Introduction

According to Ghauri, Strange and Cooke (2021), the global business environment has improved awareness of sustainability as a ‘new reality’. Furthermore, addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a corporate context is becoming increasingly popular (Liou & Rao-Nicholson, 2021; Montiel, Cuervo-Cazurra, Park, Antolín-López, & Husted, 2021; van Tulder, Rodrigues, Mirza, & Sexsmith, 2021). Although “sustainable” and “green” global mobility are widely discussed concepts, they have not yet been widely integrated into sustainable expatriate management.

However, due to its nature, expatriate management is exposed to various societal and environmental issues that are forcing the field to move towards more sustainability-oriented practices. This implies that decision- and policy-makers should revisit the overall global philosophy, including policies and practices. Therefore, stakeholders should reevaluate topics like business trip policies, health, and equality, as well as other facets of the international assignment cycle (Fan, Zhu, Huang, & Kumar, 2021). Consequently, in this paper, we will outline how practitioners can rethink expatriate management using a sustainable development lens and how this shift in perspective provides fertile ground to redesign the expatriate life cycle.

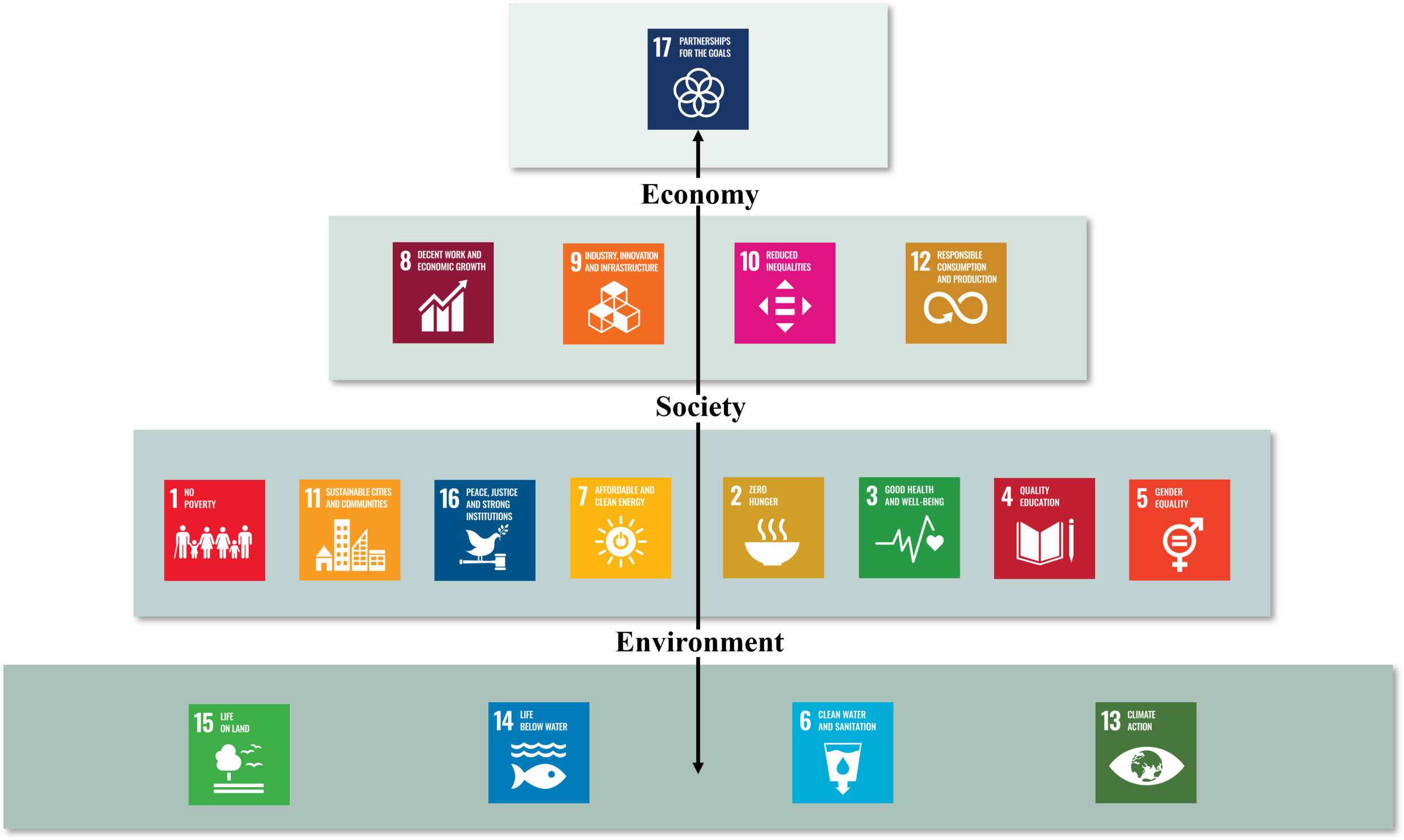

Inspired by the “strong sustainability” or embedded systems view (Giddings, Hopwood, & O’Brien, 2002), we define sustainable expatriate management as any employee-related cross-border (work) activity, which, by its design, considers planetary and societal boundaries and acknowledges the embeddedness of economic impacts within this larger framework (see Figure 1 for clarification).

Figure 1.Sustainable expatriate management

Source: Own illustration based on Giddings et al. (2002), p. 192.

Theoretical Framework: Sustainable Development Goals

According to Finaccord’s (2019) latest research, in 2017, there were 66.2 million expatriates working abroad globally, and forecasts for 2021 expect 87.5 million in total. Therefore, this topic affects a relatively large amount of people moving across borders. Nowadays, increasing environmental, social, and economic crises are challenging global business practices. According to the World Economic Forum Global Risks Report, the risks that are most likely and will have the most impact are predominantly environmental risks (e.g., climate action failure, human environmental damage, biodiversity loss, natural degradation, extreme weather, natural resources crises) (World Economic Forum, 2022). These are expected to affect multinational enterprises’ (MNEs) activities on a global scale.

