Introduction

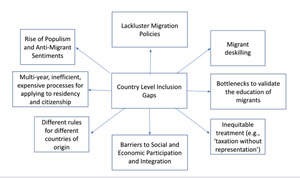

The number of international migrants worldwide has increased significantly over the last two decades, reaching up to 281 million - 3.6% of the global population (International Organization for Migration, 2022). Migrant entrepreneurs generate jobs, bring cultural diversity, and represent a significant contingent of low- and high-tech entrepreneurs in most developed nations, contributing to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) strategies (Newburry, Rašković, Colakoglu, Gonzalez-Perez, & Minbaeva, 2022). In addition, their trajectory “from informality to formality” is a valid aspect of strategizing. Nevertheless, some are “born as citizens and reborn as aliens” due to several harsh migration policies and barriers that prevent them from accessing equal opportunities as local mainstream citizens (Kothari, Elo, & Wiese, 2022). Therefore, the literature points out several inclusion gaps that these migrants face. Figure 1 depicts these gaps.

These inclusion gaps are reflected in the widely studied topics of liability of foreignness (LOF)[1] and outsidership[2] (LOO) (Lagerström & Lindholm, 2020; Zeng & Xu, 2020). Given the informal aspects of most migrant entrepreneurs, these liabilities might be even larger. Nevertheless, being a migrant entrepreneur may reduce the toll of being an ‘alien’. This is because entrepreneurship may act as a tool for social integration (Mago, 2023). We believe that the practical side of strategizing lacks exploration. Because of that, we intend to focus on how migrant entrepreneurs may apply their foreignness to their business marketing strategy to explore business opportunities.

In this context, migrant liminality is sometimes overcome by their intercultural experiences, which promote abilities that help to identify promising business ideas and the creation of innovative solutions, and bring innovative approaches, or exotic products and services that might be appealing in their new habitats (Newburry & Ohri, 2023; Vandor & Franke, 2016). In addition, cultural differences between entrepreneurs and host societies are both a source of opportunities and challenges, which can be explored to create new value in both established and new ventures (Zhou, 2004). These differences may exert xenophobia, and protectionist and populist discourses, which creates tensions within the social fabric. Nevertheless, the same cultural differences could generate curiosity and attraction, such as in gastronomy, clothing, or music. Thus, this article focuses on actionable recommendations for migrant entrepreneurs regarding their foreignness as marketing strategies to access business opportunities. We highlight the challenges and choices to be made by them in order to transform LOF and LOO challenges into market opportunities and short-term survival into successful business ventures, generating new types of businesses, or supplying new products and services to the host societies.

Challenges of Migrant Entrepreneurs

Migrant entrepreneurs struggle to participate and become integrated into the host society. They must deal with several challenges to their business ventures. Most of these arise due to both LOF and LOO (Kothari et al., 2022). Their complexity is even higher than migrants pursuing other activities since most migrant entrepreneurs start informal businesses.

Considering the LOF, cultural adaptation challenges involve the understanding of local norms, mastering the local language, and being able to communicate with customers and suppliers (Zaheer, 1995). For a migrant, finding a job as a nurse or an engineer, for instance, demands proficiency in the local language and complex diploma validation. As opposed to that, serving their ethnic communities, selling ethnic grocery goods, and having ethnic employees, does not require hardly any cultural adaptation, even while living in a foreign land.

In regard to the LOO, business networks are generally seen as a source of prospective customers, suppliers, and resources that are not obtained anywhere else, being a catalyst of the entrepreneurial process (Coviello & Munro, 1997). These networks may promote access to alternative financial resources and traditional knowledge, abilities, and ethnic culture rather than formal knowledge, which is obtained through education (Zhou, 2004). Moreover, although they might belong to a certain ethnic group, creating new social networks might be challenging (Elo, Ermolaeva, Ivanova-Gongne, & Klishevich, 2022), but crucial to their business success. Thus, migrant entrepreneurs and their social networks are based on connections with both customers and inter-firm alliances that influence the co-creation of opportunities.

LOF and LOO have been vastly studied by International Business scholars. Based on that, we show how migrant entrepreneurs might use their foreignness to their advantage to adapt their marketing strategies and do well marketing-wise.

