Introduction

Understanding the distances between a firm’s home and foreign countries on cultural and institutional dimensions is key to a firm’s internationalization strategy. Managers need to access and process information specific to a foreign country – including on language, culture, religion, education, business and political systems – to form subjective representations of the distance between the foreign and home countries, referred to as psychic distance perceptions (see Ambos, Leicht-Deobald, & Leinemann, 2019; Nebus & Chai, 2014). A failure to do so can lead managers to forego business opportunities and to failed internationalization decisions.

A key challenge is that such psychic distance perceptions are subject to cognitive biases (Nebus & Celo, 2020). Notably, because psychically close countries are more easily understood, they are targeted first to reduce market risks. Yet, by overemphasizing similarities, managers tend to underestimate critical differences. As a result of such psychic overconfidence, managers have to handle unanticipated differences in the internationalization process, which can lead to failures (O’Grady & Lane, 1996). For instance, Australian businesses have focused primarily on Britain as the location for their foreign direct investment, yet have overlooked crucial differences between Australian and British management styles (Fenwick, Edwards, & Buckley, 2003).

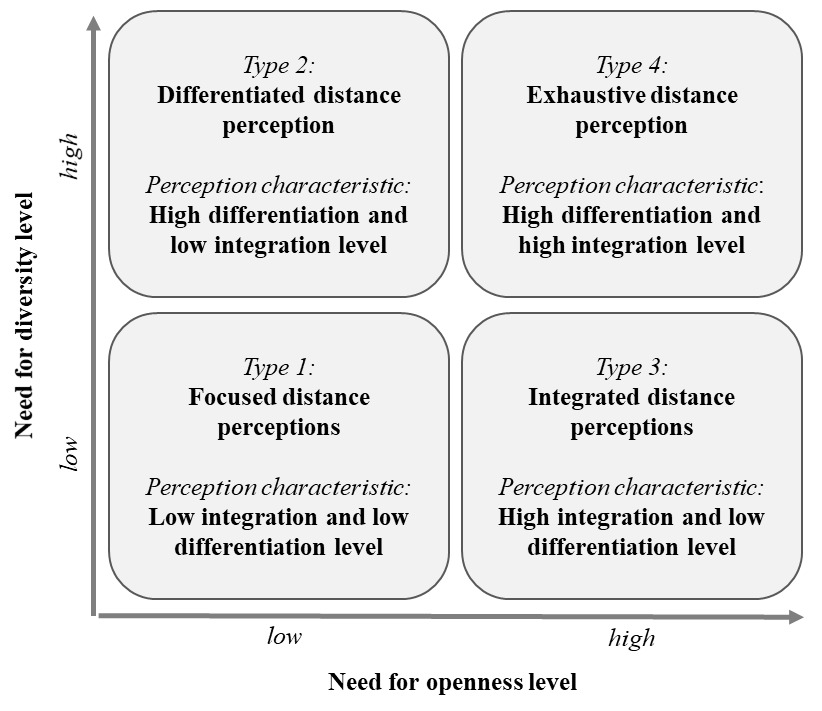

While scholars have investigated into the (social-)psychological aspects of distance perceptions (see Ambos, Leicht-Deobald, & Leinemann, 2019; Håkanson, Ambos, Schuster, & Leicht-Deobald, 2016), we know surprisingly little about the cognitive motivational drivers. Such a focus starts from the premise that because motivation and cognition are deeply intertwined, it may help explain what information on foreign countries managers are motivated to process and how. We develop, first, a managerial typology of four motivated psychic distance perception types (exhaustive, differentiated, integrative, and focused distance perceptions) and their cognitive motivational underpinnings. Second, we elaborate on the fits between these psychic distance types and different internationalization strategies. We offer a framework for managing the psychology of psychic distance perceptions to help ensure a cognition-strategy fit in firms’ internationalization strategy formation.

