Introduction

The internationalization of emerging market MNEs (EMNEs) has been a popular topic in the past two decades as IB scholars have been trying to understand the distinctive features of the entry model, speed, role of state, role of institutions, and other key aspects of the internationalization of EMNEs compared with their Western peers (Luo & Tung, 2018). New theories, such as springboard theory (Luo & Tung, 2007, 2018) and composition-based view (Luo & Child, 2015), have emerged to answer the call for an understanding of the unique features of EMNE internationalization.

The springboard perspective proposed by Luo and Tung (2007) argues that EMNEs are using international expansion as a springboard to acquire strategic resources and assets, and/or reduce the institutional and market constraints in the home country. The springboard perspective has provided a profoundly insightful framework for understanding the motives and behaviours of EMNEs in their initial stage of internationalization as it mainly focuses on the entry stage of international expansion through a foreign direct investment (FDI) lens.

However, the international landscape for EMNEs, particularly Chinese MNEs, has shifted remarkedly in recent years. As the world economy is still recovering from the COVID-19 Pandemic, Chinese MNEs are paving new ways to navigate in developed markets as major Western economies are slowing down (IMF, 2023). Chinese MNEs are encountering a unique set of challenges and opportunities as the ‘head wind’, partly generated by geopolitics and ‘de-risking’ in global supply chains, is particularly strong in developed markets. The perplexing situation Chinese MNEs are dealing with in developed markets can be framed as ‘Crisitunity’ due to the tacit and rapidly evolving nature of the external and internal environment (Buchner, 2015). Thus, Chinese MNE internationalization theory focusing on developed markets under the current VUCA environment requires an urgent review (Buckley, 2020).

Chinese MNEs have transitioned from the ‘internationalization phase’ to ‘internationalized phase’ (Luo & Tung, 2018) since 2007. We argue that the springboard perspective may not be sufficient to understand the behaviours and motives of Chinese MNEs’ international expansion in developed markets subsequent to the initial springboarding for two reasons. Firstly, many leading Chinese MNEs such as Huawei, Lenovo, Haier, and Hisense have already advanced their technologies and accumulated valuable international managerial know-how. One of the key motives now for international expansion is to challenge the status quo and overtake their Western peers, thus, fulfilling the aspiration for becoming global reputable brands and industry champions. Secondly, foreign companies with advanced technologies are reluctant to sell their assets to Chinese MNEs or are blocked by their government to do so due to recent geopolitical developments. For instance, a Chinese MNE, Aeonmed Group, proposed to acquire German medical products manufacturer Heyer Medical AG in 2022, but was blocked by the German government. Moreover, there are fewer foreign companies available with strategic assets sought by Chinese MNEs as they advance both technologically and managerially. Thus, the two key internationalization motives of Chinese MNEs that underlined the springboard perspective have changed substantially.

A more nuanced and contextualized approach is thus required to understand the unique challenges facing Chinese MNEs in light of different internationalization phases and market conditions. In this paper, we propose a new ‘surfboard perspective’, for understanding Chinese MNEs’ international expansion in developed markets after their initial entry. We propose that the surfboard perspective addresses and explains the new emerging behaviours of Chinese MNEs during the ‘post-springboard’ expansion stage, thereby complementing the springboard perspective. The surfboard perspective suggests that Chinese MNEs are using international expansion in developed markets as a surfboard not only to actively cultivate capabilities required for sustainable global operation, but more importantly to ascend in global value chains and build their reputable brands in order to compete effectively in the marketplace.

Following the “new context informs new strategy” logic (Shepherd & Rudd, 2014), we first delve into the multifaceted challenges and barriers Chinese MNEs encounter in developed markets during the ‘post-springboard’ expansion. This new and fragmented context sets the scene and provides a rich contextualized underpinning to facilitate the development of the new surfboard perspective. We then argue that the surfboard perspective can potentially fill the void in internationalization theory of Chinese MNEs in developed markets during the ‘post-springboard’ and post-market entry phase.

The Changing Landscape and ‘Western Shock’

The Sino-US rivalry, Ukraine and Russia war, and war in the Middle East have had profound impacts on the international business landscape. The ‘de-risking’ between China and major Western countries is likely to accelerate (Witt, Lewin, Li, & Gaur, 2023). Chinese MNEs are charting new ways to keep up with the latest global competition in light of the VUCA environment and increasing hostility towards them in some Western countries (Witt, 2019).

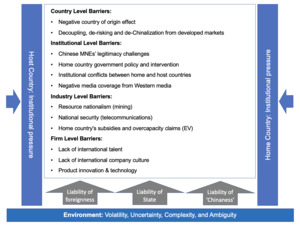

We introduce the term “Western Shock” to encapsulate and illustrate the challenges and negative experiences faced by Chinese MNEs as they contend with various liabilities, differing institutional pressures (both home and host), multi-level barriers, and the underlying VUCA environment during their international expansion into developed markets. Figure 1 illustrates these challenges, barriers, and unpleasant encounters.

Home and host countries’ institutional pressures

Home country institutions are exerting great influence and shaping the business practices of Chinese MNEs. Shifting home country institutional landscapes with tight control at state level and increasing institutional complexity (state, provincial, city, and county levels) have brought a political cloud over Chinese MNEs in developed markets (Su, Kong, & Ciabuschi, 2022). As mentioned before, institutions in host countries have also undergone substantial changes. The changing institutional environment both at the home and in host countries forces Chinese MNEs to navigate policy and regulation uncertainty in order to survive and prosper.

Three types of liabilities

Chinese MNEs face three types of liabilities when competing in the global market:

-

Liability of foreignness (LOF): LOF refers to the additional costs firms experience when operating in host countries (Zaheer, 1995). Chinese MNEs are exposed to LOF derived from the host country’s business environment and latecomer disadvantage compared with the Western counterparts.

-

Liability of state: The Chinese government is often criticized by Western countries for its authoritarian governing approach. According to the survey conducted by the Pew Research Centre (2022), unfavourable views towards China as a state from major developed countries such as the US, Canada, Germany, France, UK, Spain and Sweden, climbed to a historic high in 2021. The Chinese government is perceived as a major threat in some major developed economies thus generating liability of state for Chinese MNEs.

-

Liability of ‘Chinaness’: As suggested by Usunier and Cestre (2007), consumers normally make stereotypical associations between products and countries of origin. Unlike their counterparts in developed markets, Chinese brands are often associated with cheap, low quality and low price products in the West. The liability of ‘Chinaness’ derived from a negative country-of-origin effect during the internationalization process hinders the progress for some Chinese brands in becoming globally reputable brands.

Firm/industry/institutional/country-level barriers

Firstly, at the firm level, Chinese MNEs still lack international talent and inclusive culture. Although progress has been made on the technology and innovation front, Chinese MNEs still need to catch up with their Western peers, especially their incumbent peers in the U.S. Secondly, at the industry level, Chinese MNEs are a heterogeneous group, varying in industry, ownership, and development stage (Lv, Curran, Spigarelli, & Barbieri, 2021). Consequently, MNEs from different industries may encounter different barriers and exhibit different motives during ‘post-springboard’ expansion. For instance, Chinese MNEs (Chinalco, Sinomine) in the natural resources industry may still be driven to cultivate resources and capabilities while dealing with resource nationalism in Western host countries; Chinese MNEs (Huawei, ZTE) in the telecommunications industry may want to ascend global value chains while coping with host countries’ national security scrutiny. Chinese MNEs (BYD, GWM) in the EV industry may intend to build reputable brands and become industry champions while facing the uphill battle of ‘overcapacity’ and state subsidies claims in host countries. Thirdly, at the institutional level, Chinese MNEs’ legitimacy is often challenged in the West due to their affiliation and connection with the Chinese government or Chinese Communist Party (Qiu, 2023). Some Chinese MNEs, especially state-owned enterprises (SOEs), endure constant negative media coverage in developed markets. Fourthly, at the country level, de-Chinalization becomes a distinct feature for some developed economies as geopolitics are fragmented (Bozonelos & Tsagdis, 2023) and de-risking has been high on the political agenda for Western governments in recent years. The new trend of deglobalization has been replaced by de-Chinalization in some Western countries (McElwee, 2023).

In summary, the aforementioned phenomenon described by Western Shock offers an overarching framework to facilitate an understanding of the key composition of the dilemma for Chinese MNEs to operate in developed markets, helping underpin and solicit the surfboard perspective.

The Surfboard Perspective

According to Luo and Tung (2018), IB research on internationalization and Chinese MNEs’ strategy is often complicated due to the tacit nature and complex settings. Given the distinctive difference between developed and developing markets, a typological and categorical approach to viewing developed markets as a cluster during Chinese MNEs’ internationalization process is sensible and can potentially contribute to the theoretical and practical advancement of Chinese MNEs.

Although several generalized theories (Luo & Child, 2015; Luo & Tung, 2007) have been proposed to understand the internationalization process of Chinese MNEs, theories specifically focusing on their internationalization at the ‘post-springboard’ phase still require more probing to fill the research vacuum and answer the practical calls from Chinese MNEs to overcome the key barriers and latecomer disadvantages in developed markets under the current Western Shock context.

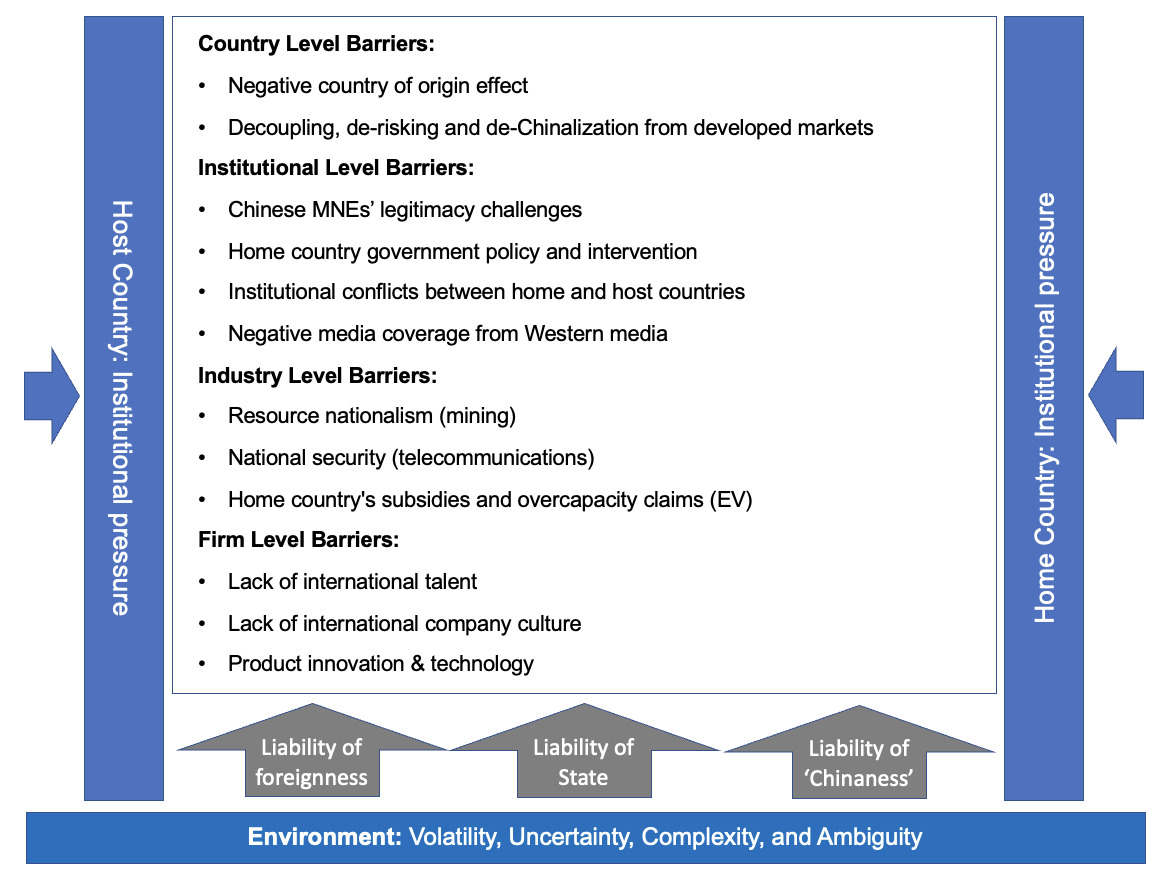

We propose a new theoretical perspective, dubbed ‘surfboard perspective’, which is mainly focused on the ‘post-springboard’ expansion after the initial acquisition stage, and can better capture the motives and behaviours of Chinese MNEs’ internationalization in developed markets. The surfboard perspective (Figure 2) argues that Chinese MNEs use international expansion in developed markets as a surfboard to (1) ascend the global value chains, (2) build reputable brands, and (3) cultivate capabilities. In doing so, Chinese MNEs need to actively upgrade their strategic capabilities and resources as ‘post-springboard’ act to deal with the institutional pressures and market changes, and to overcome all three types of liabilities.

