Introduction

When it comes to the increasing frequency and severity of natural disasters, are managers of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in denial about the risk and unprepared or are they ready to respond? As statistical evidence and popular press stories document the frequent occurrence of natural disasters and their devastation on businesses and the communities in which they operate, this is a critical and potentially existential question every company needs to consider.

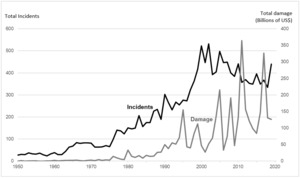

Natural disasters are a unique grand challenge that create a growing set of risks for MNEs at the local, regional, and global levels, as well as new challenges for research on MNEs. Figure 1 shows the number of incidents and total estimated amount of damage to property, crops, and livestock since 1960. The number and severity of disasters, while volatile, have been growing over the last several decades. This is due to several factors including increasing urbanization and climate change, among others (Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, & George, 2014; Kolk & Pinkse, 2008; Oh & Oetzel, 2022; Perrow, 2011; Rivera, Oh, Oetzel, & Clement, 2022).

Unlike other types of business risks – such as economic crises or political violence – natural hazards are often considered as unmanageable risks; risks that are seemingly impossible to avoid and over which individuals or organizations have little control (Oetzel & Oh, 2021; Oh & Oetzel, 2011; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Slovic, 2000). This widely held viewpoint compromises disaster preparation efforts and increases the risk that managers of MNEs and their subsidiaries will be left flat footed in the event of disaster. In practice, there is much that managers can do to prepare but it requires a change in mindset.