Unpacking the Psychology of Distance Perceptions in Internationalization Strategies

Managers’ psychic distance perceptions represent conceptual representations of the distance between a firm’s home and foreign countries, based on a number of dimensions (Dow & Karunaratna, 2006). We argue that these perceptions can vary in their differentiation level, referred to here as the number of different country distance dimensions, and in their integration level, i.e., the interrelatedness level among country distance dimensions (Walsh, 1995).

Although different factors may shape such perceptions, the more psychologists study mental processes, the more evidence they find of the roles of two basic cognitive needs in shaping what information we process and how (see Kruglanski & Webster, 1996). The need for openness and the need for diversity (see Reuter & Floyd, 2024) represent the reversals of the need for closure and the need for epistemic authority from the original theory (Kruglanski, 2004).

The need for diversity regulates what information is sought. A high (low) need for diversity refers to the extent to which actors need to seek out information on country distance dimensions without (with) preferred direction. Managers with a low need for diversity may need to access information on countries and distance dimensions that they regard as most authoritative, that confirm the preferred perspective, or that they are particularly familiar with, at the expense of considering a wider variety of different country distance dimensions. For instance, managers may be motivated to attend to countries that share a colonial history, such as Australia and Britain, under the preferred assumption of high historical-cultural similarities, at the expense of a broader range of different country distance dimensions.

The need for openness regulates how actors process information. A high (low) need for openness represents the extent to which actors need to avoid closing on definite information about country differences. They rather spend time and effort integrating disparate, potentially contradictory information. To illustrate, rather than being dissuaded by the uniqueness of Italy’s coffee culture, Starbucks’ first Italian store showcased managers’ motivation to thoughtfully integrate local cultural elements into store design and product offerings. Located in the historic Palazzo delle Poste, the store was crafted to resonate with Milanese culture and aesthetics.

Because they shape what information managers process and how, these two basic needs have the potential to critically shape managers’ psychic distance perceptions. We will, first, propose a typology of four motivated psychic distance perceptions types – exhaustive, differentiated, integrative, and focused distance perceptions – (see Figure 1.) that arise from the interactions between these two cognitive needs.

Second, for each of these psychic distance perception types, we will elaborate on their respective ‘fit’ with a firm’s internationalization strategy and on how managers’ cognitive motivations can be levered when forming a firm’s internationalization strategy (see Figure 2.). This suggests that none of the psychic distance perception types is generally more effective. Their effectiveness depends on their match with the strategies’ informational demands: The psychic distance perceptions’ ‘ecological rationality’ (cf. Kruglanski & Gigerenzer, 2011).

The literature implicitly elaborates on the strategies’ informational demands. It has advanced four internationalization strategy types that vary both along their level of local responsiveness – i.e., the extent to which firms differentiate their offerings to serve particular local market needs, necessitating, as we argue, a high information differentiation level – and along their level of global integration – i.e., the extent to which activities are combined so that they operate using common methods, necessitating, as we argue, a high information integration level. The international strategy (low local responsiveness and low global integration) is an extension of the domestic operations from the home market into foreign target markets (e.g., Moët & Chandon is exported from France). In the multidomestic strategy (high local responsiveness and low global integration), a firm differentiates its offerings according to local market requirements (e.g., Johnson & Johnson’s country-specific strategies). In the global strategy (low local responsiveness and high global integration), a firm applies its strategy across multiple foreign markets, with little adaptation to local needs (e.g., Apple’s global brand and standardized offerings are applied across markets). In the transnational strategy (high local responsiveness and high global integration), a firm applies an overarching strategy while simultaneously adapting to local market requirements (e.g., Blundstone’s global brand identity — durable, high-quality boots — while catering its marketing and distribution strategies to regional preferences, for instance, the boots’ suitability for cold climates in Canada, and fashion appeal in Italy).

