Introduction

When Russian forces invaded Ukraine in 2022, multinational enterprises (MNEs) from Europe and North America faced intense pressures to disassociate themselves from Russia, and its political leadership. Many had invested over two decades to build local market share in the world’s eleventh largest economy, to develop local supply chains or to tap into Russia’s resource and mineral wealth. Now they faced complex ethical dilemmas. Public opinion has been leaning very strongly on them to disengage completely, yet they also had legal and moral obligations within Russia, for example with respect to their own employees.

This situation in Russia represents a particularly severe case of political disruption to international business, which can also include military coups, violent unrest, wars and economic sanctions. Political disruptions may start as single country events but are often amplified by the interplay of politics in home and host countries. International Business scholars such as Witt (2019) and Hartmann and Devinney (2020) argue that such disruptions are likely to occur frequently in the near future. They can affect MNEs at multiple levels:

-

Operationally, MNEs’ supply chains may be disrupted by new barriers to trade, labor and capital flows, by dislocated transport linkages, or even through physical damage to facilities from military actions.

-

Financially, MNEs may face an immediate drop in the value of their assets in the affected country due to lower revenues or increased costs. They may also be unable to repatriate profits or to continue to fund operations externally.

-

Strategically, MNEs may have to reassess the focus of their growth strategies, and the optimal geographic configuration of their value chains.

-

Ethically, MNEs may have to reassess doing business in countries where operations or business partners can no longer satisfy the MNEs’ aspired corporate social responsibility standards and values.

When facing political disruptions, the challenges for MNEs within the host country may be compounded by a variety of stakeholder pressures to disengage (Mol, Rabbiosi, & Santangelo, 2023). How can MNEs navigate this financial and ethical complexity? Perhaps surprisingly, many firms that disengaged from Russia in early 2022 performed better on the stock markets than those who stayed (Economist, 2022). At the same time, very few companies fully divested operations in the country (Evenett & Pisani, 2023). Why should firms disengage from a country facing political disruption? MNE motives for disengagement includes financial and ethical considerations (Exhibit 1). These higher-level objectives influence not only the decision whether to exit, but also the design of the exit strategy.

Exit Decision Process

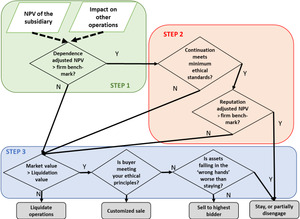

We suggest that MNEs facing pressures to exit due to political disruptions should organize their decision process in three steps: First, to clarify the financial implications considering the implications of disengagement for operations outside the focal country. Second, to assess the ethical implications of continuing operations in the country. Third, if they opt to disengage, to assess the merits of alternative disengagement strategies, including partial and full exit. Exhibit 2 summarizes our arguments in the form of a decision tree.

Step 1: Evaluate the financial impact of possible disengagement, including interdependence of global operations

Let’s start our analysis from conventional financial analysis. A political disruption potentially affects the revenues, costs and risks of an operation (De Villa, 2023; Meyer, Fang, Panibratov, Peng, & Gaur, 2023), and thereby influences (usually reduces) decision parameters such as net present value (NPV). The financial analysis however cannot be limited to the operations in one country alone. Because of their global reach, MNEs tend to have integrated operations, so discontinuation of activities in one country may disrupt operations elsewhere.

A resource-dependency analysis is particularly helpful to evaluate these considerations. The dependence of the parent firm on the subsidiary can arise for example when the latter provides critical raw materials or intermediate products. In this case, the entire parent operation may be undermined by an abrupt exit. Examples include intermediate products in complex value chains or raw materials such as oil, gas, nickel, palladium, etc. Dependence of the subsidiary on the parent arises in particular from ongoing and difficult to substitute inputs from the parent, such as high-tech components. In such subsidiaries, cutting off international supplies would be effective in stopping the operation.

Exhibit 3 brings these considerations together. In cell 1, the parent is highly dependent on the subsidiary, and an exit would substantially harm the global company. This situation may arise for subsidiaries that are the sole supplier of certain raw materials or intermediate goods. For example, Danish building materials producer Rockwool has its technologically most advanced facility in Russia supplying operations across Europe, and thus was resisting pressures to divest (Rosenqvist, 2022). Cell 2 includes operations that are highly integrated within both the global company and the local economy. In these cases, an assessment of the relative harm is very complex.

Cell 3 includes subsidiaries that operate with a high degree of operational independence with few critical international trade flows. Some Western MNEs had successfully built operations in Russia to locally deliver goods or services that do not substantially depend on exports or imports. This includes US restaurant chains such as McDonalds and Burger King, retailers such as Auchan (France), brewers such as AB Inbev (Belgium) and Carlsberg (Denmark), as well as consumer goods companies such as Danone (France) (Jack, Morris, White, & Edgecliffe-Johnson, 2022; Lehto & Kauranen, 2022). The foreign owners invested heavily in capability building and brands, but the businesses could substantially could be run by local owners without regular interactions with foreign partners. Under these conditions, a sale of the business operation is comparatively straightforward because the need for post-acquisition restructuring is modest. However, also nationalization and continuation of the operation is feasible, giving the host government pressure points in the negotiations.