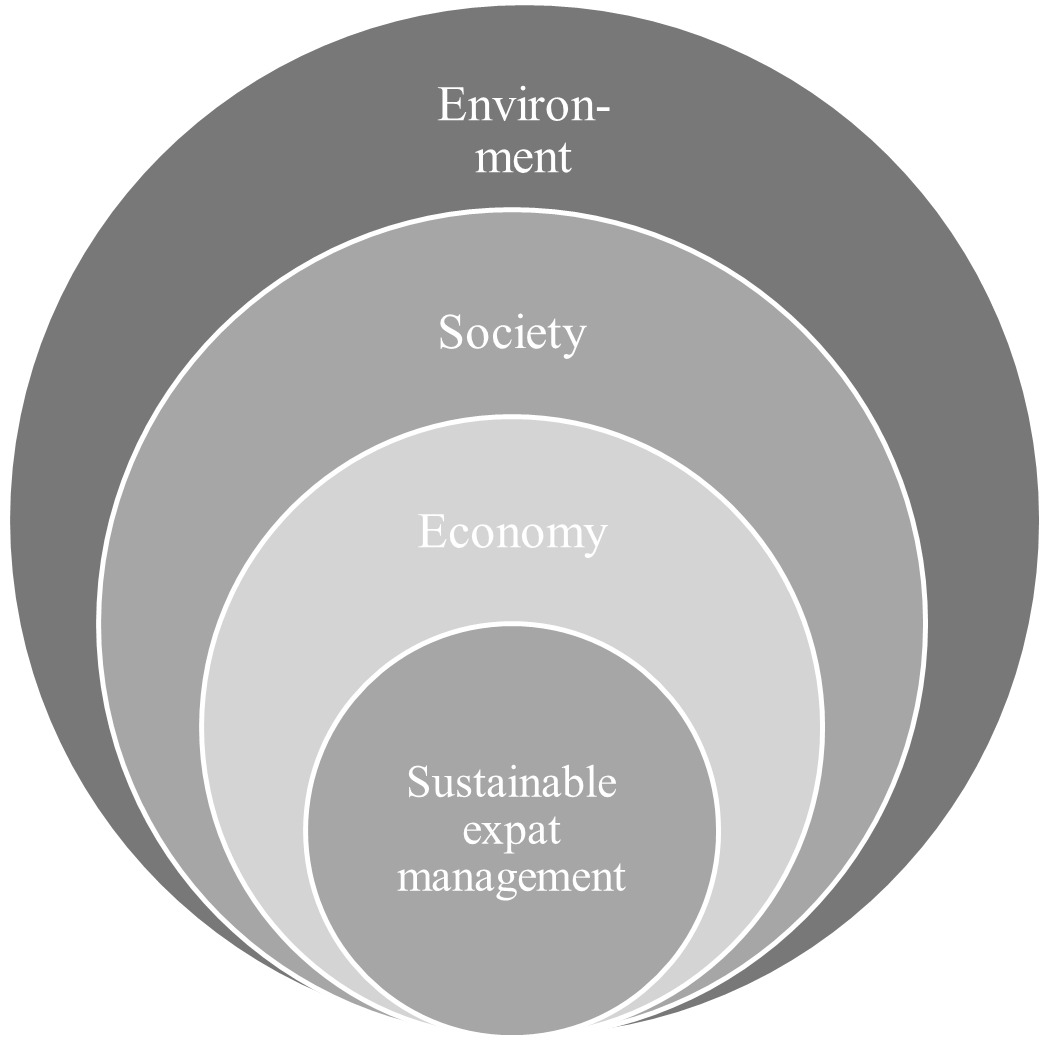

As the complex, or so-called wicked, problems of our time are interconnected, it is crucial to avoid a siloed perspective of these risk categories. Therefore, we provide a holistic, SDG-focused perspective that addresses the question of how MNEs’ business practices need to be remodeled to become more resilient. We view business sustainability in terms of environmental, social, and economic systems and consequently apply the UN Sustainable Development Goals “wedding cake” framework (Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2018). This model implies that the environmental, social, and economic layers are interdependent, as well as their respective sublevel SDGs, as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.SDG wedding cake

Based on Figure 2, the biosphere/environment represents the foundation of economies and societies and, therefore, the general context in which all other SDGs must be placed. Society cannot survive without the environment, which is why society must pay attention to resources and the preservation of habitats. Such a conceptualization adopts an integrated and interconnected view of social, economic, and ecological development to ensure the future viability of the planet and its living species.

Three Layers of Sustainability in Expatriate Management: Identifying Blind Spots

Based on a systematic literature review of 238 articles clustered according to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and their respective layers, environment/biosphere, society, and economy, it is evident that research in this field has been increasing in recent years. Furthermore, it shows that the expatriate management literature is dominated by social issues (80%), followed by economic literature (19%), and work that focuses on the environment/biosphere (1%) (Ommen, Schmitz, & Karlshaus, 2022). Considering that expatriate management is a part of international HRM literature, it is unsurprising that the social category dominates; however given the growing importance of the climate crisis discourse, it is surprising that this has not yet been addressed in research and practice.

This social literature is dominated by articles addressing SDG 5 “Gender Equality” and SDG 3 “Good Health and Well-being” as well as limited literature focused on SDG 16 “Peace, Justice, Strong Institutions”. In the economic category, the literature most often addresses SDG 10 “Reduced Inequalities” and SDG 8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth”, followed by SDG 17 “Partnership for the Goals” as an overarching category. Finally, the ecological category is only represented in one article addressing SDG 13 “Climate Action”, which has only recently been published (Ommen et al., 2022) (see Table 1 for an overview).

Table 1.Blind spots in sustainable expatriate management

| Layer |

SDG |

Expatriate management component and issues |

Selected associated references |

Blind spots |

| Economic aspects |

SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth |

Labor unions; human rights;

employee voice;

precarity and compliance |

Chang & Cooke, 2018; Wilkinson et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020; Alamgir & Alakavuklar, 2020; Bailey, 2021 |

--* (indicator rather macro-level oriented and targets less privileged environments) |

|

SDG 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure |

|

NA |

--* (indicator rather macro-level oriented) |

|

SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities |

Compensation inequalities between expatriates and locals;

LGBTQIA+ expatriates;

identity and openly voicing sexual orientation |

Toh & Denisi, 2005; van Bakel, 2019; McPhail, McNulty & Hutchings, 2016 |

Inclusive expatriate policies |

|

SDG 12 Responsible Consumption and Production |

Reducing packaging material, sustainable housing, furnished apartments |

NA |

Waste management/circular economy of goods used by expatriates |

| Societal aspects |

SDG 1 No Poverty |

|

NA |

--* (expatriates constitute a relatively privileged cohort) |

|

SDG 2 Zero Hunger |

|

NA |

--* (expatriates constitute a relatively privileged cohort) |

|

SDG 3 Health and Well-being |

Pollution and health hazards;

expatriate (mal)adjustment, alcohol and drug abuse, other physical and mental health issues |

Dickmann & Bader, 2020 |

Focus on how to foster health among expatriates and their families |

|

SDG 4 Quality Education |

|

NA |

--* (expatriates constitute a relatively privileged cohort) |

|

SDG 5 Gender equality |

Expatriate staffing gender gap;

identity constraints, bias in selection for assignments and promotion, inequitable gender power relations, a lack of organizational support;

selection bias;

gender discrimination; gender pay gap |

McNulty & Hutchings, 2016; Kirk, 2019; Ng & Sears, 2017; Bader et al., 2018; Fischlmayr and Puchmüller, 2016 |

Sensitizing staff to gender mainstreaming |

|

SDG 7 Affordable and Clean Energy |

|

NA |

--* (indicator rather macro-level oriented) |

|

SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities |

|

NA |

--* (indicator rather macro-level oriented) |

|

SDG 16 Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

Business ethics; whistleblowing; bribery; Danger; crime; terrorism; hostile environments |

Bullough & Renko, 2017; Faeth & Kittler, 2017; McPhail & McNulty, 2015; Pinto et al., 2017; Stoermer et al., 2017; Bhanugopan & Fish, 2008; Bader et al., 2019; Bader & Berg, 2013; Giorgi et al., 2016; Dickmann & Watson, 2017; Faeth & Kittler, 2020; Fee et al., 2019; Gannon & Paraskevas, 2019; Posthuma et al., 2019; Greppin et al., 2017 |

Fostering a justice-based workspace |

| Environmental aspects |

SDG 6 Clean Water and Sanitation |

|

NA |

--* (expatriates constitute a relatively privileged cohort) |

|

SDG 13 Climate Action |

GHG emissions related to business travel and relocation; mindset of travelers; virtual assignments |

Walsh et al., 2021

Lirio, 2014

Bücker et al., 2020 |

Policies on traveling/relocation recommendations; environmental nudging |

|

SDG 14 Life below Water |

|

NA |

--* (indicator rather macro-level oriented) |

|

SDG 15 Life on Land |

|

NA |

--* (indicator rather macro-level oriented) |

Source: Own illustration; for a full list of references, see Ommen et al., 2022, and the Appendix to the article.

*“–” indicates SDG cases for which blind spots were not identified in this study

What Is Material for Sustainability in Expatriate Management?

In the sustainability reporting discourse, understanding materiality (i.e., identifying elements of utmost importance to a company’s sustainability challenges) has become increasingly important as part of the international ESG factors: environment, society, and governance. Furthermore, organizations attribute different levels of importance to specific environmental or social factors based on the sectors they operate in.

Considering the essential or material topics, MNEs need to first reduce or avoid their negative impacts (e.g., CO2 emissions etc.) and also increase their positive impacts (e.g., fostering intercultural ties). By doing so, MNEs can significantly reduce the respective risks to which they are exposed.

The emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) is among expatriate management’s negative material environmental impacts, due to flights, shipments, hotel stays, and local transportation (SDG 13). These also include water and land use due to construction activities (SDG 6, 15), and waste management that should be reconsidered from an environmental perspective.

From a social perspective, negative impacts on equal opportunities can be caused by disparities in pay and promotion opportunities (SDG 5), working conditions, and health issues related to increasing travel activities and continuous readjustment (SDG 3). Furthermore, expatriates working in hostile environments or dangerous locations need adequate protection mechanisms and respective codes of conduct (SDG 16). Finally, integration into local communities during long-term stays might become relevant for some expatriates and their families (SDG 11).

From an economic perspective, a positive impact could be generated by supporting the local economy (SDG 8). However, negative impacts can arise through unequal opportunities because of the different treatment of expatriates and locals (SDG 10). To reduce this, companies should ensure responsible local consumption and circular use of respective household appliances or furniture in apartments (SDG 12).

In sum, MNEs should consider the following Sustainable Development Goals to reduce their negative impact and increase their positive impact:

-

Environmental: SDG 13 Climate Action

-

Social: SDG 3 Good Health and Well-being, SDG 5 Gender Equality, SDG 16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities

-

Economic: SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities, SDG 12 Responsible Consumption and Production

Sustainable Expatriate Management: Actionable Recommendations

The above discussion suggests that companies can derive a specific prioritized agenda. Inspired by the SDG Compass (Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact, & WBCSD, 2015), we advance these considerations by sharing how MNEs can best address the SDGs in sustainable expatriate management. For an overview of selected ideas for each of the SDGs, please also see Table 2.

Table 2.Selected SDG-related indicators/themes and questions for companies

| Layer |

SDG |

Indicator component/theme |

Questions for companies |

| Economic aspects |

SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth |

Labor practices in the supply chain |

How do expatriates ensure that labor practices, freedom of association/collective bargaining, and fair labor/management relations for marginalized and disadvantaged groups/individuals are respected? |

|

|

Freedom of association and collective bargaining |

|

|

Labor/management relations |

|

SDG 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure |

Research and development |

How can expatriates drive R&D regarding products and services which benefit the bottom of the pyramid or increase the average standard of operation across the industry? |

|

|

Expenditure and investment and intellectual property |

|

SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities |

Non-discrimination |

How can companies ensure that there is no workplace violence and harassment or any other form of discrimination between expatriates and locals?

How can companies develop local HCNs for local management positions, instead of using expatriates? |

|

|

Diversity and equal opportunities |

|

SDG 12 Responsible Consumption and Production |

Resource efficiency |

How can companies establish a circular economy approach across the expatriate life cycle? |

|

|

Waste and materials recycling |

How can companies reduce waste and increase material recycling along the expatriate cycle (e.g., apartment furniture, household appliances etc.) |

| Societal aspects |

SDG 1 No Poverty |

Access to financial services, electricity, and land |

How can expatriates ensure that marginalized groups/individuals/smallholders and other stakeholders have access to financial services, electricity, and land? |

|

|

Economic inclusion |

How can expatriates create policies and practices that promote economic inclusion when selecting suppliers for the local business? |

|

|

Availability of products and services for those on low incomes |

How can expatriates consider needs-based affordability when making pricing decisions for products targeted at the poorest population segments in relevant countries? |

|

|

Earnings, wages, and benefits |

How can expatriates shape mechanism/policy/code that seeks to ensure that small-scale suppliers, smallholders, and/or distributors are paid fair prices for goods and services? |

|

SDG 2 Zero Hunger |

Healthy and affordable food |

How can expatriates ensure that disadvantaged stakeholders or individuals have adequate access to healthy and affordable food or benefit from inclusive supply chains? |

|

|

Inclusive supply chain |

|

SDG 3 Health and Well-being |

Occupational health and safety |

How can companies ensure that expatriates benefit from adequate relocation/adjustment processes and services to improve work-life balance? |

|

|

Access to quality essential health care services and benefits |

|

SDG 4 Quality Education |

Childcare services and benefits |

Which benefits do expatriates need access to to take full advantage of training and education opportunities? |

|

|

Employee training and education |

|

SDG 5 Gender Equality |

Women in leadership |

Which mechanisms, benefits, and policies do female expatriates need to be empowered and take certain responsibilities? |

|

|

Parental leave and work-life balance |

|

|

Equal remuneration and benefits |

|

SDG 7 Affordable and Clean Energy |

Renewable energy and energy efficiency |

How do certain facilities offered to expatriates need to be equipped to meet clean energy demands? Which measures and incentives do expatriates need to be made aware of? |

|

|

Energy consumption |

|

SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities |

Inclusive business and cultural heritage |

How can expatriates ensure that disadvantaged stakeholders can access public spaces? How can they create inclusive business cultures that respect cultural heritage? |

|

|

Sustainable buildings and access to public spaces |

|

SDG 16 Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

Ethical and lawful behavior |

Grievance mechanisms, security, abolition of child labor, anti-corruption, compliance with laws and regulations |

|

|

Inclusive decision making |

|

|

Effective, accountable, and transparent governance |

| Environmental aspects |

SDG 6 Clean Water and Sanitation |

External impact management and communication |

How can expatriates use water resources more responsibly? How can MNEs foster a respectful dialogue about resource use with affected communities? |

|

|

Water recycling and reuse, water withdrawals |

|

SDG 13 Climate Action |

GHG emissions and intensity |

How can companies create nudging mechanisms to ensure that expatriates contribute to reducing GHG emissions? Which policies and travel/relocation guidelines need to be established?

How can companies find alternatives towards GHG intensive expatriate assignments, like using virtual assignments or develop local HCNs for respective positions? |

|

|

GHG reduction |

|

SDG 14 Life below Water |

Ocean acidification |

How can companies reduce their cross-border activities’ impact on marine ecosystems? |

|

|

Marine biodiversity |

|

SDG 15 Life on Land |

Impact on biodiversity and habitat |

How can companies reduce their cross-border activities’ impact on habitat degradation? |

|

|

Forest and natural habitat degradation |

Source: Own illustration; based on selected measures of the SDG Compass Business Indicators;

Note: Not all themes will apply to all types of MNEs or all sectors equally. As expatriates are usually relatively privileged, we suggest that they should use their privileged status to support disadvantaged groups and individuals to meet SDGs.

Defining Priorities

First, each of the material topics needs to be evaluated for each company. Certain topics may be more or less relevant in a corporate context, depending on the respective sector. Taking the example of GHG emissions (SDG 13), most emissions come from consultants on regular short-term assignments or business commuting trips if the company is in the service delivery sector. Therefore, these emissions play a more significant role for the company.

In terms of gender equality (SDG 5), a company should first investigate the share of women in their overall assignee population, including management positions. Based on a materiality matrix approach, respective stakeholders should evaluate their priorities alongside considering the judgment of material topics to attain a holistic perspective. By taking this approach for all topics associated with each SDG, MNEs can prioritize different materiality topics.

Setting Strategic Goals

To transform international assignments at the company level, MNEs need strategic concepts, including tools, to impact the defined materiality topics discussed above. There are different levers available to create change, including international assignment policy, processes, and culture. A policy can be designed so that assignees are nudged to not take air shipments, which cause significant GHG emissions (SDG 13). Further, by working with stakeholders across the supply chain, MNEs should implement key performance indicators (KPIs) to reduce negative impacts. To be effective, these should align with scientific facts and goals, such as the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting warming to 1.5°C.

Integrating the Goals

After defining their strategy and goals, MNEs should next address their implementation needs. This should particularly consider the sustainable consumption of mobility-related benefits (SDG 12), where there may need to be a mindset shift. Therefore, in the preparation phase, assignees need to be made aware of their choices. To do this effectively, departments taking care of international assignments may need to be trained on related topics while they consult assignees. Besides policy changes, MNEs should also implement profound changes, for example in terms of gender equality (SDG 5). Managers should be aware of equal selection principles and provide women with support mechanisms to ensure equity if they become the main caregiver for their children.

Measuring and Evaluating

Finally, MNEs need to track whether the implemented measures have been effective. This means measuring an international assignment program’s GHG emissions (SDG 13), environmental impact, gender share (SDG 5), and other measures. If the result does not meet the initial targets, the previous phases (strategy development, implementation) should be analyzed to see if adjustments are necessary. To better integrate the respective measurement indicators with those already existing in the corporate context, the SDG Compass website provides respective input categorized by SDG: https://sdgcompass.org/business-indicators/.

Conclusion

Although there is awareness of pressing contemporary challenges in the field of expatriate management, action is still needed to decrease the negative impact on society, the economy, and the environment. Many concepts aim to address sustainability across borders. However, research has not yet produced a hands-on and integrated SDG framework for expatriate management. In this work, we aim to inspire and motivate practitioners to take action and further their sustainability ambitions. Although our paper is labeled rethinking expatriate management, the challenges outlined equally apply to inpatriates, repatriates, and other forms of cross-border assignments.

Companies need to be more aware of the environmental and social impacts of their programs and need to monitor processes to increase transparency across their vast service portfolios and associated supply chains. This is not only necessary because of sustainability but also to comply with legislative requirements (e.g., EU Taxonomy). However, corporate departments dealing with international assignments are not facing these challenges alone. They need to form partnerships (SDG 17) and collaborate with their vendors and internal stakeholders (enabling functions, corporate sustainability, procurements, etc.) to drive the much-needed change toward sustainable development.

About the Authors

Marina A. Schmitz serves as a Researcher and Lecturer at the Coca-Cola Chair of Sustainable Development at IEDC-Bled School of Management in Bled, Slovenia as well as CSR Expert/Senior Consultant at Polymundo AG in Heilbronn, Germany. She has worked as a Lecturer, Research Associate, and Project Manager at the Center for Advanced Sustainable Management (CASM) at the CBS International Business School in Cologne and the Chair of HRM and Asian Business at University of Goettingen.

Enno Ommen is working in Bayer AG’s Sustainability Excellence Office at CropScience Division. He had previously worked in the area of Global Mobility for about 10 years, which equipped him with profound knowledge in the field of expatriate management. He studied International Business (BA) at CBS International Business School and International Human Resource Management (MSc) at Manchester Business School. Further, as one of Bayer AG’s Sustainability Champions, Enno is supporting the sustainable transformation of the company.

Anja Karlshaus studied at the University of Cologne, Santa Clara University (USA), and the European Business School. In 2009, she took over the HRM professorship at CBS International Business School, later assumed the role of dean of the Business Administration faculty, before being appointed president. Moreover, she was previously employed at Dresdner Bank, Allianz and Commerzbank – being now member of various committees (Chamber of Industry and Commerce, City of Cologne, State of NRW). She researches sustainability, diversity, and agile HR.

Appendix

Full list of references:

Alamgir, F., & Alakavuklar, O. N. 2020. Compliance Codes and Women Workers’ (Mis)representation and (Non)recognition in the Apparel Industry of Bangladesh. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(2): 295–310.

Bader, B., & Berg, N. 2013. An empirical investigation of terrorism-induced stress on expatriate attitudes and performance. Journal of International Management, 19(2): 163–175.

Bader, B., Stoermer, S., Bader, A. K., & Schuster, T. 2018. Institutional discrimination of women and workplace harassment of female expatriates: Evidence from 25 host countries. Journal of Global Mobility, 6(1): 40–58.

Bader, A. K., Reade, C., & Froese, F. J. 2019. Terrorism and expatriate withdrawal cognitions: the differential role of perceived work and non-work constraints. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(11): 1769–1793.

Bailey, L. 2021. International school teachers: precarity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Global Mobility, 9(1): 31–43.

Bhanugopan, R., & Fish, A. 2008. The impact of business crime on expatriate quality of work-life in Papua New Guinea. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 46(1): 68–84.

Bücker, J., Poutsma, E., Schouteten, R., & Nies, C. 2020. The development of HR support for alternative international assignments. From liminal position to institutional support for short-term assignments, international business travel and virtual assignments. Journal of Global Mobility, 8(2): 249–270.

Bullough, A., & Renko, M. 2017. A different frame of reference: Entrepreneurship and gender differences in the perception of danger. Academy of Management Discoveries, 3(1): 21–41.

Chang, C., & Cooke, F. L. 2018. Layers of union organising and representation: the case study of a strike in a Japanese‐funded auto plant in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 56(4): 492–517.

Dickmann, M., & Bader, B. 2020. Now, Next and Beyond. Global Mobility’s response to COVID-19. RES Forum Research, 1.

Dickmann, M., & Watson, A. H. 2017. “I might be shot at!” exploring the drivers to work in hostile environments using an intelligent careers perspective. Journal of Global Mobility, 5(4): 348–373.

Faeth, P. C., & Kittler, M. G. 2017. How do you fear? Examining expatriates’ perception of danger and its consequences. Journal of Global Mobility, 5(4): 391–417.

Faeth, P. C., & Kittler, M. G. 2020. Expatriate management in hostile environments from a multi-stakeholder perspective – a systematic review. Journal of Global Mobility, 8(1): 1–24.

Fee, A., McGrath-Champ, S., & Berti, M. 2019. Protecting expatriates in hostile environments: institutional forces influencing the safety and security practices of internationally active organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(11): 1709–1736.

Fischlmayr, I. C., & Puchmüller, K. M. 2016. Married, mom and manager–how can this be combined with an international career? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(7): 744–765.

Gannon, J., & Paraskevas, A. 2019. In the line of fire: Managing expatriates in hostile environments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(11): 1737–1768.

Giorgi, G., Montani, F., Fiz-Perez, J., Arcangeli, G., & Mucci, N. 2016. Expatriates’ multiple fears, from terrorism to working conditions: development of a model. Frontiers in Psychology, 7: 1571.

Greppin, C., Carlsson, B., Wolfberg, A., & Ufere, N. 2017. How expatriates work in dangerous environments of pervasive corruption. Journal of Global Mobility, 5(4): 443–460.

Kirk, S. 2019. Identity, glass borders and globally mobile female talent. Journal of Global Mobility, 7(3): 285–299.

Lirio, P. 2014. Taming travel for work-life balance in global careers. Journal of Global Mobility, 2(2): 160–182.

McNulty, Y., & Hutchings, K. 2016. Looking for global talent in all the right places: a critical literature review of non-traditional expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(7): 699–728.

McPhail, R., & McNulty, Y. 2015. 'Oh, the places you won’t go as an LGBT expat!'A study of HRM’s duty of care to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender expatriates in dangerous locations. European Journal of International Management, 9(6): 737–765.

McPhail, R., McNulty, Y., & Hutchings, K. 2016. Lesbian and gay expatriation: Opportunities, barriers and challenges for global mobility. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(3): 382–406.

Ng, E. S., & Sears, G. J. 2017. The glass ceiling in context: the influence of CEO gender, recruitment practices and firm internationalisation on the representation of women in management. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1): 133–151.

Pinto, L. H. F., Bader, B., & Schuster, T. 2017. Dangerous settings and risky international assignments. Journal of Global Mobility, 5(4): 342–347.

Posthuma, R. A., Ramsey, J. R., Flores, G. L., Maertz, C., & Ahmed, R. O. 2019. A risk management model for research on expatriates in hostile work environments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(11): 1822–1838.

Stoermer, S., Davies, S. E., Bahrisch, O., & Portniagin, F. 2017. For sensation’s sake: differences in female and male expatriates’ relocation willingness to dangerous countries based on sensation seeking. Journal of Global Mobility, 5(4): 374–390.

Toh, S. M., & Denisi, A. S. 2005. A local perspective to expatriate success. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1): 132–146.

van Bakel, M. 2019. It takes two to tango: a review of the empirical research on expatriate-local interactions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(21): 2993–3025.

Walsh, P. R., Dodds, R., Priskin, J., Day, J., & Belozerova, O. 2021. The Corporate Responsibility Paradox: A Multi-National Investigation of Business Traveller Attitudes and Their Sustainable Travel Behaviour. Sustainability, 13(8): 4343.

Wilkinson, A., Knoll, M., Mowbray, P. K., & Dundon, T. 2021. New Trajectories in Worker Voice: Integrating and Applying Contemporary Challenges in the Organization of Work. British Journal of Management, 32(3): 693–707.

Wu, T.-Y., Liu, Y.-F., Hua, C.-Y., Lo, H.-C., & Yeh, Y.-J. 2020. Too unsafe to voice? Authoritarian leadership and employee voice in Chinese organizations. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 58(4): 527–554.