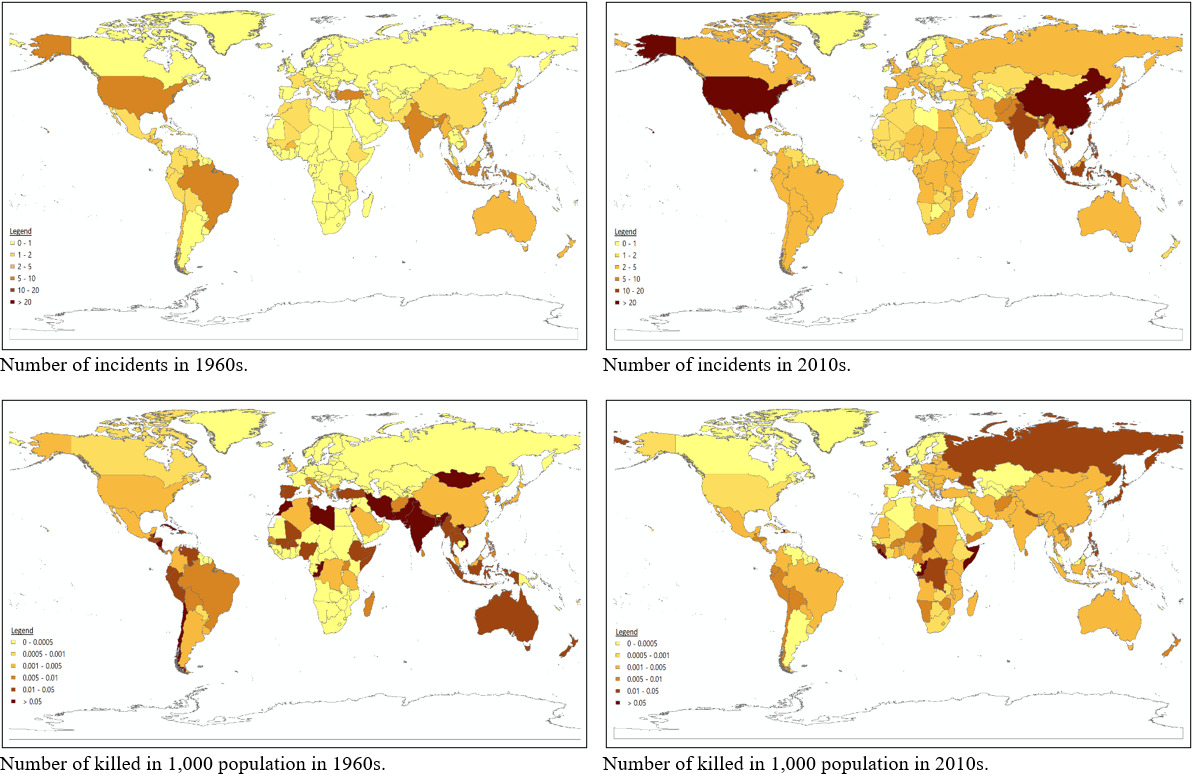

Figure 2 shows the incidents (a proxy of natural hazards) and number of people killed per 1,000 in the population (a proxy of natural disasters) by natural disasters across the world in the 1960s and 2010s. The number of people killed per 1,000 in the population has increased for several African and European countries, Japan, Philippines, and Russia, while it has decreased for North America, Latin America, and several Asian countries, including Australia. Considering the number of incidents has increased during this period in most countries, the differential patterns in these countries deserve attention. Notably, China, Indonesia, and the U.S. have very high numbers of incidents, but low numbers of people killed per 1,000 in the population in 2010s. In contrast, Russia has low number of incidents, but high number of people killed per 1,000 in the population.

One explanation for the variation in disaster deaths across countries is that certain locations may be prone to higher intensity events. Also, some countries are better prepared for disasters than others (Oetzel & Oh, 2021). For example, building codes are not always enforced (a function of corruption and/or poor code enforcement) so major structures may not be able to withstand certain types of natural hazards (Zilio & Ampuero, 2023). Reports suggest that this is one of the reasons that there were so many deaths after the earthquakes in Turkey in February 2023 (Bilginsoy & Fraser, 2023). While managers are unlikely to have an influence on the institutional issues that exacerbate risk, if they recognize the potential threats, they can mitigate them. Thus, regardless of the characteristics and the location of disasters, effective disaster planning and preparation by business and government can greatly reduce loss of life and property.

Research shows that as the likelihood of natural disasters increases, so too does the cost to the global economy (EM-DAT, 2022). The costs posed by natural disasters are extensive enough that they are recognized in federal tax policy for both individuals and businesses in U.S. Tax legislation. Legislation was originally enacted in response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, in New York City and they have now been extended to federally declared natural disasters in the U.S. Since 2001, any individuals or businesses affected by federally recognized natural disasters are eligible for tax relief. Such tax policies for the damages from natural disasters have also existed in other countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan, and South Korea, even before the outbreak of the 2019 novel coronavirus. Developing countries such as Ecuador and India are exploring the possibility of using taxes to finance disaster relief; something that MNEs should consider (Chatterjee, 2019).

Understanding Natural Disasters in the Context of International Business

Natural scientists categorize disasters into main types and subgroups. First, geophysical disasters originate from the earth and commonly include earthquakes and volcanic activities. Second, meteorological disasters include extreme temperatures, fog, and storms. Third, hydrological disasters include floods and landslides. Fourth, climatological disasters include droughts or wildfires. Fifth, biological disasters are exemplified by epidemics and insect infestations (EM-DAT, 2022).

Another way to characterize disasters is in terms of their onset (slow versus rapid), duration, scope (local, regional, or international), and impact. First, disasters may differ based on their speed of onset. Some disasters may occur suddenly while others are characterized by a slow onset. The 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China and the 2011 Japanese Tsunami did not provide institutions and organizations time to reduce the initial impacts given their lack of preparedness. Thus, the rapid onset disasters limit rationality in decision making, even for resource wealthy institutions or organizations. In the case of rapid onset disasters, it is too late to prepare once the disaster arrives. For slow onset disasters, however, there is a tendency to disregard disaster risk even though there may still be time to prepare.

In addition to the speed of onset, disasters vary in terms of their duration. Short disasters may share similar characteristics with rapid onset disasters and violent political events like terrorism attacks. For these events, it might be possible to prepare to a certain extent, but more difficult to predict and respond to the sudden occurrence of catastrophic events. As a possible solution for short-duration events that are difficult to manage, Perrow (2011) recommends that dispersing industrial activities is a solution for lowering vulnerability as a part of disaster preparation. However, when the geographic scope of natural disasters is very large, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, dispersing industrial activities might not be a good solution since the disaster is omnipresent. Instead, establishing duplicated and redundant supply chains across safe locations could be an alternative solution.