Overcoming Challenges through Marketing Strategies

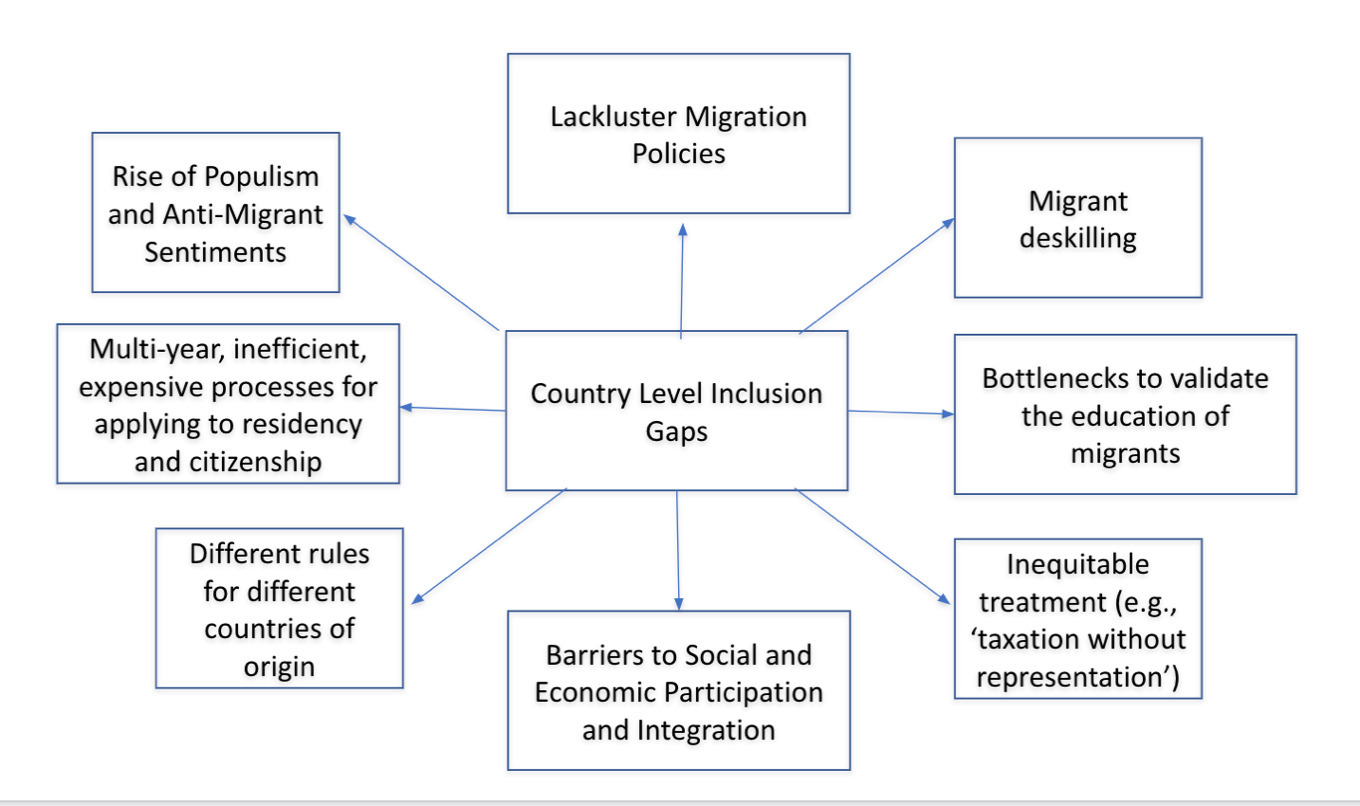

Most migrants become entrepreneurs as a form of economic adaptation and subsistence. In this vein, we showed how migrant entrepreneurs face a series of challenges related to both LOF and LOO. Nevertheless, the migrant aspect of these entrepreneurs might also give them an edge. Figure 2 shows the main challenges arising from these liabilities and opportunities for being a migrant entrepreneur.

