Introduction

Being a good researcher is not about achieving short-term perfection. Academic careers require a lifetime of investment in academic capability building. Researchers thus continue to seek opportunities to acquire new skills and knowledge through for instance workshops, conferences, and sabbaticals. However, there is little explicit guidance on how to choose between these activities and how to make the most of them. How can we plan and manage our own learning more effectively? What should be considered when acquiring new skills/knowledge for academic knowledge creation?

In this article, we suggest applying IB concepts and knowledge to our own profession. As an international business (IB) field, we study the mobility of people (expatriates, inpatriates, and migrants), but many academics are mobile too, both permanently and temporarily. As an IB field, we study knowledge creation and knowledge transfer, but as academics we are prototypical knowledge workers who create and transfer knowledge. Using Nonaka’s knowledge creation theory and a recently published JIBS framework on mobility and subsidiary capability building (Kim, Reiche, & Harzing, 2022) as a lens, this short piece illustrates what we can learn about our own profession by applying IB concepts and knowledge. We use the lived experience of the first author as an illustrative case study.

Why Nonaka’s Theory is so Relevant to Academia

Nonaka’s theory focuses on the dynamic human processes needed to create knowledge in organizations. The key concept of organizational knowledge creation theory (OKCT) is knowledge conversion which is based on how two types of knowledge (tacit and explicit) interact to create new knowledge. At an individual level, “knowledge creation can be understood as a continuous process through which one overcomes the individual boundaries and constraints imposed by information and past learning by acquiring a new context, a new view of the world and new knowledge” (Nonaka, von Krogh, & Voelpel, 2006: 1182).

For academics, creating new knowledge is our raison d’être. As knowledge in academia is largely tacit and embedded in individual researchers, it can only be truly shared and diffused by intensive day-to-day interactions among researchers, which underscores why OKCT is highly relevant in explaining knowledge acquisition, transfer, and new knowledge creation in an academic context. Drawing on Nonaka’s definition of organizational knowledge creation (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995), academic knowledge creation can be defined as the capability of an individual researcher to create new knowledge and disseminate it throughout academia and society. The tacit knowledge embedded in individual researchers lies at the heart of the academic knowledge creating process, and it is mobilized through dynamic interactions among researchers. Given that tacit knowledge can only be transferred through personal interactions, an effective design of an individual researcher’s knowledge acquisition activities is crucial to improve their knowledge creating capability.

A Framework: Academic Capability Building and Knowledge Creation

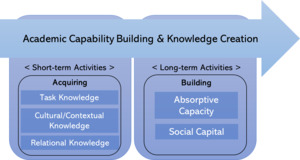

When it comes to knowledge acquisition, there are usually two parties involved: a knowledge holder and a knowledge seeker. Typically, the knowledge seeker travels to the knowledge holder’s place / institution to acquire their knowledge. When reading a recent JIBS article (Kim, Reiche, & Harzing, 2022) on knowledge acquisition and knowledge transfer for business inpatriates, we were struck by how each of the components of its theoretical model appeared to be mirrored perfectly in the first author’s recent academic mobility experience. Figure 1 shows a framework for academic knowledge creation which we adapted and modified from Kim et al. (2022).

When a knowledge seeker attempts to further develop their academic capability, they need to plan short-term and long-term activities. In the short-term, the knowledge seeker should consider how to acquire task, cultural/contextual, and relational knowledge from knowledge holders. These short-term activities lay the ground for building absorptive capacity and social capital in the long-term, but additional efforts are necessary to realize their potential. We will elaborate on this using the first author’s lived experience as an illustrative case.

Short-Term Activities for Academic Knowledge Creation

I, the first author of this article, am a Korean national who completed her master’s and Ph.D. degree in Japan and has been teaching in Japan for about 10 years. The first author visited the second author in London for a one-year sabbatical in 2019.

Acquisition of Task Knowledge

The main purpose of this sabbatical was to acquire research-related knowledge, i.e., task knowledge. In my case, this involved learning to develop a paper for publication in international journals and acquiring practical knowledge on qualitative research methods. To make most of my one year in London, I thus participated in many conferences, seminars, and workshops, and more specifically, paper development workshops where I could observe how other researchers developed their papers. This provided me with an excellent insight and understanding into what to do and how to do it. Until then, I had only read the ‘end products’ of their research, i.e., the papers published in international journals. Having the opportunity to discuss the ‘product development process’ provided me with a deep understanding about what constitutes a good paper by global standards. In terms of qualitative methods, I had only acquired a little knowledge, mainly from textbooks. Fortunately, I discovered that there were lots of courses and workshops held at various universities in the U.K. So, I attended as many as my time and budget permitted. Through these, I was able to acquire the knowledge shared generously among fellow qualitative researchers.

