventions should leverage the purchasing power in the North and the consumption drive in the South. Governments’ taxing products failing to meet standards demanded by Northern consumers may be a solution for compliance that can cascade. But it is an option that really only exists in the economic North. As end-markets continue to shift South via expanding R/DVCs, Southern policymakers should grasp this opportunity to enforce labour standards; civil society should galvanise and leverage consumer pressure to encourage Southern lead firms to implement private social and environmental standards, thus generating support and resources for key value chain actors to orchestrate empowerment.

Third, interventions should mainstream, in policymaking, the assessment of sustainability (SDGs) within value chains. While all three cases illustrate the regulatory responsibility of nation states, the lack of a complete picture of value chain governance, coupled with a lack of attention to resolving complex sustainability issues, likely leads to policies which fail to tackle structural problems across borders. The Korean government’s policies to encourage technological upgrading, trade, and FDI transformed the Korean economy to fully developed status. But how can sustainability, including decent work, be achieved in other Southern economies that strive to move up GVCs? We think this will require (1) policymakers, in both the economic North and South, to increase demand of holistic sustainability assessment of value chains; and (2) academics to meet the demand by prioritising practice-oriented research (Nachum, Sauvant, & Van Assche, 2022) to pinpoint value chain governance issues and innovative practices.

Fourth, interventions should combine efforts at the micro and macro levels. The Bangladesh example shows how the role of advocacy and voice of workers in the workplace creates inclusive GVC governance. Giving voice to workers and appointing their representatives, particularly from the economic South, to participate in decision-making and governance, offers a way ahead. Equally important is for key value chain actors to more sharply define empowering roles, e.g., to exert influence targeted on risk management, internal standards, evaluative structures and governance processes.

Fifth, interventions should invest in building a revived form of multilateralism to bring on board key value chain actors and civil society from both the economic South and North. A “multi-stakeholder consensus-building approach” can be “effective and impactful” (Zhan, 2021: 216). The three case studies demonstrate the interconnectedness between the economic North and South, the limits of “local” solutions (also see Scherer & Palazzo, 2011), and the promise of cross-locational interventions. The type of multilateral platforms and instruments needed should, at a minimum, have these functions: (1) enable the involvement of subordinated GVC stakeholders, civil society, and key private and public value chain actors; (2) support key value chain actors to define their empowering roles; and (3) mainstream the use of good practices of inclusive governance in policy research and formulation. Civil society, governments and MNEs from the economic North should take a lead in investing in multilateral platforms and instruments, whilst counterparts in the economic South focus on strengthening them.

Conclusion

To summarise, our discussion highlights the necessity of interventions at the level of civil society and by key private and public value chain actors in creating inclusive governance of GVCs. We argue that interventions should be aimed at empowering the economic “South” and fundamentally focus on human development. As part of this we argue that the power of GVCs needs to be harnessed, with an understanding that engagement with GVCs is how many firms internationalise, and subsequently upgrade their technology and productivity. To achieve this, we argue for a combination of micro and macro initiatives and a revived form of multilateralism, with the support of platforms and instruments to mainstream the collaborative creation of power to build inclusive GVC governance. Promising progress is underway. The WTO Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development is poised to promote a multilateral framework, with “facilitating greater developing and least-developed Members’ participation in global investment flows” as its core objective (WTO, 2021). Through this AIB Insights publication, we call for more future interventions to be underpinned by a precise focus on human development and rigorous policy research geared towards crafting the instruments needed to deliver it.

Data Access Statement

No data are associated with this article.

Acknowledgements

This paper is developed following a special panel entitled “What does it take to build an inclusive governance of global GVCs?” organized by the Mainstreaming Impact in International Business (MIIB) initiative during the UK & Ireland AIB Annual Conference on April 9, 2022. We thank the audience from the conference and online for their thoughtful comments and feedback.

For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

About the Authors

Elizabeth Yi Wang is Associated Professor of International Business at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom. Her research focuses on firm internationalisation and the interaction between international business, international business policy and sustainable development. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, a recipient of the Women of Achievement Award, and the founder of the Mainstreaming Impact in International Business Initiative. She has been invited to advise overseas institutions on strategic issues such as regional development and education.

Nigel Driffield is Deputy Pro Vice Chancellor for regional engagement and also Professor of International Business at Warwick Business School, having held a similar post at Aston Business School for 10 years which included a spell as the dean of the business school. He has a PhD from Reading University, and has published some 80 academic papers across a range of disciplines including international business, regional science, finance, and economics.

Jeremy Clegg is Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration & International Business Management at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom. He is an area editor of the Journal of International Business Policy and has served as a member of the editorial review board of the Journal of International Business Studies. His research, employing both quantitative and qualitative methods, has encompassed a broad range of areas within mainstream International Business. He is a past president of the Academy of International Business.

Lilian Miles is Reader in Sustainability and Social Enterprise at the Westminster Business School. Her research focuses on how change can be achieved in ways which benefit workers and which secure their rights and livelihoods. She has published widely on worker empowerment and capability. She has extensive experience working with a range of global partners and agencies, from UN organisations, government, third sector organisations, trade unions, healthcare professionals and industry actors.

Matthew Alford is Associate Professor at the University of Manchester. His research explores the role of nation states in governing labour and the environment, and how public regulations interact with private codes of conduct and civil society initiatives across geographical scales. He has published in Journal of Economic Geography, Review of International Political Economy, World Development and Journal of International Business Policy. He is on the organizing committee of Network O (Global Value Chains) within the Society for Advanced Socio-Economics.

Jae-Yeon Kim is Assistant Professor of International Business at the University of Portsmouth. His research explores the role of outward FDI in creating global value chains (GVCs) and how the economic development features of home and host countries affect firms’ FDI location choice by motive and industry. He has participated in several research programmes related to regional development in the United Kingdom. He has published in Management International Review, Journal of Business Review and International Journal of Multinational Corporation Strategy.