A starting point to access these opportunities is to formulate their market strategy. In this vein, Ansoff’s matrix (Grünig, Kühn, & Morschett, 2022) provides the entrepreneur with a set of choices on how to position their business. Based on this market-product matrix, we argue that migrant entrepreneurs’ positioning decisions are based on being affiliated to their own community or not, while targeting their ethnic market or not. Thus, they base their business strategies in the cultural specificities of their communities—within and across national boundaries (Kothari et al., 2022), which can influence several aspects of their businesses, such as (i) market orientation (e.g., targeting migrant consumers or locals); (ii) growth expectations (e.g., whether to remain small or expand internationally); and (iii) survival strategies (e.g., whether to continue to cater to migrant consumers within the ethnic enclave or to expand to ethnic-friendly local consumers). We show these business strategies in Table 1.

Considering these market opportunities, we argue that migrant entrepreneurs who are socially identified (or affiliated) to their ethnic communities might use their community networks as a source for raw materials, employees, and ethnic consumers. These are typically found in ethnics enclaves, such as Chinatowns – a concentrated urban space explored by one ethnic group (Zhou, 2004). Hence, entrepreneurs focusing on ethnic consumers will choose businesses that are tied to their communities by tradition, prestige, or even lack of opportunity (or barriers) to explore business opportunities focusing on local customers. They can focus on ethnic customers, such as Chinatown entrepreneurs who cater to their own ethnic group (grocery stores, restaurants, Chinese medicine herbalists), small Brazilian bakeries and Cuban restaurants in Florida; or they might choose to focus on ‘exotic’ products/services, such as Brazilian steakhouses and Brazilian jiu-jitsu, catering to local mainstream customers that appreciate those products and services.

On the one hand, entrepreneurs focusing on ethnic niche customers depend fundamentally on the size of the community. A small group may not generate enough consumption, but larger communities present greater internal competition and attract firms to the ethnic market. Their main challenges identified are (i) locating the ethnic community to support the business. Migrant communities are part of various social networks in different countries around the world. Knowing the type of ethnic customer who lives in the given country or region helps the entrepreneur start mapping their business; (ii) locating local sources of inputs and raw materials to provide services/products. Entrepreneurs who want to migrate to a certain country and venture straight away suffer more from this issue. Spending time working, even if underemployed, is fundamental. Cleaning houses, serving as a waiter or babysitter should not just be a temporary means of support, but rather a ‘market education’ process – or a ‘migrant hands-on MBA’; and (iii) getting to know the local regulations. Informality is a path that many migrants use to start their businesses. Selling goods door to door, providing services at home, etc. cannot be business strategies, as they generate complaints and distrust between business owners and customers. A strong ethnic community has lawyers and accountants who should be sought out to formalize business.

On the other hand, when focusing on providing ‘exotic’ products/services to local customers, their challenges are to adapt their products and services to the local taste, demanding prototyping of recipes, market and consumer research, marketing efforts, sampling, and ‘evangelism’ to the ethnic culture. The market for exotic products/services for local customers presents, as a first challenge, knowledge of local legislation. For example, migrants from relational cultures may accept buying a product without a receipt, but those from more contract-based cultures may not like this. Another challenge is adapting the product or service. It will not always be possible to indoctrinate the local consumer to the migrant way of doing things; this requires time and effort. In this case, it is better to pursue actions such as adapting ingredients, e.g., sugar/salt content, and changing the product nomenclature (e.g., from stew to ‘Brazilian goulash’).

In relation to migrant entrepreneurs that are not affiliated to their ethnic communities, we observe that their market strategies focus on either providing non-niche specific products/services for the ethnic community or engaging in highly competitive markets. Examples are those insurance and banking firms that target specific ethnicities, such as health and car insurance firms in Toronto, which focus on Brazilian customers. The challenges these migrant entrepreneurs face may include lack of in-depth knowledge of the legislation and regulations of local products and services, understanding how to ‘translate’ them into migrant culture, and identifying what features, characteristics and configurations would be most valued by their target audience. Their particularity is that sometimes they manage to minimize their labor costs through hiring close relatives or family members that accept working long shifts for low wages. Thus, these business configurations of dependence on family members’ work allow them to secure a positions of economic preeminance, which might bring fierce competition from native entrepreneurs.

In order to soften the mentioned threats, entrepreneurs providing non-niche specific products/services for the ethnic community might want to establish clear competitive differentials and premium services. They could hire local native speakers, or conduct best practices training with their teams. In terms of products, packaging and service could represent added value to undifferentiated products. By doing so, migrant entrepreneurs can guarantee the supply of high quality items.