Acquisition of Cultural/Contextual Knowledge

Improving my knowledge of Western academic culture was also an important purpose of my sabbatical. I learned something very important that straddles language and culture: how to communicate with clarity with non-Japanese researchers. In Japan (and Korea too), there is a lot of tacit communication, as well as the use of ambiguous expressions that are well understood among insiders. In many Asian cultures, messages are often conveyed implicitly, requiring the listener to read between the lines, which is sometimes expressed as ‘listening to the air’ (Meyer, 2014). While participating in meetings abroad, I learned that I needed to apply a very clear and direct communication style to avoid misunderstandings and ambiguity. It was the same when collaborating on a paper. I did not realize that many of my sentences and expressions were unclear to readers until my co-authors (who are Western academics) picked them up. Thus, the diverse and repeated experience of communicating with researchers outside Japan enabled me to develop the sense of clarity of expression that is taken for granted in these academic circles.

Acquisition of Relational Knowledge

Relational knowledge is defined as knowledge of “who knows how to do what” (Duvivier, Peeters, & Harzing, 2019). Similarly, during my sabbatical I had the opportunity to meet many researchers and was able to build up strong relationships with some of them. First, meeting researchers at my host university and other universities in the U.K. gave me important insights into how they exchange information on research resources and how they help each other to develop their research. Second, the CYGNA (see https://harzing.com/cygna) network – a network to support female academics in Business & Management and the wider Social Sciences – provided a very friendly atmosphere, in which I could find both role models and psychological support. Lastly, I met and developed good relationships with some Korean researchers working in European Universities. They shared their experiences about studying and researching in Europe and gave me helpful advice on understanding European academia from a Korean perspective. Having many face-to-face meetings with various groups of academics enabled me to keep, and even extend, my network through online meetings and email exchanges after I came back to Japan.

Long-Term Activities for Academic Knowledge Creation

Absorptive Capacity Building

Absorptive capacity is defined as the “ability of a firm to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends” (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990: 128). In our context, it refers to the ability of academics to access and acquire the necessary knowledge from other academics, utilize it to do research and disseminate the outcome. The various types of knowledge acquired in the short-term become activated only when a knowledge seeker tries to create new knowledge by using them. In the process, a knowledge seeker combines their own tacit knowledge with that of knowledge holders to create new knowledge, through a process called knowledge conversion in the OKCT. Upon my return to Japan, I was lucky enough to co-author a paper with my host and another researcher, which was accepted at a top international journal. The co-authoring process required continuous, repeated, and close interactions, through which I learned by doing from two established researchers. As the knowledge acquired through short-term activities is highly volatile, a long-term plan for how to solidify and embody it into a concrete outcome is critical. If successful, this plan then upgrades a knowledge seeker’s absorptive capacity, through which a subsequent knowledge seeking, acquisition, and creation cycle may be accelerated.

Social Capital Building

Social capital is the structure and content of individuals’ networks (Adler & Kwon, 2002). The task, cultural/contextual and relational knowledge acquired in the short-term provide rich resources to further build and strengthen social capital in the long-term. I was very fortunate to be able to continue intensive conversations with my host after I came back to Japan, because we started co-authoring a paper. We exchanged e-mails almost every week to develop our paper until it was accepted, and continued our frequent conversation about a new project and another paper. A continued flow of information between myself in Japan and researchers in the U.K. was also facilitated by the CYGNA network meetings, which were conducted online after the COVID19 pandemic struck. The extended social capital helped me to upgrade not only my research, but also my teaching. In cooperation with another CYGNA member I designed and conducted a virtual team project with collaboration between Japanese and Irish students. Moreover, I’m now part of the CYGNA organizing team for the Asia Pacific region. Through these experiences, there was a dramatic change in my identity as a researcher. I was a domestic researcher until 2019, and a visitor to London during 2019. Now, I think of myself as a member of an international academic community, which is a huge change of perspective.

Application to a Domestic Workshop in Japan

Although sabbaticals in a foreign institution are very powerful opportunities for academic capability building, our framework of academic knowledge creation can also be applied to various domestic opportunities. A recent example is a management theory workshop held in Japan in the Summer of 2023. Prof. Shige Makino, who is a well-known knowledge holder, conducted an 8-day workshop for members of JAIBS (Japan Academy of International Business Studies). About 20 passionate knowledge seekers participated, gave presentations, and engaged in discussions under Prof. Makino’s guidance.

During the 8 days (short-term), we acquired knowledge on management theories (task knowledge). Prof. Makino provided us with insights into how these theories have developed and how we can apply them to real world events (cultural/contextual knowledge). The diverse research interests and experiences, not only of Prof. Makino, but also of the other participants gave me a deeper understanding of who does/knows what in my research community (relational knowledge). However, the considerable learning from this workshop would easily fade away unless I actually applied a certain theory to my own research projects and experienced the writing up and review process firsthand (absorptive capacity building). Moreover, it would take additional efforts to engage in further contact with and embark on a research collaboration with some of the other participants (social capital building).

In some cases, short-term activities to acquire task, cultural/contextual, and relational knowledge might lead to long-term activities (absorptive capacity and social capital building) and new knowledge creation, even without intentional action. However, by understanding this knowledge creation process more clearly, we can plan backwards. With a clearer aim of what knowledge we want to create, we can plan what kind of absorptive capacity and social capital is necessary to achieve this, and what type of knowledge acquisition we need to seek.