The word of ‘Surfboard’ can be used to better elaborate the behaviours of Chinese MNEs, particularly in the current Western Shock environment. Surfing in the ocean can better portrait the adventurous and tortuous nature of Chinese MNEs’ global expansion. Chinese MNEs need to ‘surf’ in developed markets in order to pursue their brand ambition. Being able to ride and master the waves embodies the dynamic capabilities that are required from Chinese MNEs to operate in a fluid and turbulent international environment.

The Surfboard Perspective: Key Motives

After more than two decades of international expansion since China implemented its ‘going out’ policy in 2001, Chinese MNEs now have higher aspirations as they enter the new ‘post-springboard’ phase although some still have the intension to upgrade their strategic resources and assets as suggested by Luo and Tung (2007, 2018). The surfboard perspective argues that ascending the global value chains, building reputable brands and cultivating capabilities are the major motives for Chinese MNEs’ expansion in developed markets. For example, in recent years pioneering Chinese MNEs in the consumer electronics sector, including Lenovo, Haier, TCL, and Hisense, have conducted extensive international brand-building exercises through sports sponsorships such as F1 (Lenovo), ATP Tour (Haier), FIFA World Cup (Hisense), and NFL in North America (TCL) so as to cultivate global marketing capabilities and lift up the global brand image.

The Surfboard Perspective: Key Behaviours

The strategic behaviours derived from the surfboard perspective can be outlined in five steps: observing, capturing, displacing, mitigating, and enhancing. These behaviours are synchronized with Chinese MNEs’ post-springboard dynamic capabilities building in developed markets (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997), and can be further elaborated as below:

-

Observing

Observing can be denoted as ‘reading waves’. Reading ‘waves’ is the ability to timely anticipate and sense the risks and opportunities in operating in developed markets. Reading waves involves observing the shape, size, speed, and direction of the waves. This action is corelated to Chinese MNEs abilities to properly observe market risks and opportunities in order to make the best strategic decisions as the situation requires. For instance, half a dozen Chinese EV brands, BYD, NIO, Geely, GWM, and Xpeng have entered the European market in recent years after observing the booming market opportunity and favourable home country policy towards developing the EV industry.

-

Capturing

Capturing can be related to ‘selecting the wave’. Capturing the right waves is a critical ability for surfers. For Chinese MNEs, being able to strategize and take calculated steps to expand in developed markets allows them to yield the best commercial results with limited resources. For example, two Chinese MNEs, namely TCL and Changhong, are using the Australian market as a trial market to enhance their global marketing capabilities in order to replicate the branding capabilities and success in other developed markets.

-

Displacing

Displacing can be manifested when ‘dealing with shock waves’. Spatial displacement and movement caused by shock waves are the essential part of a surfing adventure. Skilled surfers are not only able to bounce back, but more importantly ‘bounce forward and upwards’. Chinese MNEs are dealing with different non-market barriers such as geopolitical tensions, trade sanctions and negative home and host country institutional intervention. The geographic and strategic displacement during ‘post-springboard’ internationalization compels Chinese MNEs to maintain a sound geographic market dispersion and cultivate their dynamic capabilities that allow them to strategically reconfigure and reorchestrate resources to deal with the shocks in order to develop readiness, resilience, and relevance in a complex and dynamic environment. For example, the Canadian government ordered three Chinese firms to exit the critical minerals lithium (key ingredient for EV batteries) mining industry in 2022 citing national security concerns. Subsequently, these Chinese firms reconfigured their strategies and redirected resources to Australian market.

-

Mitigating

Mitigating can be achieved through ‘duck diving’ and ‘defusing risk’. Firstly, duck diving allows the surfer to conserve energy and avoid getting caught in the impact zone. This term refers to Chinese MNEs’ ability to continuously perform and innovate while dealing with barriers and three types of liabilities in the Western Shock context. For example, the use of products of the Chinese drone company DJI were prohibited in U.S. government institutions due to the company’s ‘ties with the Chinese military’. However, DJI managed to retain 77% of the U.S. consumer drone market share in 2020. In contrast, no other company has held more than 4% in that particular market. Secondly, managing risk is paramount as surfing can be dangerous. The internationalization of Chinese MNEs in developed markets is also dauting and can be very risky. Chinese MNEs require a contingency plan and the organizational resilience to allow them to defuse the hazard. In the case of an emergency, firms still have the dynamic capabilities and backup plan to survive. For example, the world’s fast-growing Chinese video sharing App, Tiktok, migrated all U.S. user data to servers at the America company Oracle in 2022 to partially defuse U.S. regulatory and national security concerns.

-

Enhancing

Enhancing can be attained with ‘balancing’ and ‘turning’ skills. Firstly, surfers need to maintain a balanced position and posture during challenging conditions to ride the waves effectively. Chinese MNEs need to overcome latecomer disadvantages and build balanced dynamic capabilities (e.g. innovation, technology, branding, international talent) in order to effectively expand in developed markets while dealing with different barriers. A classic example is that of the Chinese EV producer, BYD, which overcame its latecomer disadvantages in developed markets by offering innovative environmental-friendly EVs, combining cutting edge battery technology, sleek design, superior performance, and smart connectivity. By the end of 2023, BYD had caught up with Tesla and held 17% of all global battery EV markets. Secondly, surfers need advanced turning skills to control the speed and direction on the wave. From a strategic manoeuvre standpoint, this implies the strategic agility and adaptability required for dynamic capabilities. Chinese MNEs need to be equipped with sustainable disruptive capabilities that allow firms to quickly learn and adapt to the evolving situation, harness the innovation and technology, and rapidly identify and develop capabilities that compensate for the strategic weakness to deal with emerging competition and non-market barriers. The firm can thus be strategically and favourably positioned to shape future competition and maintain sustainable competitive advantage. For instance, in light of the U.S. trade ban restricting U.S. companies in selling chips and operating systems to Huawei, the latter decisively sold off its low-end phone brand Honor in a move geared toward manoeuvring around U.S. sanctions. Huawei also quickly launched its self-developed HarmonyOS operating system in 2019 to deal with the Android ban from the U.S. government.

Surfing in the ocean can be daunting and requires solid skills, patience, regular practice, and the right mindset. Chinese MNEs’ road to becoming global reputable brands is a bumpy one, and developed markets represent the focal point that allows Chinese MNEs to achieve transformation from a junior to master surfer, and from a ‘cheap option’ to a global reputable brand. Chinese MNEs need to master the skills of international branding, deal effectively with barriers and liabilities, master rhythm and agility, and more importantly, cultivate their dynamic capabilities by observing, capturing, displacing, mitigating, and enhancing.

Conclusion

This paper has contributed to the exiting IB literature by proposing the Western Shock term for international expansion of Chinese MNEs in developed markets, which highlights the environmental challenges and key barriers to Chinese MNEs’ expansion in developed markets and facilitates an understanding of the dilemma in a holistic approach. More importantly, this paper proposes a surfboard perspective of Chinese MNEs’ international expansion in developed markets during the post- springboard phase, which is complementary to the springboard perspective proposed by Luo and Tung (2007, 2018).

Managers of Chinese MNEs, particularly those from SOEs, are undoubtedly exposed to substantial market and non-market barriers in developed markets. The surfboard perspective provides a strategic framework for Chinese MNE managers, enabling them to proactively reorient their thinking, break down their problems into practical steps for navigating these ‘shock waves’, and upgrade capabilities systematically. All these can assist them to better adapt to changing environments and continuously enhance adaptability and agility.

Although this paper primarily focuses on Chinese MNEs, MNEs from other emerging markets could face similar institutional pressures, liabilities of foreignness, and liabilities related to their national state and country-of-origin in developed markets, as indicated by Western Shock. We believe the surfboard perspective can offer valuable insights for MNEs from various emerging markets as they navigate the ‘shock waves’ in developed markets. By adopting the surfboarding approach, managers of EMNEs can more effectively navigate the complexities and uncertainties they face in developed markets, adapt their strategies in response to changing conditions, decompose challenges into manageable components, thereby enhancing their agility, responsiveness, and performance.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the editors’ suggestions and the two anonymous reviewers for their time and effort in reviewing this paper.

About the Authors

Jonson Xia is a senior manager of the Australian subsidiary of a Chinese MNEs in consumer electronics industry and HDR candidate at RMIT University. His research interests focus on Chinese MNEs’ international expansion in developed markets. He has more than 17 years industry working experiences in both China and Australia. His professional skills include sales, marketing, product category management, supply chain, branding, business operations, distribution management, pricing and leadership at the management level.

Xueli Huang is senior lecturer at School of Management at RMIT University in Australia. He has received his PhD from Monash University. Dr Huang’s research focuses on strategic management, international business and innovation management. He has published extensively in leading international journals and two books on Chinese investment in Australia.

Steven Li is a professor at RMIT University in Australia. He has extensive international teaching and consulting experience. Steven’s research interests include Chinese financial markets, corporate finance, financial market efficiency, asset pricing and environmental finance. He has published over 100 academic papers. Steven is active in applying his knowledge and mathematical/statistical modelling skills for solving real world business problems.