Also, for migrant entrepreneurs aiming to complete in highly competitive markets, their businesses must focus on the general public of the host country – the mainstream local customers. In this case, the Turkish in Germany and Denmark, and the Pakistanis in England owning 24-hour grocery stores are examples of these types of migrant entrepreneurs. Their challenges encompass fluent communication in the local language, access to credit/loans to face competition, creation of competitive differentials, such as working extra hours (or 24x7), and having a premium location (in the case of grocery stores). In addition, these entrepreneurs might struggle to gain knowledge on local regulations.

These migrant entrepreneurs serving local mainstream customers can manage their challenges with similar strategies as those focusing on ethnic customers; however, conformity to local habits, rules and language are keys to success. While targeting local mainstream customers, they would be exploring a much larger potential market. But, to seize opportunities, they should be prone to fierce competition and quick adaptation of changing mainstream customer habits. The specificities of those serving ethnic communities and those serving highly competitive markets also provide a set of different strategies to overcome their challenges. Concerning the first, tradition, and conformity to migrant culture is key. The latter demands the opposite, conformity to local mainstream culture and rules. Thus, it is expected that both types of entrepreneurs understand these contextual factors. By following a few of these suggestions, migrant entrepreneurs may reduce their venture risk.

Conclusions

Migrants suffer a series of inclusion gaps when arriving in new locations. Several of these gaps are explored in the International Business literature as both LOF and LOO. Nevertheless, migrant entrepreneur informality and lack of knowledge might boost both liabilities. In this regard, we showed how migrant entrepreneurs may use their foreignness to turn both LOF and LOO into business opportunities. They can do so by adapting their marketing strategies accordingly based on their affiliation (or not) to their ethnic communities and the targeted audience. We discussed the market challenges that migrant entrepreneurs may face to provide their products and services to different audiences (e.g., locals or coethnics). We also show how they can overcome these challenges by adopting different market strategies.

The paper also brings practical insights and reflections for future ethnic/migrant entrepreneurs that are embedded in a foreign society, facing cultural differences, highlighting the challenges and market opportunities, strategies and choices to be made by them in order to succeed in their businesses.

We acknowledge that the overall institutional environment of a country or locality, including migration and integration policies for migrants, might also influence the performance of the four types of entrepreneurial market strategies depicted in this paper. However, this is not considered in our approach and might be subject for future investigation. In addition, the institutional environment and public policies can target education and training to develop skills of migrant entrepreneurs, and promote an inclusive environment, influencing the economic growth of the host nation.

About the Authors

Roberto Pessoa de Queiroz Falcão is a professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at Universidade do Grande Rio, Brazil and part of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Brazil team. He holds a Ph.D in Management from PUC-RJ. His research interests are in the intersection between strategy and immigrant entrepreneurship. He is also the co-leader of the Immigrant and Refugee Entrepreneurship Research Project (UFF/UNIGRANRIO). Outside of the academia, the is a CNPq SEBRAE Fellow - ALI Project.

Bernardo Silva-Rêgo is an assistant professor at UNIGRANRIO, Brazil. His research focuses on internationalization process and policies, nonmarket strategies, and the influence of blockchain emergence in firm strategies. He has been published in journals such as Journal of International Business Policy, International Marketing Review and Journal of International Management. Outside of academia, he has been providing strategic consultancy for entrepreneurs and startups.

Eduardo Picanço Cruz is the Coordinator of the Executive MBA in Entrepreneurial Management and an Associate Professor IV of the Department of Entrepreneurship and Management at the Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), Brazil. He holds a Ph.D.. in Chemical Engineering from the UFRJ. His research interests are in the intersection between strategy and immigrant entrepreneurship. He is also the leader of the Immigrant and Refugee Entrepreneurship Research Project (UFF/UNIGRANRIO).

The concept of LOF assumes that foreign firms have disadvantages when facing domestic firms, such as institutional and communication knowledge (Zaheer, 1995).

The concept of LOO assumes that foreign firms have little or no access to relationship networks in the host country, which impedes access to business opportunities (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009).