Recommendations to Improve Academic Capability Building

Just like companies, academics have only limited resources to spend on developing our capabilities. Thus, how and where to allocate our time and efforts should be carefully planned to realize our own growth. Figure 2 shows the temporal nature (short and long-term) and intensity (low and high) of sample interactions that are common in academia. We classified conferences, seminars, and unplanned sabbaticals as volatile experiences, whereas we see interactive workshops, the journal review process, co-authoring, and purposeful sabbaticals as academic capability building activities. The OKCT, absorptive capability, and social capital theory lenses provide us with explanations as to why these highly intensive interactions help us to further build our academic capability. Applying these theories more systematically to consider which knowledge to acquire to build new capability, how to enable intensive interactions, and how to maintain access to information could provide more in-depth insights than we were able to provide in this short piece.

We derive three actionable recommendations for (junior) academics from figure 2. First, if you have only limited time and need to choose between either a conference or a workshop, participating in an interactive workshop rather than a conference might be more beneficial to acquire the kind of task, cultural/contextual, and relational knowledge that lay the foundation for long-term knowledge creation.

Second, the co-authoring and journal review process enables very intensive interactions between authors, and between authors and editors/reviewers, which allows for the exchange of tacit knowledge between the relevant parties that results in new knowledge creation. When co-authoring, authors put forth their ideas and opinions in the process of developing a paper, verbalizing and combining each other’s tacit knowledge. Subsequently, in the journal review process, authors externalize their own tacit knowledge through writing up a manuscript, which constitutes explicit knowledge. Editors/reviewers then try to comprehend (internalize) the manuscript with their own tacit knowledge, suggesting ideas on how to create more rigorous and impactful knowledge. For this process to work as intended reviewers need to be constructive critics rather than gatekeepers, and authors need to be responsive and treat a revise and resubmit decision as an opportunity to further improve their paper rather than just “jumping the hurdles”.

Third, we suggest that a purposeful sabbatical provides an excellent opportunity for academics to further improve their knowledge-creating power. As shown in the case above, a long-term sabbatical helps us to expand our boundaries by intensively interacting with a large number of academics with different types of knowledge and interests, representing different social practices, and coming from diverse demographic groups. Academics’ diverse tacit knowledge is a source of creativity, thus, through knowledge conversion, we may discover new ways of defining problems and searching for solutions (Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009).

Although in this article our focus has been on what individuals can do to improve their capacity for knowledge creation, both professional associations such as the Academy of International Business and individual universities can also play a crucial role in this. For instance, the format of academic conferences could be redesigned to maximize the value of face-to-face meetings which encourage intense individual interactions and lay the foundation for the participants’ long-term academic capability building. This requires a clearer distinction between what can be done online (e.g., research presentations, research methods seminars) and what can only really be done face-to-face (e.g., trust/network building, professional/paper development workshops). The latter activities should thus be strengthened to make onsite conferences more meaningful. Moreover, universities could reconsider the tradition of allocating resources mainly for sponsoring paper presentations at conferences and seminars. Instead, they should consider investing resources into (mini)-sabbaticals and interactive workshops, encouraging their faculty members to prioritize activities for academic capability building over volatile experiences.

In sum, a better understanding of the academic capability building and knowledge creation process can help the various actors in academia to reexamine their conventional practices that largely originate from a time that any access to academic knowledge required face-to-face interaction. Easy online access of both published articles and preprints and virtual research communication meetings could free up face-to-face contact for what it is uniquely suited to: the process of trust building that is an essential prerequisite for tacit knowledge sharing, and the energy manifested through co-presence that is a key facilitator for action (Collins et al., 2022).

Conclusion

As a profession academics are one of the most mobile groups of employees; they are also prototypical knowledge workers. Yet we know very little about their experiences and the challenges they face in improving their capabilities for knowledge creation. As shown in this article, individual mobility and knowledge creation in academia can be productively analyzed through the lens of IB theories. However, this is by no means the only area where we can apply IB theories to our profession. FDI and entry mode theories could be used to analyze the creation of branch campuses. Theories about control mechanisms between HQ and subsidiaries could likewise be applied to university branch campuses in other countries. The influx of migrant academics in many countries would provide a good platform to study EDI, cross-cultural communication, and multi-cultural and multi-lingual teamwork. The possibilities are endless. Maybe it is time we start applying our academic theories to our own profession more systematically? Through this process we might be able to build the much-needed solid foundation for informed decision-making and leadership in current-day academia.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful for the guidance and constructive comments of Editor William Newburry and the two anonymous reviewers. We also thank Paul Gooderham and Sebastian Reiche for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of our manuscript. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP20243632.

About the Authors

Heejin Kim (PhD University of Tokyo) is an Associate Professor of International Business at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan. Her research interests include subsidiary capability building, knowledge transfer of MNCs and international HRM.

Anne-Wil Harzing (PhD University of Bradford) is a Professor of International Management at Middlesex University London and visiting professor at Tilburg University, the Netherlands. Her research interests include international HRM, HQ-subsidiary relationships, and the role of language in international business. In addition to her substantive research areas, Anne-Wil has a keen interest in issues relating to the evaluation of research performance metrics as well as diversity and inclusion in academia (https://harzing.com).