Finally, cell 4 includes subsidiaries that are highly dependent on the parent, for example, assembly lines for machine tool and car manufacturers that are critically dependent on imported components such as engines or electronics that are not locally available. In Russia, European car makers such as Mercedes or Stellantis fall in this category. Their local operations can be disrupted by stopping exports of these components, which makes them ideal targets for economic sanctions.

Step 2: Assess the ethical arguments for and against disengagement

Political disruptions may also confront MNEs with ethical issues potentially affecting their global reputation. Ethical arguments to leave a foreign location usually focus on the association with a government that pursues policies in violation of generally accepted international norms of international relations and in contradiction to the firm’s own corporate values, such as human rights violations or military activities in other countries. A classic example is the disengagement of many Western MNEs from South Africa during apartheid.

Such ethical issues may result in pressures from a variety of stakeholders. For example, civil society groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) may target companies engaged in particular host economies because of human rights abuses; major shareholders such as pension funds may regard investments in certain locations or sectors as being in violation of their own ethics codes; while governmental stakeholders may wish to limit investment in some countries for political or military reasons. The relevance of these arguments varies substantially with the type of operation the MNE conducts in the country, but the pressures will be stronger, the more the MNEs’ operations in a country provide resources that are – or could be – used for the objectionable activities. For example, technology might be used directly or indirectly for military purposes or to pursue human rights abuses. Stakeholders may also argue that a company’s activities indirectly support the host governments via tax revenues.

The ethical analysis also has to consider risks of deteriorating local conditions that may lead the company on a slippery slope that eventually lead to unethical activities in its subsidiaries. For example, Lafarge of France decided to continue operating its cement factory in Jalabiya, Syria when the civil war spread, considering both the high sunk costs incurred during the construction of the plant and expected opportunities in the post-war reconstruction of the country. However, as the civil war accelerated, Lafarge managers ended paying groups considered terrorists by Western government to secure passage for employees, and later failed to protect the safety of its employees when evacuating the plant. Penalties for corrupt practices followed in both US and French courts (Alderman, Peltier, & Saad, 2018; Waldie, 2018).

However, other ethical arguments may support staying in the country. A major element of corporate social responsibility concerns the treatment of employees in a company’s own operations and suppliers around the world. Laying employees off as a consequence of actions of their government over which they have often little influence may be ethically problematic. Moreover, the company may be supporting disadvantaged groups in the country, for example by providing for basic needs or critical health care.[1] In addition, certain assets controlled by the MNE may cause greater harm in the hands of the host government or its associates. For example, when Norwegian telecom operator Telenor responded to pressures from civil rights groups to divest from Myanmar after the coup of 2020, it faced a different set of pressures not to divest because of concerns that the new owners would provide the government access to personal data of mobile phone users, with negative consequences for opposition activists (Purdon & Phonsathorn, 2021; Wallace & Liu, 2021).

The relative importance of ethical considerations varies for different firms, depending on the type of their operations in the target country and the influence of the relevant stakeholders. For example, companies with highly visible consumer brands are more exposed to stakeholder activism and consumer boycotts while listed firms are subject to more public scrutiny than privately held companies (Meyer & Thein, 2014).

The ethical arguments may be integrated with the financial arguments in two ways (Exhibit 2). First, if continuation would lead to a violation of its minimum standards of corporate values, then the company has to withdraw (or rewrite its ‘values’ statement). Second, if continuation meets minimum standards but still creates ethical challenges and risks, these may be incorporated in the decision making by reducing the NPV.

Step 3: Assess different formats of disengagement to ensure consistency with higher level ethical objectives

Once a decision to exit a foreign country has been reached, the next question is how to exit? On this question, we have virtually no literature in IB. While a substantive literature analyzes subsidiary exit versus survival, very few studies differentiate types of exit (Dai, Eden, & Beamish, 2022). Conceptually, we can distinguish full disengagement or partial disengagement, such as the freezing of operations. The decision-making is complicated by the fact that the identity of the future owner matters for the achievement of ethical objectives.

Partial disengagement presents lower financial risk for the company (Exhibit 4, Panel A). Thus, for example many businesses in Western Europe announced a “freeze” on their operations in Russia, which essentially means that they would not undertake new resource commitments to the country. In the short run, such ‘freezing’ has little effect on the subsidiary operations but by restricting modernization of facilities or marketing campaigns, it may erode competitiveness. However, such actions may alienate local stakeholders while being unlikely to satisfy engaged stakeholders in the home country.

Companies may also engage in what Meyer and Thein (2014) in their study of Myanmar called low-profile strategies. These strategies reduce resources in the country, especially those visible to outside observers, but maintain at least a foothold in the country. Low profile strategies of partial disengagement may take many different forms, including:

-

stop selling international brands, but continue operating using local brands only,

-

stop selling products branded ‘made in’ the country of concern,

-

replacing a sales subsidiary by legally-independent distributors,

-

reducing equity stake in joint ventures,

-

selling a business unit and then licensing to it to enable continued operations (i.e. the operations are outside the formal ‘boundaries of the firm’ but still under de facto control),

-

stop supplies of intermediate products and technology to a subsidiary such as to disable operations without giving up legal titles.

However, these strategies may also not satisfy the relevant stakeholders. Thus, even investors with long-standing operations in Russia have been contemplating more complete withdrawals. Yet, several practical obstacles arise when trying to divest after a political disruption. Primarily, after political disruptions, buyers for corporate assets are in short supply. In principle, the businesses could be sold to local investors or to investors from third countries that did not impose sanctions (Meyer et al., 2023). For example, McDonalds sold its Russian business to a local business partner who continued operating the restaurant chain under a new name (Astrasheuskaya, 2022). Yet, with the absence of potential Western buyers, increased political risks, and potential logistical challenges, the sales value would likely be substantially below the pre-sanction valuations.

Moreover, selling assets to local businesspersons at a discount would transfer major value to local elites likely associated with the political leadership of the country. Such new owners would likely manage the assets according to their own values, which may support the government yet pay little attention to social responsibility towards employees and other stakeholders of the exiting MNE. Reports of Russian business tycoons such as Vladimir Potanin building powerful business empires through acquisitions of exiting foreign owners support this concern (Astrasheuskaya & Hume, 2022). Even then, valuation and drawing up contracts may be inhibited by a thin and non-transparent market for corporate assets in politically unstable environments, and a shortage of investment bankers with relevant M&A experience (Lehto & Kauranen, 2022).

We summarize the options for a complete divestment in Exhibit 4, Panel B. The MNEs could, theoretically, exit by disabling the functionality of operations (temporary or permanently), locking up the factory, or burning the facility – which is risky due to likely retaliatory actions. Apart from operations at the frontline of a military conflict, such radical exit is rare. Alternatively, if the focus was entirely financial, the MNE could sell the assets to the highest bidder, though possibly at a price much below the pre-disruption price. Potential buyers would include local businesspersons, private equity less exposed to civil society stakeholder pressure, or third country investors that do not face the same stakeholder pressures to disengage.

Full disengagement might also be subject to the same ethical considerations that led to the decision to disengage. Hence, MNEs should sell to a buyer acceptable from an ethical perspective, i.e. a buyer who will not use the assets contrary to the values of the MNE and its stakeholders. Thus, buyer due diligence would exclude, for example, cronies of the government or companies involved in human rights abuses. Buyers qualifying under these considerations could be existing business partners or the existing management team. Such a trusted buyer may be willing – with suitable financial inducements – to adopt social obligations. A sale to a trusted partner may also contain a buy back clause. Reportedly, McDonalds and Renault have sold their assets to local partners with such a clause in their contracts (Lehto & Kauranen, 2022). However, such conditions in a sales contract may be hard to enforce in an authoritarian or otherwise volatile country.

Conclusion

Recent cases from Syria 2014, Myanmar 2020 and Russia 2021 show a wide variety of corporate responses to home country pressures to divest after a political disruption. This variation arises from different assessments along the three steps we suggest should guide exit decisions, namely financial and ethical analysis, along with consideration of specific options for reducing commitments in a country. Exhibit 2 summarizes the arguments in a simplified decision tree that may serve as a starting point for corporate decision making. For managers, it is important to conduct all three steps carefully rather than being guided by demands from the most outspoken stakeholders. For business scholars, political disruptions open a wide new area for research.

Acknowledgements

The authors have benefited from comments from reviewers and the editor, as well as discussions with Daniel Shapiro and participants in our EMBA and Executive classrooms. Any remaining errors are their own.

About the Authors

Klaus Meyer is a Professor of International Business and William G. Davis Chair in International Trade at Ivey Business School, London, Canada. He is a Fellow of the AIB, and recipient of the 2015 JIBS Decade Award. He served as Vice President of the AIB (2012-2015) and as JIBS area editor (2016-2022). His research focuses on multinational enterprises in emerging economies.

Saul Estrin was the founding Head of the Department of Management at London School of Economics and formerly Professor of Economics and Associate Dean at London Business School. He researches in international business and entrepreneurship, especially with reference to emerging economies. He is former President of the European Association for Comparative Economic Systems and a Fellow of the Academy of International Business.

A concern raised for example by French supermarket chain Auchan in Russia (Le Monde, 2022).