Type 1: Focused Distance Perception and International Strategy

First, because a firm’s international strategy is characteristic of a low local responsiveness and low global integration, its informational demands exhibit, we argue, the greatest match with managers’ focused distance perceptions. These managers with a low need for diversity and a low need for openness will most likely be less attentive to a variety of country-specific nuances and cut short their information processing with little integration among different perspectives. They will rather rely on preferred and/or readily-available information on foreign markets, for instance, on cultural, geographic distance and exchange rate information, to assess the risks in entry mode decisions (see Grosse & Trevino, 1996). Moreover, they will maintain a preferred domestic focus in their competitive strategy. For instance, with Harley Davidson’s international strategy into Japan in the 1980s, its managers did not need the cognitive motivation to process information on how to adapt their motorcycles to local tastes or engineering standards; instead, they sold the American design, look and sound abroad. Similarly, managers at Rolex, the Swiss watchmaker, need the cognitive motivation to focus on a standardized product line and marketing approach that offers the same watches, leverages the prestigious global brand reputation and economies of scale with minimal regional adaptation.

Type 2: Differentiated Distance Perception and Multidomestic Strategy

Second, because a firm’s multidomestic strategy is characteristic of high local responsiveness and low global integration, its informational demands exhibit, we argue, the greatest match with managers’ differentiated distance perceptions. These managers with a high need for diversity and a low need for openness will most likely access and process information across diverse country-specific sources to form a differentiated understanding of the specific local market risks and local requirements for their competitive positioning. Consider Playbox managers’ cognitive motivation necessary to assess foreign market risks on a range of cultural, administrative, geographic and economic distance dimensions and to form the firm’s multidomestic strategy emphasizing highly specialized offerings that are highly responsive to regional nuances, meet local customers’ preferences, yet, with little further overarching integration. Accordingly, toy design is based on local mythology, culture, trends, safety standards and by effectively connecting with children and parents.

Type 3: Integrative Distance Perception and Global Strategy

Third, because a firm’s global strategy is characteristic of low local responsiveness and high global integration, its informational demands exhibit, we argue, the greatest match with managers’ integrative distance perceptions. These managers, with their low need for diversity, are unlikely to search for information across diverse country-specific sources; instead, they focus on preferred sources (e.g., on customers primarily). Yet a high need for openness will drive these managers to integrate the available information into an overarching corporate strategy concept, for instance, of standardized offerings that are scalable across foreign markets with little local responsiveness (i.e., one brand, one suite of products, one message from corporate headquarters, and supply chain optimization). Consider Spotify’s managers’ cognitive motivation to form the firm’s global strategy with its personalized approach to individual users based on their preferences that emphasizes integration at the corporate level over local market differentiation. Also, Innocent Drinks, a UK-based juice company, expanded its product line in France by introducing Gazpacho, a chilled vegetable soup, that was later launched in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, demonstrating the strong connections rather than differences between markets.

Type 4: Exhaustive Distance Perception and Transnational Strategy

Fourth, because a firm’s transnational strategy is characteristic of high local responsiveness and high global integration, its informational demands exhibit, we argue, the greatest match with managers’ exhaustive distance perceptions. A high need for diversity will drive these managers to access and process information across diverse, local country-specific sources to form differentiated understandings of possible risks along multiple country distance dimensions and to optimize their competitive strategy for the local specificities in line with that strategy’s high level of local responsiveness. A high need for openness will drive these managers to integrate these local specificities into an overarching strategy that provides a cohesive structure in line with headquarters’ priorities. Consider Walmart’s managers’ cognitive motivation necessary to form the firm’s strategy of providing customized offerings to diverse local markets, while simultaneously levering its group-level purchasing power and efficiencies in the international supply chain. Also, Ben & Jerry’s, the Vermont-based ice cream manufacturer, localizes flavors (e.g., Green Tea and Azuki Bean in Japan, Fairly Nuts in the UK) and marketing to regional preferences (e.g., local social media accounts, local community initiatives), while maintaining its core global brand identity – focused on high-quality, socially conscious products.

In sum, because managers’ distance perceptions need to fit the internationalization strategy pursued, it is crucial to develop disciplined approaches to these mental processes.