Thus, another factor that differentiates disasters is their scope. Disasters in one country have the potential to create both local and international problems. At the site of the disaster, MNEs risk damage to infrastructure, discontinuity to business, and threaten employees’ health and well-being. More broadly, their supply chains may be threatened in areas far from the disaster site. While governments at different levels can regulate the movement of human resources, financial capital, and goods and services across their borders, some types of natural disasters are multinational in terms of their scope and impact. Thus, natural disasters with a large scope may defy the sovereignty of borders complicating the management of, response to, and impact of, the disasters. These issues will be magnified when government policies and cultural norms differ across countries. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, there was confusion in how governments communicated about the risk. Also, the type and stringency of travel restrictions and other regulations varied widely across countries. Therefore, dispersion of supply chain could not be an optimal solution to deal with different government policies and cultural norms across countries.

Yet another important factor is the level of impact these disasters have across countries. If the potential impact is low, organizations may not prioritize issues around natural disasters. Impacts vary widely and are generally location-specific in nature. Thus, MNEs need to prepare for specific types of natural disasters in a host country. An added challenge is that MNE experience in one country may not be applicable to other countries limiting the ability of MNEs to leverage experiential learning in multiple markets. Some MNEs may try to “hedge” the risk through disaster insurance, but insurance is expensive and often not available in developing countries and emerging markets. Depending upon how a disaster is defined (e.g., is damage from a hurricane due to floods or wind damage?), insurance policies often fail to cover all losses; particularly disruptions to business. Other factors can also ameliorate or exacerbate the impact of a disaster. For instance, high quality local and national preparedness can mitigate, to a certain extent, the negative impact of disasters. Together, the characteristics of natural disasters described here will add to the challenges of MNEs.

Resilience Capabilities for MNEs

Natural disaster risk is challenging under any circumstances, but managers of MNEs have the added burden of learning about natural disaster risk across a variety of geographies. Fortunately, they need not develop all this information in-house. There are vast resources that exist in many countries. For example, information can be obtained from insurance companies such as the French insurance company’s AXA Climate Group, Chambers of Commerce, from the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) (when operating in the U.S.), from multi-lateral organizations such as the United Nations (UN) Environmental Programme and UN Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, among many others.

Nevertheless, the unique characteristics of natural disasters may challenge MNEs’ disaster preparation and response. Disaster preparedness requires MNEs to invest in establishing reliable relationships and formulating strategies and tactics that they may never have to use. If a disaster does not occur, preparation by MNEs may be seen as an “unnecessary cost” and a “wasted” expense by managers. For these reasons, the decision to prepare is an easy one for MNEs managers to delay or dismiss. While we have observed progress in disaster preparedness, there are still significant challenges to sustainable development due to the low levels of disaster preparation among businesses and institutions worldwide, coupled with the lack of knowledge about how to prepare (e.g., Hallegatte, Vogt-Schilb, Bangalore, & Rozenberg, 2017). As a result, managers of MNEs need to gain a better understanding of why and how they should develop firm capabilities around disaster management and what those capabilities should involve. Like other MNEs’ strategic choices, disaster planning and response requires a combination of location and non-location bound capabilities (Oh & Oetzel, 2022). Non-location bound capabilities include the ability to plan and respond to natural disasters, and ideally develop some capabilities that are transferrable across locations such as business continuity and recovery plans, resource inventory, communication and warning systems, employee training and organizational learning. For instance, the big picture issues around disaster preparation, response and recovery can be done at the corporate level of the MNE. Since there are aspects of disaster management that are common across types and locations, those can be disseminated across subsidiaries and subsidiary-level managers can adapt that knowledge to the local context.

In large complex organizations like MNEs, there is a need for high level strategizing around disaster risk. MNEs can leverage corporate resources, set corporate policy, and disseminate this knowledge across subsidiaries. Ultimately, however, effective disaster management relies on strong location-bound capabilities. Thus, given the characteristics of natural disasters that we discussed, these risks cannot be addressed solely with existing strategies and tactics. Rather, evidence suggests that firms need a different set of capabilities to manage them; specifically enhanced resilience. Resilience is an organizational capacity to absorb the impact of a shock and recovery from the occurrence of an extreme event. It includes location-bound capabilities like adaptability, flexibility, redundancy, agility, responsiveness, collaboration, and visibility (Ali, Mahfouz, & Arisha, 2017; Conz & Magnani, 2020; Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009).

Based on two key characteristics (scope and duration) of natural disasters that we discussed in the previous section, we categorized several types of natural disasters into each quadrant. We also recommended resilience capabilities based on the characteristics of natural disasters. Given the limited resources firms have, firms may like to provide priorities to develop these capabilities depending on disaster characteristics to which they are exposed.

The first characteristic is the geographic scope of natural disasters. For small-scale disasters, MNEs can develop adaptability by adjusting their response and internal processes. They should have a better understanding of changing external conditions through situation awareness such as early warning strategies and continuity planning to improve adaptability. However, for large-scale disasters, in addition to adaptability, MNEs need collaboration to prepare and respond to supply chain disruptions. Collaboration involves joint planning and information sharing with partners to coordinate the response. Information sharing and knowledge management are essential for building reliable and resilient networks. Visibility serves as a warning strategy, that provides firms valuable time to align their capabilities and minimize disruptive impacts.

According to a survey of 200 senior-level supply chain executives conducted by EY (Harapko, 2023), in the aftermath of severe disruption from the Covid-19 pandemic, firms had to improve their adaptability to new requirements for physical spacing, contact-tracing, personal protective equipment and remote work. These requirements varied across locations. Firms also needed to re-establish their supply chains after the crisis phase of Covid-19 pandemic, collaborate with other organizations, comply with government policies, and adapt to new technologies such as machine learning technology, and robotics, which generally meant hiring working with a new set of skills, and training employees how to manage the opportunities and threats of AI. The availability of such skilled workers and training also varies across locations. These examples illustrate the type of adaptability, collaboration, and visibility needed by MNEs.

The second characteristic is duration. For short-duration disasters, MNEs need agility, which involves a prompt response while maintaining existing structures and strategies. Agile firms have increased velocity, acceleration, responsiveness, and the ability to recombine resources. To improve agility, firms can cultivate knowledge management through education, training, and simulations in the pre-disruption phase that constitutes risk management culture. For long-duration disasters, firms need more than agility. They may develop flexibility and redundancy. Flexibility involves implementing rapid decision-making processes, quick communication, and fast learning to adapt to changing conditions. Redundancy means keeping some resources in reserve to be used in case of necessity. To be able to establish flexibility and redundancy within MNEs, firms should be resourceful and (re)configure challenges and opportunities faced by each actor in their networks to maintain the flexibility of the structure and strategy of their networks.

The volcano that erupted in Iceland in 2010 and eventually generated an ash cloud across large parts of Western Europe is an example of a long duration disaster. Eyjafjallajökull began erupting on March 20 leading to a period of activity that lasted until April 12. The ash cloud that then began on April 13th grew and expanded over large parts of western Europe. On April 15th, planes began to cancel flights. By late April, experts believed the crisis was over. Yet on May 3rd, the ash cloud returned and did not subside until late May. The volcanic eruption caused significant flight disruptions across southern Europe. While many other airliners cancelled their flights in Europe, Korean Air took advantage of the extended duration of the disaster to prepare. They developed a contingency plan specifically for this situation. On April 15th, when its flight to London had to redirected to Paris and then Frankfurt, Korean Air demonstrated their preparedness by arranging hotel accommodations and leasing busses to transport passengers across the Straits of Dover into the U.K. (Lee, 2010; Oh & Oetzel, 2022). This provides examples of agility, flexibility, and redundancy.

Of course, the contextual specificity of natural disasters may limit the benefits of knowledge and experiential learning from conventional mechanisms such as international intra- and inter-organizational knowledge transfers and learning, which may make it difficult to recombine non-location bound and location-bound capabilities. For these reasons, the development of effective multi-sector partnerships is critical (Oh & Oetzel, 2022). When effective, these collaborations can significantly lower risks associated with disasters, reduce the costs of disaster management to any one organization, and improve organizational resilience for those involved. Utilizing multi-sector partnership will be very important when MNEs’ internal network configuration and information sharing have challenges due to long duration and large geographic scope of natural disasters. However, given the different interests of actors, multi-sector partnership will be more effective when the roles and responsibilities of participating actors are clear. If not, then the overall effectiveness of the partnership may be threatened (Alerts & Mysiak, 2016).

Identifying the right actors in government, particularly at the local and regional level, is also key to formulating effective preparedness strategies. For instance, innovative insurers such as the AXA Climate Group, can provide valuable information and customized products for specific disasters and locational risks. Chambers of Commerce can also offer helpful resources and identify potential partners for preparing for and responding to disasters.

In sum, expertise on disaster risk management need not be developed solely in-house. In fact, relying on external experts for uncertain events may be the most cost-effective strategy for reducing risk since disasters occur irregularly with uncertain severity. Thus, managers can learn from disaster experts who can provide the latest information on strategies and tactics for preparing for and responding to disasters. Seeking out experts in disaster management has not traditionally been a top priority for managers. Yet given the increasing risk of disasters and the heavy financial toll they pose, doing so is a critical part of managing business risk.

Conclusion

A series of international business and management studies paid attention to the impact of health crises and catastrophic events on organizations and individuals after the burst of Covid-19 pandemic and the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Yet, the scope and severity of natural disaster risk, and the potential for cascading disasters, are only expected to grow over the coming decades. Climate change, geopolitical conflict, and the political inability of countries to collectively address the threat of climate change, will only lead to an increasing number of natural disasters and other exogenous shocks worldwide. It is also important to note that natural disasters should be considered in a corporation’s risk management portfolio. Doing so will not only make strategies more effective but also enable managers to consider the holistic set of risks a company may face.

In the absence of government intervention and international cooperation, and the limits on the ability of insurers to underwrite natural disaster risk as the costs increase, MNEs must take responsibility for mitigating risk to their employees, operations, and global supply chains. The starting point for managers should be an accurate understanding of the risks of natural disasters, the ability or inability of government to address the challenges, and the identification of potential cross-sector partners that can help managers address major threats to business. An important first step is to understand organizational exposure to the natural disaster risks and the characteristics of natural disasters to identify capabilities they need to develop to improve organizational resilience.

With the abundance of information now available about the risk of natural disasters, any companies that are not prepared for these risks may face allegations of negligence if managers have not taken steps to mitigate the threats. No one can fully prevent natural disasters from happening, nor control where and how long they occur. However, there is a substantial amount of location-specific information available about this growing threat. By customizing various programs, tools, techniques, and strategies, managers can enhance the resilience of their businesses to natural disasters. Will your business be prepared to respond when the time comes?

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. Shuna Ho for her assistance on GIS mapping.

About the Authors

Dr. Chang Hoon Oh is the William & Judy Docking Professor of Strategy in the School of Business, University of Kansas. His research interest includes non-market strategy, business continuity and sustainability, and geographic scope of multinationals. Since 2006, he has extensively studied firm strategies for managing and preparing various non-market risks such as natural disasters, climate change, technological disasters, political conflicts, and social conflicts. He has collaborated with various organizations such as WWF-U.K., CIRDI, UNDP, and EY-Korea.

Dr. Jennifer Oetzel is Professor of Strategy and Kogod IB Professor at American University. Her research focuses on business adaptation to climate change and disaster risk management. She has won multiple research awards and co-authored a book published by Cambridge University Press in 2022 entitled, Business Adaptation to Climate Change. Her work has appeared in the Strategic Management Journal, Organization Science, Harvard Business Review, and the Journal of International Business Studies, among numerous other outlets.