Managing the Psychology of Distance: How to Create a Cognition–Strategy Fit

All mental processes are hard to manage. They are neither visible, nor tangible. They are highly motivated. To effectively manage the cognitive motivational psychology of distance perceptions in organizations, we have derived three actionable recommendations:

-

Manager (self-)awareness training: Make people understand their need for diversity and their need for openness levels to calibrate perceptions. People may not be aware of how they process information until they have evidence. Once they have evidence, it may provoke formative change. To provide evidence, one can administer (self-)assessment surveys that help showcase which information sources managers are motivated to access and how openly they process it. For the first, beyond assessing the diversity of sources used, one can also assess the degree to which they have a determinative influence on the acquisition of knowledge or their degree of epistemic authority, for instance, by using the Epistemic Authority Scale or an adapted version of the Hierarchy of Epistemic Authorities Test (Kruglanski et al., 2005). For the second, one can use the Need for Closure Scale (Kruglanski, Webster, & Klem, 1993). Leaders may establish feedback loops ranging from real performance data in foreign markets to perception audits and benchmarking in focus groups to ensure perceptions align with strategies.

-

Manager development pathways: Align people’s need for diversity and their need for openness levels with strategic goals. Although people have ingrained cognitive motivations that shape how they access and process information, such cognitive motivations can also be cultivated to build the needed traits that align with strategic goals. Organizations may embrace development pathways by focusing on interventions, such as access to diverse country-specific information sources, cross-cultural learning systems, international job secondments or rotations, country visits, internationally-diverse teams, dual-lens decision frameworks, time pressure, etc., that can induce lasting shifts in people’s cognitive motivations.

-

Manager selection: Assign people with the ‘right’ cognitive motivation to form the firm’s internationalization strategy. The same instruments can be used to assess managers’ cognitive motivations and to lever them when assigning managers’ roles in the pursuit of the firm’s internationalization strategy. While, in general, managers with high needs for diversity and openness may help overcome oversimplification tendencies and key biases, such as the confirmation bias or the mere exposure effect, this profile may also come at a downside for those internationalization strategies that necessitate more focused rather than exhaustive distance perceptions. It could create an ‘analysis paralysis’ syndrome overemphasizing local differences and preventing firms from pursuing a course of action. This may be particularly problematic in smaller firms that seek more expedient internationalization. Although the typology may be generalizable, there may be notable boundary conditions. We also anticipate that technology companies with standardized global products may benefit most from an integrative or focused perception, whereas retail firms expanding into culturally distinct markets (e.g., food service) may benefit most from differentiated or exhaustive perceptions. The effectiveness of each profile depends on the match with the informational demands of the internationalization strategy at stake: its ‘ecological rationality’ (cf. Kruglanski & Gigerenzer, 2011).

Conclusion

In sum, firms are strongly advised to embed perception management in their processes to ensure a cognition-strategy fit when they form their internationalization strategies. It is not only what information managers have access to but also how they approach it that shapes their understandings of the distance between a firm’s home and foreign countries – their psychic distance perception. By drawing on motivated cognition insights, we have developed a managerial typology of four motivated psychic distance types and their cognitive motivational underpinnings. We have also elaborated on their likely fits with four distinct company internationalization strategies. While the literature has started to illuminate the (social) psychology of managers’ distance perceptions, we contribute the key role of cognitive motivation. Future research may further unpack their interactions with other team members’ cognitive motivations and/or with other organizational factors to further illuminate the psychology of distance. Finally, we provide actionable recommendations for managing managers’ cognitive motivations in internationalization strategies.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for thoughtful guidance throughout the review process. This research has benefitted from funding by the Movetia (Projet 2023-1-CH01-IP-0057). The author bears sole responsibility for the article.

About the Author

Emmanuelle Reuter (Dr. oec. HSG) is a professor of innovation management, and Director of the Master of Science in Innovation at the University of Neuchâtel, Institute of Management, Switzerland. She received her PhD in management from the University of St. Gallen. Her research focuses on innovation, (strategic) change, governance, business and regulation. She has authored publications that appeared in outlets, such as: Administrative Science Quarterly, Business, Strategy and the Environment, Organization & Environment, the Journal of Business Research, and the Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal.